Like malaria, dengue fever is an infectious disease transmitted by mosquitoes. Unlike malaria, there is no vaccine for it. As many as 100 million people contract dengue each year, but MSU researcher Zhiyong Xi is working to change that.

Among the estimated 2.5 billion people at risk for dengue, more than 70 percent live in Asia Pacific countries, which spurred Xi to establish a collaborative research institute at Sun Yat-sen University in Guangzhou, China.

There, Xi and his colleagues have made a promising breakthrough. They’ve determined that the Wolbachia bacterium can stop the dengue virus from replicating in the mosquitoes that are the primary transmitters of the disease.

Once the researchers pinpoint the mechanisms responsible for interrupting virus replication, they’ll be able to improve the efficiency of the interference—a critical step in breaking the fever.

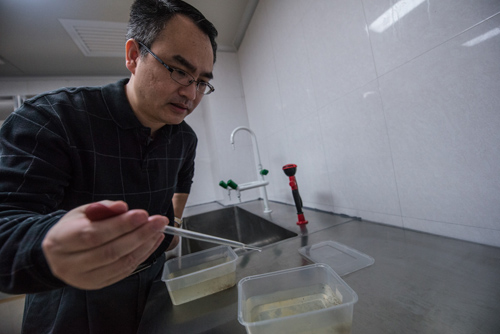

Researcher profile: Zhiyong Xi

Zhiyong Xi is an assistant professor in the Department of Microbiology and Molecular Genetics.

For most people in the United States, the mosquito is no more than an annoying summer pest that causes a few itchy bumps. But for a large portion of the world, mosquitoes carry dengue fever—a painful disease with no cure and no vaccine.

Though rare in the continental United States, Hawaii was the site of a dengue epidemic in 2001, and there have been cases in Florida. Overall, about one-third of the world’s population is at risk of contracting dengue fever and up to 100 million people are infected each year. While most people recover in about two weeks, the infection can turn into dengue hemorrhagic fever, which causes bleeding from the nose and gums and can be fatal.

Thanks to Zhiyong Xi’s work with mosquitoes and Wolbachia bacteria, researchers are closer than ever to eradicating this devastating disease.

“My long-term goal is to develop control strategies to block dengue virus transmission in mosquitoes,” says Xi, assistant professor of microbiology and molecular genetics and director of the Sun Yat-sen University–Michigan State University Joint Center of Vector Control for Tropical Diseases. “In nature, about 28 percent of mosquito species harbor Wolbachia bacteria, but the mosquitoes that are the primary transmitters of dengue have no Wolbachia in them. We found that Wolbachia is able to stop the dengue virus from replicating. If there is no virus in the mosquito, it can’t spread to people, so disease transmission can be blocked.”

Xi began his scientific career by earning a degree in pharmaceuticals, but changed his focus when he began a graduate degree.

“When I started my master’s, I changed my focus to this project as it is a very important problem to address,” he says.

He continued this focus during his postdoctoral work at Johns Hopkins.

“I have been working on this a long time,” he says. “In China, there is a long tradition of studying this disease.”

As the director of the Joint Center, Xi is encouraged about the future and solving this challenging problem. His work could have widespread effects around the world. Solving the problem at the transmission stage is a sustainable solution that would help all affected regions.

“For poor countries, even those who can’t afford drugs will be helped,” he says. “This will help all people. You do not have to be rich and get a vaccine or a drug. Everyone will benefit.”

When asked how he would feel if his research was responsible for wiping out dengue fever, a large smile breaks out on his face.

“That would be a dream,” he says. “It is a dream for me and for all scientists. It is not about talking with each other in the lab or an office. It is all about helping people all over the world.”

*Source: Michigan State University