With the 2015 sesquicentennial of Abraham Lincoln’s death approaching, interest is rising, and with new tools, UA researchers have turned their attention to one of the last remaining mysteries about what reportedly was the largest traditional funeral in American history – the train’s color.

A trove of information exists about Abraham Lincoln’s funeral, which drew millions of mourners during a two-week railway procession across the Northern states.

But until now, the precise color of the president’s railcar had been lost to history.

With the 2015 sesquicentennial of Lincoln’s death approaching, interest is rising, and with new tools, researchers at the University of Arizona have turned their attention to one of the last remaining mysteries about what was “perhaps the largest traditional funeral in American history,” says Wayne Wesolowski.

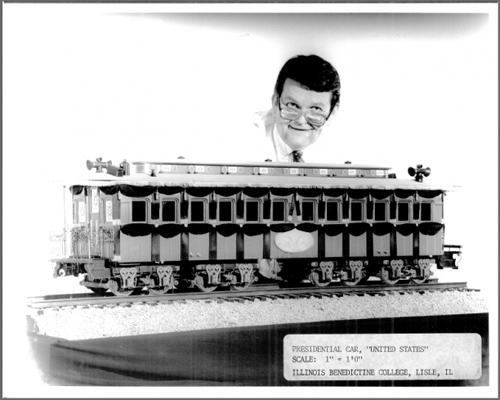

Wesolowski, a chemist and model train maker, was director of the Lincoln Train Project at Benedictine University near Chicago for 10 years. In 1995, he completed a years-long project of building a scale model of Lincoln’s car, the locomotive and hearse and horses, all together measuring nearly 15 feet in length.

After 30 years as a chemistry professor at Benedictine, Wesolowski retired to Tucson, and continues to teach as a chemistry lecturer at the UA.

A Chicago group known as the Lincoln Funeral Car Project approached Wesolowski to consult on their efforts to build a full-size version of Lincoln’s funeral car, intending to trace as closely as possible the funeral route for the 150th anniversary. An obvious question: what color to paint the new replica?

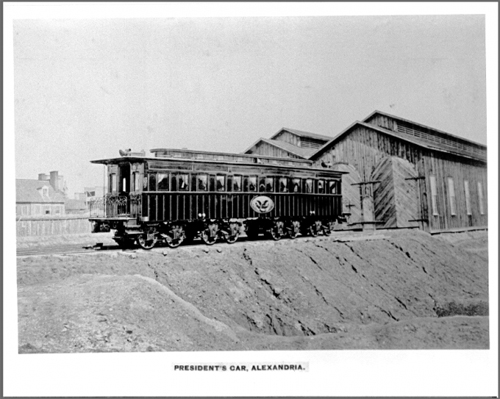

However, no color photographs, no color lithographs and no contemporary color paintings exist of Lincoln’s private car, named “The United States.” Newspaper accounts from the time describe the color as both “rich chocolate brown” and “claret red.” But “chocolate” in 1865 was strictly a drink, very different from the milk chocolate we know today, so the two descriptions are compatible.

The car burned in a fire in 1911, having been sold at auction to Union Pacific after the funeral and passing through several private hands afterward. Just one artifact of exterior wood survived, and after years of searching, Wesolowski acquired a pencil sized piece of trim.

Using three separate labs at the UA – in chemistry/biochemistry (Brook Beam, Keck Imaging Center), art (Karen Zimmermann, Jack Sinclair Letterpress Studio) and the Arizona State Museum – Wesolowski set about investigating for the true color.

And with the help of Nancy Odegaard, conservator and head of the preservation division, comparing layers of microscopic paint chips from the original car to national color standards, Wesolowski at last found the true original color, which he describes as a dark maroon, darker, but not too far off of what he’d painted his model.

The effort at historical exactness reflects on how deeply the country mourned Lincoln’s death. In early 1865, the United States Military Railroad delivered Lincoln a private railroad car for presidential use. But Lincoln never used the car alive. His presidential funeral procession left Washington on April 21, 1865, closely retracing the route Lincoln traveled as president-elect in 1861, bypassing cities with a large number of Southern sympathizers.

“It was a procession of mourning and without TV or radio, the only way to participate was to leave the farm, close the store and come trackside,” Wesolowski says. “Just being there was so important. It was a colossal event.”

Millions of Americans – an estimated one-third of the Northern population – came in person to see the funeral. In New York and Chicago, the crowds topped a half-million. In the countryside, people lined the tracks just to glimpse the train as it passed, similar to the Robert Kennedy funeral train.

“It was a political event. It was a social event. It was a catharsis. The man who said in victory, ‘Malice toward none,’ was dead,” Wesolowski says. “There is now a chance to re-create a little of that history.”

Wayne Wesolowski with his 1/12 miniature car. What color should it be? (Image credit: Benedictine University Library)

– By Eric Swedlund

*Source: The University of Arizona