Rodents may have taken over seed-dispersal role of now-extinct mammals

Big seeds produced by tropical trees such as black palms were probably once ingested and then left whole by huge mammals called gomphotheres.

Gomphotheres weighed more than a ton and dispersed the seeds over large distances.

But these Neotropical creatures disappeared more than 10,000 years ago. So why aren’t large-seeded plants also extinct?

A paper published this week in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) suggests that rodents may have taken over the seed-dispersal role of gomphotheres.

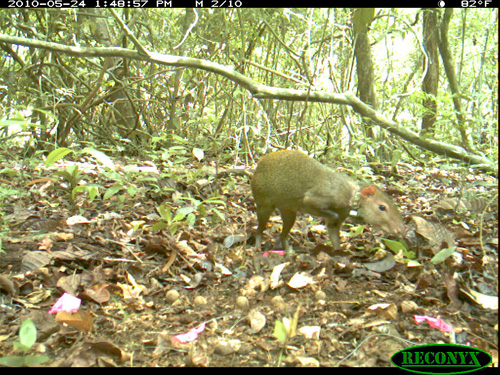

A camera-trap caught this agouti in the act of stealing seeds from another's cache. Image credit: B.T. Hirsch

“The question has been: how did a tree like the black palm manage to survive for 10,000 years, if its seed-dispersers are extinct?” asks Roland Kays, co-author of the paper and a zoologist at North Carolina State University and the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences.

“This research solves a long standing puzzle in ecology,” says Alan Tessier, program director in the National Science Foundation’s (NSF) Division of Environmental Biology, which funded the research.

“How did plant species that seem to be dependent on Pleistocene megafauna for seed-dispersal survive the extinction of that megafauna?”

Now, says Kays, scientists may have an answer.

Camera-traps were placed at caches to determine which animals moved tropical tree seeds. Image credit: B.T. Hirsch

By attaching tiny radio transmitters to more than 400 seeds, Patrick Jansen, a scientist at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI) and Wageningen University and colleagues found that 85 percent of the seeds were buried in caches by agoutis, common rodents in tropical lowlands.

Agoutis carry seeds around in their mouths and bury them for times when food is scarce.

Radio-tracking revealed a surprising finding: when the rodents dig up the seeds, they usually don’t eat them, but instead move them to a new site and bury them, often many times.

One seed in the study was moved 36 times.

Miniature transmitters, attached to seeds with an antenna, tracked dispersal by agoutis. Image credit: B.T. Hirsch

Researchers used remote cameras to catch the animals digging up cached seeds. They discovered that frequent seed movement primarily was caused by animals stealing seeds from one another.

Ultimately, 35 percent of the seeds ended up more than 100 meters from their origin. “Agoutis moved seeds at a scale that none of us had ever imagined,” says Jansen.

“We had observed seeds being moved and buried up to five times, but in this system it seems that re-caching behavior is ‘on steroids,'” says Ben Hirsch of STRI and Ohio State University.

Rodents warned scientists of seed movement by pulling the transmitter off a magnet. Image credit: Patricia Kernan

“By radio-tagging the seeds, we were able to track them as they were moved by agoutis, find out if they were taken up into trees by squirrels, then discover the seeds inside spiny rat burrows.

“That allowed us to gain a much better understanding of how each rodent species affects seed dispersal and survival.”

By taking over the role of Pleistocene mammals in dispersing large seeds, thieving, scatter-hoarding agoutis may have saved several species of trees from extinction.

Radio-collars allowed researchers to follow agoutis across tropical forests in Panama. Image credit: Christian Ziegler

Other co-authors of the paper are Willem-Jan Emsens of Wageningen University and the University of Antwerp; Veronica Zamora-Gutierrez of Wageningen University and the University of Cambridge; and Martin Wikelski of STRI and the Max Planck Institute for Ornithology, as well as the University of Konstanz.

Black palm seeds, once sown by extinct megafauna, are now sown by agoutis. Image credit: Christian Ziegler

*Source: National Science Foundation (NSF)