AUSTIN, Texas — Scientists at the University of Texas at Austin’s Institute for Geophysics helped develop a blueprint for a possible future NASA lander mission to Europa, an icy moon of Jupiter that has a global ocean covered by an ice shell. Europa’s large reservoir of liquid water has long enchanted planetary scientists with the possibility of harboring life. Many experts believe it to be the most likely place in our solar system besides Earth to host life today. The proposed mission is designed to assess the moon’s habitability by studying its surface composition, ice shell, ocean and geology.

Don Blankenship, senior research scientist at the institute, is part of the science definition team commissioned by NASA to draft the report, which appears in the August 2013 issue of Astrobiology. Blankenship and two colleagues — Krista Soderlund, postdoctoral fellow at the institute; and Britney Schmidt, formerly a postdoctoral fellow at the institute, now assistant professor at the Georgia Institute of Technology — developed a part of the mission scenario that would use sound waves to study the moon’s icy shell, deep ocean and possible shallow lakes.

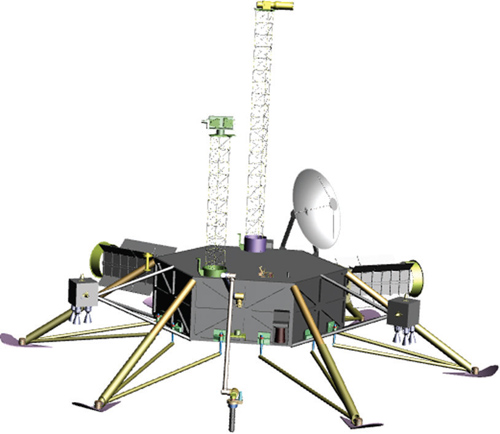

Depiction of the model Europa lander implementation. Descriptions of the model payload are provided in the 2012 NASA lander study (Image credit: Europa Study Team, 2012).

The Texas team has long been at the forefront of developing the capacity to explore Europa. Blankenship is part of a team developing NASA’s Europa Clipper mission concept, which would conduct remote reconnaissance of the moon and help identify possible landing sites for a subsequent Europa lander mission such as the one outlined in this latest study. Blankenship and Schmidt are building an autonomous underwater robot with engineers at Austin-based Stone Aerospace as a prototype for a cryobot that could one day explore Europa’s ocean or lakes. They plan to test it under an ice shelf in Antarctica in 2015.

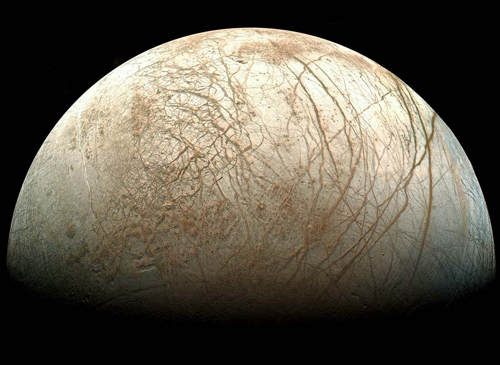

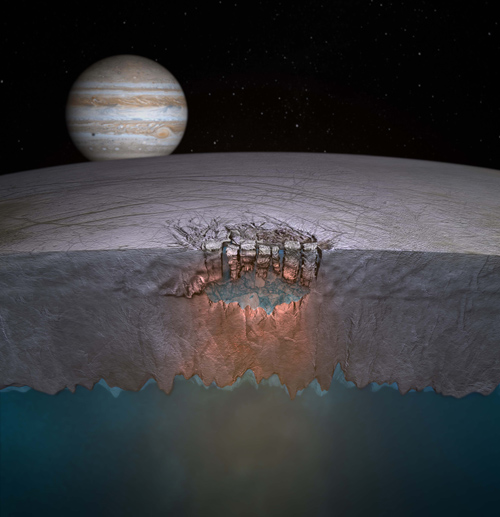

The Texas team has also used existing data to expand our understanding of the Jovian moon. Using imagery from the Galileo mission, Schmidt and Blankenship found evidence for large lakes of water embedded near the surface of Europa’s ice shell, which might provide a habitat for life. The discovery re-energized scientists searching for life on Europa.

Europa, as viewed from NASA’s Galileo spacecraft. Visible are plains of bright ice, cracks that run to the horizon, and dark patches that likely contain both ice and dirt. Image reprocessed by Ted Stryk.

As envisioned in this latest report, a Europa lander would have a series of seismometers embedded in its six legs, allowing mission scientists to measure the thickness of the moon’s all-encompassing ice shell, study the flexing and cracking of the ice in response to tidal forces, model the exchange of chemicals between the moon’s surface and the deep ocean and potentially confirm the existence of lakes embedded in the ice shell. This information would help scientists determine where the best habitats for life might exist within the moon.

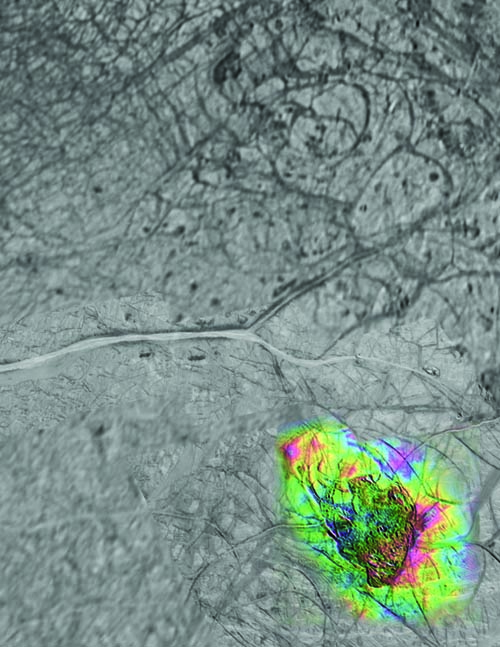

Another prominent part of the Europa lander concept is focused on the chemical composition of the top few inches of ice at the surface. The lander design includes a drill for collecting subsurface samples and spectrometers to analyze chemical compositions. Some of the questions to be addressed include: What makes up the reddish “freckles” and reddish cracks that stain the icy surface? What kind of chemistry is occurring there? Are there organic molecules, which are among the building blocks of life?

Europa’s “Great Lake” discovered in 2011. Scientists speculate many more exist throughout the shallow regions of the moon’s icy shell. Credit: Britney Schmidt/Dead Pixel VFX/Univ. of Texas at Austin.

Blankenship, Soderlund and Schmidt were part of a 22-person team preparing the report.

“If one day humans send a robotic lander to the surface of Europa, we need to know what to look for and what tools it should carry,” said Robert Pappalardo, the study’s lead author, based at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, Calif. “There is still a lot of preparation that is needed before we could land on Europa, but studies like these will help us to focus on the technologies required to get us there, and on the data needed to help us scout out possible landing locations.”

Thera Macula (false color) is a region of likely active chaos production above a large liquid water lake in the icy shell of Europa. Color indicates topographic heights relative to background terrain. Purples and reds indicate the highest terrain. Credit: Paul Schenk/NASA

This work was conducted with Europa study funds from NASA’s Science Mission Directorate, Washington. JPL is a division of the California Institute of Technology, Pasadena.

*Source: The University of Texas at Austin