It is well known that the human body has a highly developed immune system to detect and destroy invading pathogens and tumor cells. Now, researchers at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) have shown that the body has a second line of defense against cancer – healthy cells. A new study shows that normal mammary epithelial cells, as they are developing, secrete interleukin 25, a protein known for its role in the immune system’s response to inflammation, for the express purpose of killing nearby breast cancer cells.

“We found that normal breast cells provide an innate defense mechanism against cancer by producing interleukin 25 (IL25) to actively and specifically kill breast cancer cells,” says breast cancer authority Mina Bissell, of Berkeley Lab’s Life Sciences Division, who led this research. “This suggests that IL25 receptor signaling may provide a new therapeutic target for the treatment of breast cancer.”

The results of this research are reported in the journal Science Translational Medicine in a paper titled “IL25 Causes Apoptosis of IL25R-expressing Breast Cancer Cells Without Toxicity to Nonmalignant Cells.” Co-authoring the paper with Bissell were Saori Furuta, Yung-Ming Jeng, Longen Zhou, Lan Huang, Irene Kuhn and Wen-Hwa Lee, of the University of California, Irvine, who along with Bissell is a corresponding author.

Although cancer remains a leading cause of premature death in the world today, most people live cancer-free lives for decades. In fact, the rate of cancer disease in the human population is surprisingly low given that the cells in our bodies are exposed on a daily basis throughout our lifetimes to radiation and chemical damage, plus a host of other factors that promote harmful DNA mutations and malignant tumors. It is not as if mutant cells are not being generated, explains Saori Furuta, lead author of the Science Translational Medicine paper and a Berkeley Lab colleague of Bissell’s.

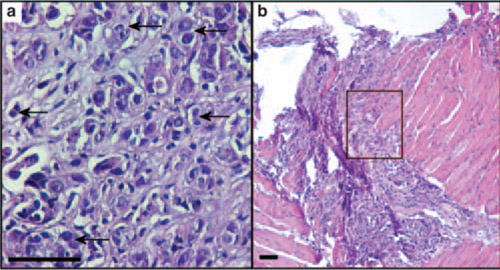

Stained sections of (a) control and (b) IL-25–treated tumors with higher-magnification image of the boxed region in (b). Control sample shows actively growing tumor cells (arrows), whereas in the IL-25–treated sample, the tumor was completely regressed. Image courtesy of Saori Furuta

“Even healthy individuals produce genetically impaired cells at the rate of up to 1,000 aberrant cells per day, however, as a part of homeostatic regulations, these cancer-prone cells are efficiently eradicated by the so- called tumor surveillance system of our body,” Furuta says. “A number of tumor surveillance mechanisms have been described in the past, including the classic molecular tumor suppressors, immune surveillance, and suppression by the extracellular matrix and other microenvironmental factors. We are now adding a new type of tumor suppression to this list, IL25 and other proteins secreted by normal breast cells that kill or subdue their mutated neighbors.”

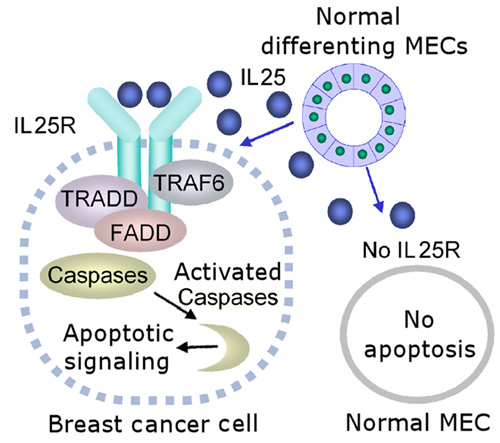

In their study, Furuta, Bissell, Lee and their colleagues found that whereas IL25 was highly toxic to breast cancer cells, it did not harm normal breast cells. The selectivity, they discovered, is due to the presence of an abundance of exposed IL25 receptors on breast cancer cells. These IL25 receptors were absent on normal breast cells.

“Since IL25 is produced by healthy breast tissue as a natural defense mechanism against cancer during the cell differentiation process, we should be able to utilize IL25/IL25 receptor signaling as an organic approach to breast cancer therapy,” Furuta says.

Saori Furuta in the research group of Mina Bissell found that normal breast cells, secrete the protein interleukin 25 to kill nearby breast cancer cells. Photo by Roy Kaltschmidt, Berkeley Lab Public Affairs

Normal epithelial cells, in cooperation with the microenvironment that surrounds them, actively help maintain the health and integrity of tissue. They do this in part by regulating the secretion of cell signaling factors – both autocrine and paracrine – that promote the development of healthy organs and prevent the aberrant growth of neighboring cells. In previous studies, Furuta and collaborators have shown that conditioned-medium, taken from normal mammary epithelial cells while in the process of forming acini in a 3D lamin-rich extracellular matrix culture, can “revert” the malignant phenotype of breast cancer cells so that they behave as if they were normal breast cells. Similar results were also achieved with certain cell signaling inhibitors.

Says Bissell, “These observation suggested that acinus-forming nonmalignant mammary epithelial cells secrete factors that can suppress the phenotype of breast cancer cells growing in 3D cultures. We hypothesized that such a complex phenotypical reversion is likely the result of multiple signaling factors that in combination allow cancer cells to form quiescent acinar-like structures. We sought to identify and characterize these factors using solubility and size-fractionation of the conditioned medium from normal mammary epithelial cells, along with functional assays to identify the active molecules.”

This schematic shows the cytotoxicity of IL25 on breast cancer cells that express IL25 receptor (IL25R). Nonmalignant mammary epithelial cells (MECs) do not express IL25R and are resistant to apoptosis induced by IL25, whereas cancer cells that express IL25R are susceptible to IL25–induced apoptosis. Image courtesy of Saori Furuta

Fractionating the conditioned medium first by solubility revealed that its tumor suppressive activity could be divided into a morphogenic insoluble fraction and a cytotoxic soluble fraction. Fractionating this cytotoxic soluble portion according to molecule size revealed that the most potent tumor cell–killing activity took place in the 10-to 50-kiloDalton range, which would be something the size of a protein. Mass spectrometry was then used to identify the cytokine IL25 as the protein with the most potent cytotoxic activity. Subsequent functional assays revealed that IL25 interacts with the IL25 receptor to activate apoptosis (cell death).

“We analyzed randomized cohorts of breast biopsy samples and found that 20-percent of the breast cancer samples tested were IL25 receptor-positive,” Furuta says. “Importantly, these IL25 receptor-positive tumors were highly invasive and correlated to poor clinical outcome patients. We believe that in the future the IL25 receptor will serve as a novel therapeutic marker for breast cancer diagnosis and treatment.”

Furuta says she and Bissell and their colleagues are now looking at five other proteins they discovered being secreted by normal developing breast cells. While these other proteins are cytostatic rather than cytotoxic, meaning they stop the growth of cancer cells rather than kill the cells, Furuta says she and her colleagues are investigating whether combinations of these other proteins with IL25 could prove to be an effective therapy against some forms of especially aggressive breast and other cancers.

This work was primarily supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health’s National Cancer Institute.

– By Lynn Yarris

*Source: Berkeley Lab