For 30 years, two General Electric facilities released about 1.3 million pounds of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) into New York’s Hudson River, devastating and contaminating fish populations. Some 50 years later, one type of fish—the Atlantic tomcod—has not only survived but appears to be thriving in the hostile Hudson environment.

Researchers from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) have joined colleagues from New York University (NYU) and NOAA to investigate this phenomenon and report that the tomcod living in the Hudson River have undergone a rapid evolutionary change in developing a genetic resistance to PCBs.

Although this kind of reaction has been seen when insects develop resistance to certain insecticides, and bacteria to antibiotics, “This is really the first demonstration of a mechanism of resistance in any vertebrate population,” said Isaac Wirgin of NYU’s Department of Environmental Medicine and leader of the study. Moreover, he said, the team has found that “a single genetic receptor has made this quick evolutionary change possible.”

The findings, reported online in the Feb. 17 issue of Science, provide a first look at “natural selection going on over a relatively short time, changing the characteristics of a population,” said WHOI Senior Scientist Mark E. Hahn, who, together with WHOI biologist Diana Franks, collaborated with Wirgin on the study. “It’s an example of how human activities can drive evolution by introducing stress factors into the environment.”

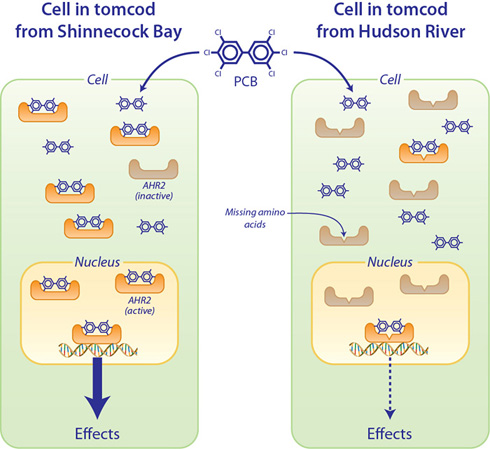

Tomcod from the Hudson River have a variant protein that makes them less sensitive to the toxic effects of PCBs. The effects of PCBs occur through their interaction with a protein called Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor 2 (AHR2). AHR2 is normally inactive, but when PCB molecules bind to it, AHR2 becomes activated and acts as a molecular switch to turn on other genes that lead to toxicity (“Effects” in the figure). Tomcod such as those from Shinnecock Bay, Long Island, NY (left panel) have a normal version of the AHR2 protein, which has a high affinity for PCBs. Tomcod from the Hudson River (right panel) have a variant AHR2 protein that is missing two amino acids (building blocks of proteins). Without these two amino acids, the AHR2 from Hudson River fish has a reduced ability to bind PCBs as compared to the normal AHR2 protein. This makes the Hudson River fish less sensitive to the effects of PCBs. (Illustration by Jack Cook, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Looking at the ability of the fish to respond to the contaminants, the researchers found the primary changes occurred in a receptor gene called AHR2, which is important in mediating toxicity in early life stages and can control sensitivity to PCBs. In his work over the last 16 years in the Acushnet River Estuary near New Bedford, Mass., biologist Hahn has found the same gene involved in controlling other fishes’ responses to PCBs.

The AHR2 proteins in the Hudson Rover tomcod, he said, appear to be missing two of the 1,104 amino acids normally found in this protein. This causes the receptor to bind more weakly with PCBs than normal, suggesting a reason why the contaminant does not affect the tomcod in this location as much as it does tomcod in other locations. The Hudson River tomcod “are not as sensitive to PCBs,” Hahn said. “The mechanism by which PCBs cause toxicity is dampened in this population.”

The difference between AHR2 proteins in tomcod from Hudson River (right panel) and Shinnecock Bay (left panel) is the loss of two amino acids out of the 1,104 amino acids that normally make up the AHR protein. (Illustration by Jack Cook, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

While this may be good news for the tomcod, it may bode not so well for their predators, and even humans. “The tomcod survive but they still accumulate PCBs in their bodies and pass it on to whatever eats them,” Hahn said.

Wirgin noted that tomcod spawn in the winter, and in the summer become “a major component of the diets of striped bass and other fish.” This can lead to “an abnormal transfer of contaminants up the food chain,” perhaps all the way to humans who may consume them.

In addition, the tomcod’s genetic changes “could make them more sensitive to other things,” and affect their ability to break down certain other harmful chemicals, such as PAHs (polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons), Hahn said. “So it’s conceivable that the Hudson River tomcod could be more susceptible to PAHs because it cannot degrade them properly,” he said.

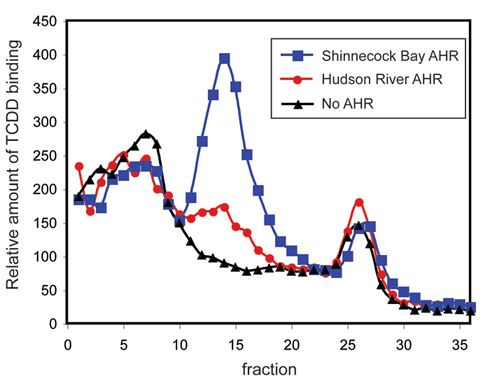

This figure illustrates results of an experiment to compare the ability of the AHR2 proteins from Hudson River tomcod (variant AHR2 missing two amino acids) and Shinnecock Bay tomcod (normal AHR2) to bind TCDD (dioxin, a surrogate for PCB). The peaks in the middle represent binding of dioxin to each AHR2. The results show that AHR2 from Hudson River fish has a reduced ability to bind dioxin as compared to the wild-type AHR2. The impaired ability of AHR2 from Hudson River tomcod to interact with chemicals like dioxin or PCB explains the reduced sensitivity of these fish to PCBs in their environment. (Diana Franks and Mark Hahn, Wood Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Also, he added, these receptors are involved in normal development, and a genetic change could lead to a change in a fish’s health. “There could be evolutionary costs,” Hahn said. “We don’t know yet what they are but it’s something that needs to be considered.”

“Hudson River tomcod have experienced rapid evolutionary change in the 50 to 100 years since release of these contaminants,” the researchers say in their paper. Added Wirgin: “Any evolutionary change at this pace is not a good thing.”

Ironically the recently begun EPA-mandated cleanup of Hudson River PCBs could be trouble for the tomcod. If there are evolutionary costs to having the variant AHR2 gene, the absence of the toxic substance that triggered its adaptation might leave it at a disadvantage.

“If they clean up the river,” Wirgin said, “these fish may need to adapt again to the cleaner environment.”

Mark Hahn works in lab with colleague Diana Franks. (Photo by Tom Kleindinst, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

The WHOI portion of the study was funded by an NIH Superfund Research Program Center grant through the Superfund Research Center at Boston University.

The NYU work was funded by an NIH Superfund Research Program individual grant and an NIH Environmental Health Sciences Center grant.

“This research could not have been attempted without the unique multidisciplinary focus of our funding vehicle, Superfund Basic Research,” Wirgin said.

*Source: Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution