*The genomes of 17 common strains of lab mice were sequenced to advance genetic studies of human diseases*

Scientists have sequenced the genomes (genetic codes) of 17 strains of common lab mice–an achievement that lays the groundwork for the identification of genes responsible for important traits, including diseases that afflict both mice and humans.

Mice represent the premier genetic model system for studying human diseases. What’s more, the 17 strains of mice included in this study are the most common strains used in lab studies of human diseases. By enabling scientists to list all DNA differences between the 17 strains, the new genome sequences will speed the identification of subsets of mutations and genes that contribute to disease.

The study was conducted by an international team of researchers and was partially funded by the National Science Foundation. It is covered in this week’s issue of Nature.

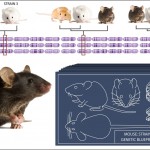

Seventeen mouse strains were sequenced. The genomes of a sample of these strains were compared to identify probable evolutionary relationships across the strains for various traits. Evolutionary relationships differ for each compared trait. Image credit: Zina Deretsky, National Science Foundation

This study also involved comparing the DNA sequences of four wild-derived mouse strains (three sub-species of mice and one separate mouse species) in order to reconstruct their evolutionary histories.

Comparisons of three strains of mice are shown in the illustration. The chromosomes of each mouse strain is represented by the row of purple chromosomes that bears its strain number. Each red slice through the chromosome rows identifies the genetic code for a particular trait–such as fur color, tail length and diabetes–in the three strains. By comparing the genetic codes for these and other traits across the strains, the researchers were able to identify probable evolutionary relationships across the strains for each trait. These evolutionary relationships are represented by the positions of the mice pictured in each mouse cluster appearing on the top of the illustration.

Results reveal striking variations in strain relationships across the genome. In other words, the evolutionary connection between mouse strains depends on which stretch of DNA is considered. For example, the mouse cluster on the top left corner of the illustration shows that the strain #1 and strain #2 mice are most closely related to each other for the associated trait and strain #3 is an outlier. The trait comparisons shown in the other two mouse clusters suggested different evolutionary relationships between the three strains.

“Mouse genomes are complex patchworks of different histories,” concluded Bret Payseur who worked with Michael White on this part of the study. (Both researchers are from the University of Wisconsin, Madison.)

These results underscore: 1) the importance of basing genetic comparisons between species on as much genomic information as possible; and 2) the potential complexities of studying the evolution of disease-causing mutations in order to help explain their mechanisms.

For more information, see press releases on this study issued by the University of Wisconsin and the Welcome Trust Sanger Institute.

*Source: National Science Foundation (NSF)