When Dr. Dieter Lindskog first began walking the halls of Yale School of Medicine a decade ago, people would stop him often to ask, “Are you by any chance related to …?” Now they stop him rarely, either because they know the answer or are too young to recognize the famous name — that of the grandfather who upended accepted tenets of medical practice and, in doing so, gave birth to the science and art of modern oncology.

“His shadow and legacy were long and broad,” Lindskog says. “As I was starting out here, there was certainly no one who didn’t know him.”

Dr. Gustaf Lindskog was a leading thoracic surgeon and chair of the Yale Department of Surgery in 1942. It was a perilous time: The United States feared that Germany was about to unleash chemical weapons against Allied soldiers.

Yale School of Medicine researchers had been participating in a top-secret government program to develop antidotes to these agents. While focused on the lethal effects of nitrogen mustard, one of the most deadly chemical weapons of the time, they noticed that it appeared to also kill cancer cells in mice.

Drs. Louis Goodman and Alfred Gilman of pharmacology had treated a mouse with an advanced lymphosarcoma. After just two injections of nitrogen mustard, the tumor began to soften and shrink. It was an exciting discovery, but after another round of treatment, the tumor grew resistant, and after 84 days the mouse died.

Still, the physicians considered the extended lifespan remarkable, and they started wondering whether nitrogen mustard could be used to help humans with cancer. They turned to their colleague at Yale, Dr. Gustaf Lindskog.

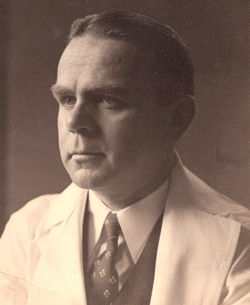

Dr. Dieter Lindskog stands next to his grandfather’s photo, which is part of a new exhibit at Smilow Cancer Hospital on the birth of chemotherapy. Image credit: Yale University

Lindskog had a patient, known only as J.D., who was 47 years old and dying. By the time he was admitted to New Haven Hospital (later to become Yale-New Haven Hospital) on Aug. 25, 1942, J.D. had massive head and neck tumors that had cut off his ability to speak, eat, or move his head. Months of radiation had done little to no good.

Lindskog approached his patient about receiving this experimental treatment with nitrogen mustard. Knowing he had run out of other options, J.D. willingly agreed and two days later became the first human patient to receive intravenous chemotherapy for cancer. In administering the treatment, Gustaf Lindskog launched a protocol for cancer care that would save millions of lives over the next 70 years.

But Dieter Lindskog knew nothing about all that, growing up in nearby Woodbridge. His grandfather had already retired by the time Lindskog was old enough to comprehend the implications. “He was very reserved and modest,” Lindskog recalls. “He never told me the story till I asked him about it.”

That story, which was uncovered thanks to dogged detective work by Yale physicians Dr. John E. Fenn and Dr. Robert Udelsman, must be understood within the context of a global war that demanded secrecy on every front, including in the lab. After his first chemotherapy treatment, J.D. received injections for several days, but because of the secrecy and censorship required, doctors couldn’t even note on his record that he was receiving nitrogen mustard — they referred to the injected material as “a lymphocidal chemical,” or “substance X.”

By Aug. 31, six days after his first injection, J.D. was improving. He was able to sleep comfortably in bed. Eating was easier, and he could move his head in a wider arc and cross his arms on his chest for the first time in weeks. By Sept. 6 his condition had improved markedly, and a month into his treatment, his cancer was undetectable.

Unfortunately, the cancer cells that lingered had become resistant to the nitrogen mustard. J.D.’s lymphosarcoma returned, and this time there was no treatment. He went downhill quickly, and on Dec. 1, 1942, the 96th day of his hospital stay, J.D. died.

Today, of course, students of oncology know about the seminal events of late 1942 in New Haven because of the long-lost records that were found and pieced together by doctors Fenn and Udelsman. But Gustaf Lindskog’s role was never fodder for conversation in the family home. Dieter Lindskog learned about his grandfather’s accomplishment by accident, while studying a ninth-grade textbook. “I recognized the names Goodman and Gillman, and then saw Lindskog. I went home and asked my parents, ‘What’s this about?’ They told me, ‘Oh yeah, that’s grandpa!’”

The youngster instantly had questions, and there was only one person who could answer them. “It was interesting to hear his recollection,” he recalls. “They had this mustard gas product they thought might be applicable to people. My grandfather had a patient who had exhausted all treatments and was about to die, and because he was willing to try anything, they gave it to him.”

Times were different then. Research could be conducted fairly easily. “It’s unimaginable, compared to today’s world,” Dieter Lindskog says. “He had a drug and a patient. He talked to him, told him it was experimental, and gave it to him. Today, that would be a nine-month process.” He gives the team credit, however, for quickly applying rigorous study techniques and approval processes to their experiments. “The first published clinical trial was not very long after.”

Gustaf Lindskog was not just a physician. He was also an administrator, chief of surgery at Yale for 26 years. And, his grandson says, he could be tough on those under him. When Dieter Lindskog was a child, his pediatrician told him how his grandfather chewed him out one day over how he had transfused a patient. The pediatrician was so flustered that he turned and walked straight into a plate glass wall. “Every year when I’d go for my exam I’d get to see his scar and hear the story.”

The medicine gene appears to have skipped a generation in the Lindskog family. Dieter’s father, Carl Lindskog, was a bank trust officer in New Haven and had a phobia about hospitals. “My father used to have a nightmare about being a doctor whose patient dies. He hears somebody behind him lean over and say, ‘His old man never would have lost him.’” Fortunately, Dieter Lindskog says he’s far enough away from the legacy that he doesn’t feel that particular kind of pressure.

Today, Dieter Lindskog is an orthopedic oncologist at Yale School of Medicine, specializing in bone and soft tissue sarcomas. And he has a lot of his grandfather in him. “Something drew me to the idea of saving someone’s life in addition to improving their function and well-being. It’s different from the rest of orthopaedics. Not much else deals with life and death issues.”

It’s been a long time since Gustaf Lindskog retired, but there are still reminders of his presence at Yale. The mother of one of Dieter Lindskog’s patients told him how his grandfather had saved her mother’s life. “Things came full circle there.”

Gustaf Lindskog never talked to his grandson about J.D.’s life, which began in Poland and ended, alone, in New Haven. “That’s not his style. He would never reveal personal information.” But Dieter Lindskog was still impressed by the relationship between the doctor and the patient who had nothing to lose. “It was scary and courageous. This was an opportunity to at least gain some knowledge for the ages.”

Gustaf Lindskog died in 2002, just short of his 100th birthday. He lived long enough to see his grandson go to medical school and return to Yale as a resident, but died before he joined the Yale faculty in 2004. Dieter Lindskog suspects it’s not entirely a coincidence that he wound up practicing in the same halls as his grandfather. “This is home. This was a wonderful opportunity. On some level, there’s probably that connection with him having been here.”

He takes the long view in talking about where cancer treatment is after 70 years, and where it still needs to go. “We’ve gotten to the point where for many cancers, chemotherapy is effective and curative. But for others, such as sarcomas, we’re not very far from where we were in 1942. For many tumors, we don’t have any effective treatments other than surgery.”

“For 70 years, it’s really been this shotgun treatment where you essentially preferentially poison tumor cells while trying to keep the rest of the patient alive,” he says. “Now we’re at the cusp of biologically identifying what’s causing these tumors in order to apply much more specific, guided treatments.”

Does he think his grandfather would be shocked at the world of oncology today? “No,” he says, adding, “He might be shocked that it took this long.”

– By Helen Dodson

*Source: Yale University