ANN ARBOR, Mich.— A non-invasive brain imaging technique gives new hope to patients with Parkinson’s disease in finding new and better treatment plans and tracking the disease progression, a new University of Michigan study shows.

The technique uses an MRI to measure resting state brain activity oscillations, said Rachael Seidler, associate professor in the School of Kinesiology and the Department of Psychology, and study author.

Neural oscillations in a resting state are normal, Seidler said. However, in the part of the brain affected by Parkinson’s, called the basal ganglia, those neural oscillations go haywire and spill into other parts of the brain, causing cognition, movement, memory and other problems. Think of a ripple in a pond spreading and disturbing the entire surface of the pond. Previously these neural oscillations were only available for study during brain surgery or in animal models.

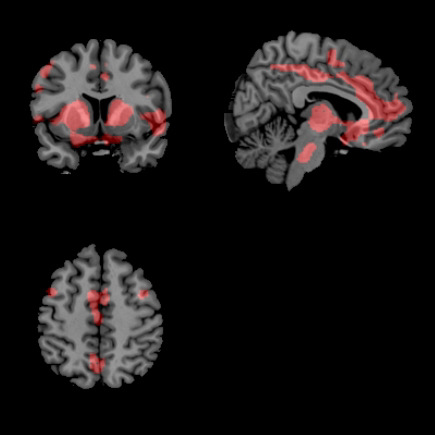

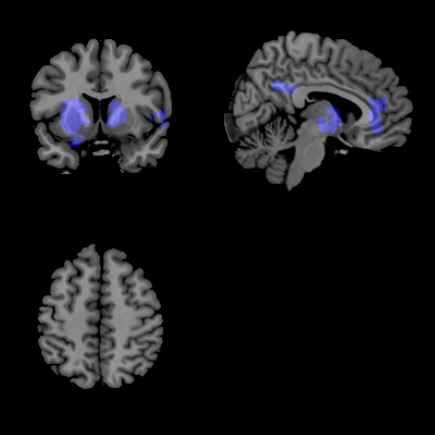

One drug that reduces these oscillations and subsequent disturbances in Parkinson’s is L-DOPA, Seidler said. Research subjects who hadn’t taken their morning L-DOPA came in twice for testing and either received a placebo pill or L-DOPA. When scanned in the MRI, the images showed that the increased oscillations were reduced by the L-DOPA.

About the images: Comparing the brains of two Parkinson’s patients. The unmedicated patient (top photo) shows more colored areas, which indicates spillover of the disruptive brain oscillations that happen from the basal ganglia to the cortex when patients didn’t take their medication. The patients (bottom photo) who took their L-DOPA show fewer areas of spillover. Image credit: University of Michigan

“The change in brain activity correlated with improvements in symptoms when patients were on versus off the medication,” Seidler said. “Thus we propose that the brain imaging technique we used should be a good, noninvasive approach for monitoring disease progression and evaluating new treatments.”

Surprisingly, the MRI imaging found that in some cases the L-DOPA even slowed the oscillations too much—think of this as the pond freezing. “In this instance you could use it (the imaging) to titrate the dose,” Seidler said.

The project involved four different departments. “This is one of the best collaborations,” Seidler said. “Biomedical engineering helped with the technical aspects of the analysis, and neurology and radiology helped to recruit the patients and prescreened them to see whether they could tolerate the drug protocol. I couldn’t have done it without them, so to me that was just super exciting.”

Study collaborators are Scott Peltier of the U-M College of Engineering, Youngbin Kwak, U-M Neuroscience Program, and Nicholaas Bohnen, Martin Muller, and Praveen Dayalu, all of U-M Medical School.

Next steps may include analyzing the same data for the size of the oscillations—the ripple in the pond—and how the size relates to cognitive and motor performance in newly diagnosed Parkinson’s patients.

*Source: University of Michigan