ANN ARBOR — When we’re strolling down memory lane, our brains recall just as much information while walking as while standing still—findings that contradict the popular science notion that walking hinders one’s ability to think.

University of Michigan researchers at the School of Kinesiology and the College of Engineering examined how well study participants performed a very complex spatial cognitive task while walking versus standing still.

“We’re saying that at least for this task, which is fairly complicated, walking and thinking does not compromise your thinking ability at all,” said Julia Kline, a U-M doctoral candidate in biomedical engineering and first author on the study, which appears online in Frontiers in Human Neuroscience.

The finding surprised researchers, who expected to see decreased thinking performance with increased walking speed, Kline said. The 2011 best-selling book “Thinking Fast and Slow” suggests that because walking requires mental effort, walking may hinder our ability to think when compared to standing still.

“Past studies that have compared mental performance at a slow walking speed and standing have not found any differences, but our study is the first to show that the walking speed doesn’t matter,” said Daniel Ferris, professor of kinesiology and biomedical engineering and senior author of the paper.

“Given the health benefits of walking, we should not discourage people from walking and thinking when they want.”

Ferris offered one caveat: previous research has shown that walking performance can be impaired in the elderly when they dual-task during gait.

Ferris, Kline and Katherine Poggensee of U-M’s Human Neuromechanics Laboratory measured the ability of young, healthy participants to memorize numbers and their placement on a grid, and then enter those numbers correctly with a keypad while walking different speeds and standing still.

“Think of filling numbers one through nine on a tic-tac-toe grid and then remembering where they all are,” Ferris said. “At every walking speed and standing still, participants entered about half the numbers correctly.”

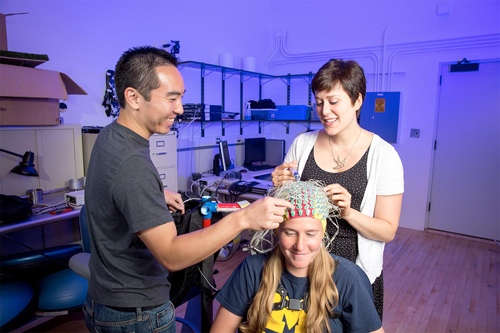

From left, biomedical engineering PhD student, Grant Hanada, Kinesiology undergraduate student, Maggie Smith, and Julia Kline, biomedical engineering PhD student. Image credit: Ferris Lab

While speed didn’t change task performance, people took wider steps when performing the task than when they were only walking, which may be to compensate and stay balanced while concentrating, Kline said.

All participants showed increased activity in areas of the brain associated with spatial relationships and short-term memory during the cognitive task. In keeping with the U-M findings, a recent Stanford study suggested that walking fueled creativity.

In addition to good news for treadmill-desk users or people who like to think on the move, the study provides a useful scientific tool by demonstrating that it’s possible to collect accurate EEG data on moving subjects, Kline said.

This is important to researchers who study the brain and are concerned about getting accurate results when the subjects aren’t perfectly still. U-M researchers achieved their EEG results by applying different signal-processing techniques to eliminate the movement “noise” from the EEG signal.

– By Laura Bailey

*Source: University of Michigan