UA researcher Don Fallis has spent years studying the existence of lies and deception in social interactions and popular culture, developing a framework to better explain the difference between an honest mistake and an intentional lie.

Don Fallis searches for disinformation, the process of intentionally disseminating misleading information, in political dialogue, books, television and film – and he finds examples most everywhere.

That may come of little surprise, given the fictional nature of many entertainment-based cultural exchanges.

But for Fallis, a philosopher who studies social processes and information exchanges, the presence of disinformation – intentional lying, not honest mistakes or misinformation – allows for an important analysis of human tendencies, in fictional form or not.

“Lying and deception are ubiquitous parts of human life,” said Fallis, a professor in the University of Arizona School of Information Resources and Library Science, or SIRLS.

“In fact, some people have argued that the reason humans have developed such great cognitive capacity beyond the rest of the animal kingdom is that we’ve developed the capacity and need to deceive,” said Fallis, who also has a faculty position in the UA’s philosophy department. “Lying and deception are important to the human condition.”

For example, lying can serve as an important emotional buffer for some.

But what is concerning to Fallis, and what he persistently argues, is that disinformation robs us of certain other important capacities.

“There are structural phenomena that exist that make it difficult to be critical thinkers and to identify inaccurate information,” Fallis said. “And there is something particularly dangerous about disinformation – when someone is actively trying to mislead us.”

Fallis points to the obvious example of false information in advertising and in the political sphere, but there is a less obvious and less studied domain that chiefly concerns him: popular culture. And this is an area that UA philosophy professor Terry Horgan said is deserving of much more attention.

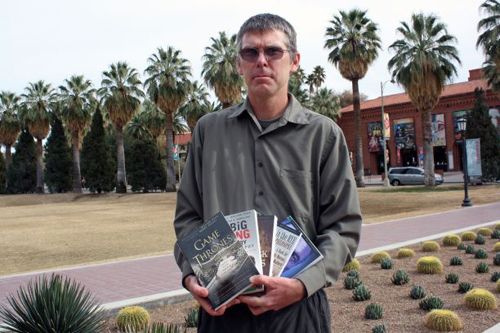

About UA researcher Don Fallis, UA philosophy professor Terry Horgan said: “Don’s work is of cutting-edge importance as society seeks to adapt to new information-technologies while also avoiding the problems and perils that arise from misinformation.” (Photo credit: Beatriz Verdugo/UANews)

Horgan noted that Fallis’ work falls under an emerging interdisciplinary field of social epistemology, which investigates how social beliefs are formed and, then, justified.

“A specific, important, issue within this field concerns the nature of lying and deception; we need to understand what constitutes lying and deception in order to be positioned to form informed critiques of certain social sources of so-called information as really being sources of disinformation,” Horgan said.

What Fallis contributes, both to his field of study and to members of the general public interested in exploring comparable topics, is a framework or way of thinking about disinformation.

“On a social-pragmatic level, these issues are vital in the current social milieu, especially in light of the recent explosion of phenomena like online blog sites, television news shows that have a strong political bias, talk show radio programs and online sources like Google and Wikipedia,” Horgan said.

“On the theoretical level, social epistemology is an increasingly important branch of the theory of knowledge, and the nature of lying and deception is a central issue within social epistemology itself,” he also said.

To that point, Fallis has published scholarly articles, essays and book chapters, including those in the Philosophy and Popular Culture book series on “Game of Thrones,” “The Big Bang Theory,” “The Catcher in the Rye” and others. Fallis also has articles forthcoming on the HBO television shows “Boardwalk Empire” and “The Wire.”

“Don is unusually good at unearthing, within such popular-culture sources, richly nuanced fictional examples of important philosophical problems, problems that have a significant impact on real-life questions we all face about how to live our lives, what to believe, what to value, how to raise our children, and what kind of society we wish to live in,” Horgan said.

“His work on lying and deception is very well respected in scholarly circles and has been much discussed among scholars working on this topic, as it deserves to be,” Horgan also said.

So, how do we reduce the instance of intentional or unintentional misinformation?

Fallis teaches a course on information quality and noted two prevailing ways to address disinformation and misinformation: build better detectors, like lie detectors and surveillance systems, to identify bad information, and better train individuals to detect lies.

Neither is proficient enough to address the problem with disinformation, though some existing and emerging techniques, like certification stamps on medical information websites and improved models for predicting deceptive behaviors, for example, are hopeful, Fallis said.

Much more is needed by way of research and in training the next population of information specialists and consumers of knowledge and information.

“We will be able to do that when we have a greater understanding about what disinformation is,” Fallis said. “That is why I am looking carefully at this conceptual question. In order to take effective steps to deal with the threat of disinformation, we first need to know exactly what disinformation is. “

– By La Monica Everett-Haynes

*Source: The University of Arizona