Carvacrol, the primary active component in oregano oil, effectively kills norovirus, a common cause of foodborne illness outbreaks in hospitals, schools and cruise ships.

A study led by University of Arizona researcher Kelly Bright has found that carvacrol – the substance in oregano oil that gives the pizza herb its distinctive warm and aromatic smell and flavor – is effective against norovirus, causing the breakdown of the virus’ tough outer coat. The research is published in the Society for Applied Microbiology’s Journal of Applied Microbiology.

Norovirus, also known as the winter vomiting disease, is the leading cause of vomiting and diarrhea around the world. It is particularly problematic in nursing homes, hospitals, cruise ships and schools, and is the most common cause of foodborne-disease outbreaks. Although the disease is unpleasant, most people recover fully within a few days. But for people with an existing serious medical problem, this highly infectious virus can be dangerous.

“Carvacrol could potentially be used as a food sanitizer and possibly as a surface sanitizer, particularly in conjunction with other antimicrobials,” said Kelly Bright, an associate research scientist in the Department of Soil, Water and Environmental Science, part of the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences. “We have some work to do to assess its potential but carvacrol is an interesting prospect.”

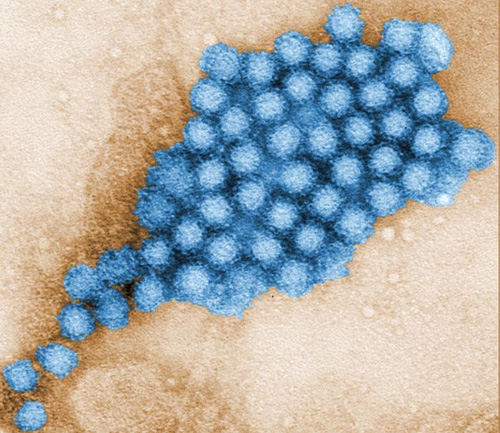

Norovirus particles have a tough outer shell that makes them persistent in the environment and difficult to eliminate. (Photo credit: U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention)

The human form of norovirus is challenging to work with and is resistant to most antimicrobials, like hydrogen peroxide, bleach, ammonia and alcohol.

“It’s is a very tough virus,” Bright said. “Norovirus can survive for weeks and even months in the environment, which makes it so prevalent on cruise ships and sometimes causes repeat outbreaks. When a ship returns to port after an outbreak, they clean it from top to bottom to remove the contamination, but it is sometimes impossible to get it all, especially on carpeted and upholstered surfaces.”

Bright and her team – former graduate student Damian Gilling, former visiting scholar Masaaki Kitajima and current doctoral student Jason Torrey – determined whether oregano oil and carvacrol, the primary active component in oregano oil, were effective against mouse norovirus. In the experiments, oregano oil had limited efficacy, but carvacrol resulted in a nearly 10,000-fold reduction in viral infectivity within an hour. In other words, it is 99.99 percent effective against the virus.

“Carvacrol does not act as quickly as bleach, which will act in minutes or even seconds, but it is still effective,” Bright said. “If you put bleach on a surface, organic matter like vomit will use up the bleach, leaving little behind to kill the virus. Carvacrol, on the other hand, is not as sensitive to organic matter because it comes from plants. It takes a little bit longer but it has a longer-lasting antimicrobial residue on surfaces.”

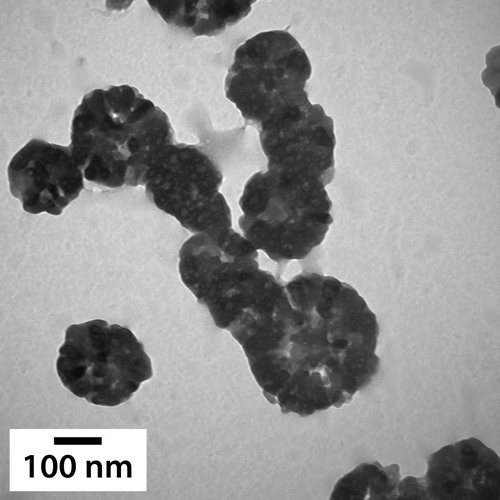

Mouse norovirus treated with carvacrol viewed under a microscope. The virus particles have expanded to about six times their normal size. (The scale in the image of 100 nanometers equates to about six-hundredths of the diameter of a human hair.) The experiments showed that the shells of these viruses are no longer intact and will continue to expand in size until they disintegrate into pieces. (Photo credit: Kelly Bright)

In addition, since carvacrol is a plant compound, it is generally regarded as safe for human consumption, Bright added. “You could use it on foods such as fresh produce or meats and on food contact surfaces in the kitchen where you would not want to use some other types of antimicrobial agents.”

This is also the first study that looks at the mechanism of breakdown in detail of a plant antimicrobial on a nonenveloped virus, Bright explained. Those viruses lack the thin biological “wrapper” that surround enveloped viruses such as the flu virus and others that are often at home in the respiratory tract. Because of the fragile nature of this wrapping surface, those viruses break down more easily in the environment. Nonenveloped viruses like noroviruses tend to be the ones that target the gastrointestinal tract. Their tough outer protein shell – called the capsid – makes them resistant against stomach acid and allows them to travel through the gastrointestinal tract unharmed. Bright’s research revealed the exact mechanism of how this plant compound kills a nonenveloped virus.

“Carvacrol acts directly on the virus’ outer shell and breaks it down,” she said. “The virus needs that capsid to attach to the human cell, so if you break down that shell, it won’t be able to cause an infection. In addition, it breaks down the virus’ RNA genome. These effects are therefore likely irreversible, so the mechanism of action is an example of true virus inactivation.”

The good news is that because carvacrol acts on the external proteins of the virus, it is unlikely that norovirus would ever develop resistance. It is also safe, noncorrosive and it won’t produce any noxious fumes or harmful byproducts. This makes it particularly attractive for use in settings where people are likely to be sensitive to traditional bleach or alcohol-based cleaners, such as schools, hospitals, long-term care facilities, child day care centers, and drug and alcohol rehabilitation facilities.

This research was funded by the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Organic Research and Extension Initiative.

– By Society for Applied Microbiology and Daniel Stolte

*Source: The University of Arizona