ANN ARBOR, Mich.—Within 24 hours of culturing adult human stem cells on a new type of matrix, University of Michigan researchers were able to make predictions about how the cells would differentiate, or what type of tissue they would become. Their results are published in the Aug. 1 edition of Nature Methods.

Differentiation is the process of stem cells morphing into other types of cells. Understanding it is key to developing future stem cell-based regenerative therapies.

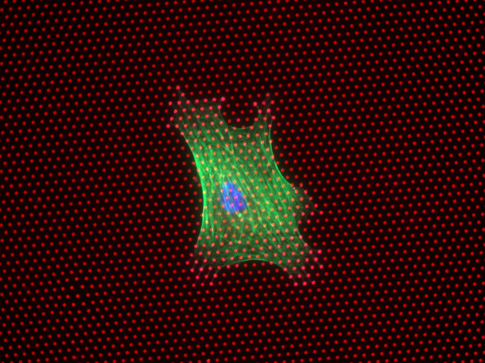

About the image: An immunofluorescence image of a human mesenchymal stem cell growing on a plate of microposts, which have the approximate consistency of Silly Putty. This image was taken after one day of culturing. The red dots are the microposts, which are relatively short in this sample. The green is the cell and the blue is its nucleus. This cell will differentiate into a bone cell. Image credit: University of Michigan

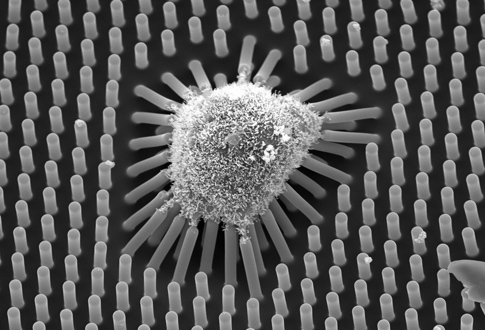

About the image: An image taken with a scanning electron microscope of a human mesenchymal stem cell growing on a plate of long microposts approximately 13 microns in length. After one day of culturing, this cell exerts centripetal force, which can be seen in the bending of the microposts. This cell will differentiate into a fat cell. Image credit: University of Michigan

In this study, Fu and his colleagues examined stem cell mechanics, the slight forces the cells exert on the materials they are attached to. These traction forces were suspected to be involved in differentiation, but they have not been as widely studied as the chemical triggers. In this paper, the researchers show that the stiffness of the material on which stem cells are cultivated in a lab does, in fact, help to determine what type of cells they turn into.

The researchers built a novel type of stem cell matrix, or scaffold, whose stiffness can be adjusted without altering its chemical composition, which cannot be done with conventional stem cell growth matrices, Fu said.

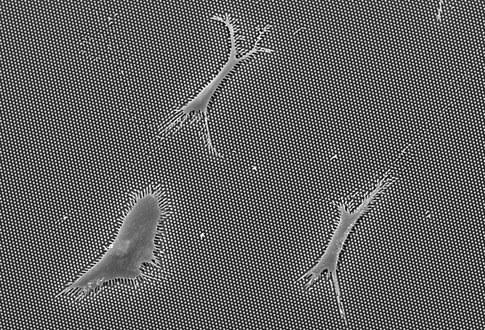

About the image: An image taken with a scanning electron microscope of human mesenchymal stem cells growing on a plate of short microposts. After one day of culturing, these cells spread more than cells cultured on long microposts. These will differentiate into bone cells. Even though these cells bend their shorter microposts less than their counterparts growing on longer microposts, they exert greater force to do so. Image credit: University of Michigan

The new scaffold resembles an ultrafine carpet of “microposts,” hair-like projections made of the elastic polymer polydimethylsiloxane—a key component in Silly Putty, Fu said. By adjusting the height of the microposts, the researchers were able to adjust the rigidity of the matrix.

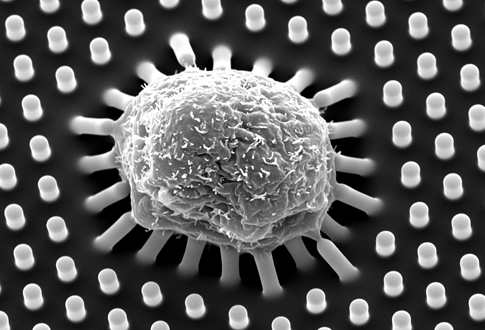

About the image: An image taken with a scanning electron microscope of a human mesenchymal stem cell growing on a plate of long microposts, which can be seen bending in response to the cell’s forces. This will become a fat cell. The stem cells round up on taller and softer microposts and differentiate into fat cells. They spread out on the shorter and stiffer substrates and become bone cells. Image credit: University of Michigan

Once the researchers observed the cells differentiating according to the mechanical stiffness of the substrate, they decided to measure the cellular traction forces throughout the culturing process to see if they could predict how the cells would differentiate.

Using a technique called fluorescent microscopy, the researchers measured the bending of the microposts in order to quantify the traction forces.

The paper is called “Mechanical regulation of cell function using geometrically modulated elastomeric substrates.” This work was conducted in Dr. Christopher Chen’s group in the Department of Bioengineering at the University of Pennsylvania. The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health and the American Heart Association.