EAST LANSING, Mich. — Research by Michigan State University astronomers has scientists re-thinking the fates of black holes, particularly in groups of stars known as globular clusters.

The research of Jay Strader, MSU assistant professor of physics and astronomy, and colleagues focused on a cluster called Messier 22, or M22, a collection of hundreds of thousands of stars located about 10,000 light years from Earth. Using images of unprecedented depth observed at radio wavelengths, Strader and his team were surprised to find not one but two black holes in the cluster.

It was surprising, Strader said, because normally when black holes live in such an environment, it is assumed that only one will survive. The theory is that when black holes form in a star cluster, they tend to fall toward the center of the cluster. It’s then that they start a violent gravitational dance in which all of them, except one, are unceremoniously tossed from the cluster.

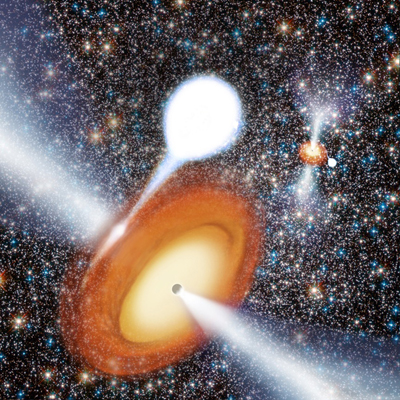

An artist’s rendering of two black holes in a globular star cluster. The matter first falls into extended accretion discs (rendered here in yellow-orange) around the black holes, and much of it is ejected through conical jets rather than being ingested by the black holes. The background is a Hubble Space Telescope image. Image by Benjamin de Bivort (Harvard University).

“There is supposed to be only one survivor possible,” Strader said. “Finding two black holes, instead of one, in this globular cluster definitely changes the picture.

“The fact that we discovered two in this cluster suggests that theory isn’t right. These clusters are hanging onto more black holes, but the reason is not clear.”

One theory is that the black holes themselves gradually expand the central parts of the cluster, reducing the density and thus the rate at which black holes eject each other through their gravitational dance. Alternatively, the cluster may not be as far along in the process of contracting as previously thought, again reducing the density of the core.

“Future radio observations with the Very Large Array telescope will help us learn about the ultimate fate of black holes in globular clusters,” said Laura Chomiuk, an MSU post-doctoral fellow and member of the research team.

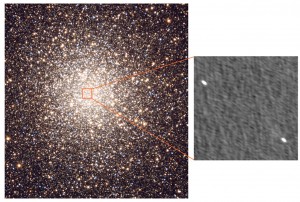

Images of the globular star cluster M22. On the left is an optical image, showing the dense stellar environment where the two newly discovered black holes dwell (orange square). The right panel is a detail of the VLA radio image. The white point sources are the radio detections of the black holes. Photo courtesy of D. Matthews/A. Block/NOAO/AURA/NSF.

The two black holes were discovered using the National Science Foundation’s Karl G. Jansky Very Large Array telescope in New Mexico. They were the first black holes to be found in any globular cluster in our own Milky Way Galaxy, and also are the first found by radio, instead of X-ray, observations.

Strader and Chomiuk worked with Thomas Maccarone of the University of Southampton in the U.K.; James Miller-Jones, of the International Centre for Radio Astronomy Research at Curtin University; and Anil Seth of the University of Utah.

MSU physics and astronomy assistant professor Jay Strader stands before the Very Large Array telescope in New Mexico. Strader and colleagues used the VLA to discover two black holes in a cluster of stars known as M22. Photo by Laura Chomiuk.

The scientists published their findings in the Oct. 3 issue of the journal Nature.

Laura Chomiuk is an MSU post-doctoral fellow who was part of a team that used the Very Large Array telescope in New Mexico to discover two black holes in the M22 star cluster. Photo by Jay Strader.

*Source: Michigan State University