History tells us that Paul Chomedey de Maisonneuve erected a cross atop Mount Royal in 1643 to thank God for sparing the city from flooding. However, according to 18th century archival documents, the cross was planted two kilometers away from where it is today.

“I discovered a document reporting the trial of a man accused of murder and living near the cross in 1750,” says Theresa Gabos. “When going through the aveux et dénombrements (the land and assets belonging to an individual) of the time, we learn that this man lived near the current intersection of Sherbrooke Street and chemin de la Côte-des-Neiges. This wasn’t the De Maisonneuve cross, but rather a replica of the original that had rotted. Nonetheless, this probably reveals the original location of the cross and highlights the fact that perception of the mountain and its summit has evolved with time.”

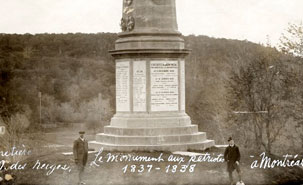

A farm was situated where Notre-Dame-des-Neiges Cemetery is located today. Image credit: University of Montreal

For the past two years, Theresa Gabos and Valerie Janssen, master’s students at the Université de Montréal Department of Archeology, have explored the archeological potential of Mount Royal. “In a way, we are conducting an inventory of the archeological resources of the mountain by documenting its extensive human occupation,” says Janssen. “For instance, the remains of homes, such as foundations, or objects abandoned by occupants and even pollen that indicates the agricultural development of certain areas at the time.”

This research project will serve both their theses, directed by professors Brad Loewen and Adrian Burke, as well as a database of historical mapping that will be developed by the city of Montreal and by the Ministry of Culture, Communications and the Status of Women.

“The archeological heritage of Mount Royal remains unknown,” says Gabos. “Authorities want to protect it, but to do so they must first know what is buried there.”

That is what is keeping Gabos and Janssen busy as they examine ancient maps, photos, notarized documents and the aveux et dénombrements. They also canvassed various parts of the mountain searching for visible relics. All their data is then entered into a geographic information system.

“We then produce several superimposable maps that illustrate the evolution of the mountain,” says Janssen. “The software can position the buildings as they were in 1871, provide the 1731 cadastre and cover the image with 2011 vegetation.”

A forest with a story

The students went back to the foundations of the city and made stunning discoveries along the way. “People see Mount Royal as a natural forest,” says Janssen. “However, we once practiced agriculture on the mountain, cut down and replanted the forest…Today’s vegetation is the product of yesterday’s human activity.”

The landscape has a memory. Behind the Sir George-Étienne Cartier monument, the trees are almost perfectly aligned as a result of the landscaping of Benjamin Hall Esquire’s orchard who had a villa nearby in the 19th century. “These trees were probably planted after the creation of Mount Royal Park, but maintain the positioning of the earlier fruit trees,” says Gabos.

In front of the Montreal General Hospital on Cedar Avenue is an area of tall grass with scattered clusters of trees that could be relics of the Children’s Memorial Hospital, one of the first pediatric hospitals built between 1907 and 1909.

Gabos and Janssen took a close look at the Université de Montréal land as well. In the 19th century, the site belonged to a farmer named John Swail. The foundations of his house are below the Maximilien-Caron pavilion.

A farm and fences were on the current site of the Notre-Dame-des-Neiges cemetery. A 1923 picture of Alfred Laliberté testifies to the fact.

The students were able to piece together various phases of deforestation thanks to several notarized documents. “We located the parcels of land in question, the variety of wood that was cut, who it was sold to and why it was bought,” says Janssen. “We dug up documents highlighting that upon running out of white oak, red oak was used instead to build ships…and it was a disaster because it rots much too quickly!”

Gabos and Janssen hope their efforts will raise public awareness about the conservation of archeological resources on Mount Royal. “Some people destroy potential archeological sites by using metal detectors and pillaging the area. Conserving this area allows us to deepen our understanding of the mountain and sharing that knowledge with the public. After all, it’s the heritage of all Montrealers.”

– This article was translated to English from a work originally published in French by Marie Lambert-Chan

*Source: University of Montreal