*NSF enabled the assembly of an international, interdisciplinary team that was the first to quantitatively document body size patterns over the past 100 million years*

Researchers have demonstrated that the extinction of dinosaurs some 65 million years ago paved the way for mammals to get bigger, about a thousand times larger than they had been when dinosaurs roamed the earth. The study, released in the journal Science, is the first to quantitatively document the patterns of body size of mammals after the existence of dinosaurs.

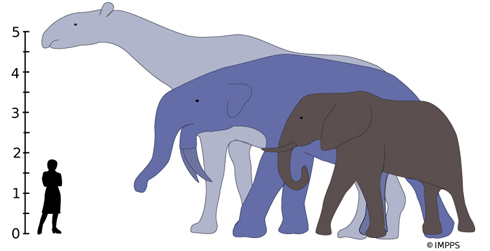

About the Image: The largest land mammals that ever lived, Indricotherium and Deinotherium, would have towered over the living African Elephant. Indricotherium lived during the Eocene to the Oligocene Epoch (37 to 23 million years ago) and reached a mass of 15,000 kg, while Deinotherium was around from the late-Miocene until the early Pleistocene (8.5 to 2.7 million years ago) and weighed as much as 17,000 kg. Image credit: NSF RCN IMPPS

The research, funded by a National Science Foundation (NSF) Research Coordination Network (RCN) grant, led by Principal Investigator Felisa Smith of the University of New Mexico, brought together an international team of paleontologists, evolutionary biologists and macroecologists from universities throughout the United States and around the world.

RCN grants began in NSF’s Directorate for Biological Sciences to encourage and foster communications and collaborations among scientists with common goals and interests. Groups of investigators are supported to communicate and coordinate their research efforts across disciplinary, organizational, institutional and geographical boundaries. The proposed networking activities each focus on a theme: a broad research question, a specific group of organisms, or particular technologies or approaches. Innovative ideas for implementing novel networking strategies to promote research coordination and collaboration that enable new research directions or advancement of a field are especially encouraged. What results are diverse, multi-disciplinary research teams that harness and synthesize different insights and data to achieve new, exciting discoveries.

“The findings on mammal size detailed in Science are evidence of the value of coordination networks, and of their success in bringing together scientists who have not worked together in the past,” said NSF Program Manager Saran Twombly. “Smith’s group had combined data in a new synthesis to advance our understanding of the evolution of body size.”

Based on the success of research funded by RCN grants in NSF’s Directorate for Biological Sciences, the program has been replicated in other directorates and offices throughout the foundation, including the directorates for Mathematical & Physical Sciences; Geosciences; Education & Human Resources and Social, Behavioral and Economic Sciences; as well as the offices of Polar Programs, International Science and Engineering, and Cyberinfrastructure.

About the video: Principal investigator Felisa Smith from the University of New Mexico describes the discovery. She discusses her research in its goals; she describes how the demise of dinosaurs paved the way for mammals to get bigger; and she outlines the results of the data. Video credit: Videotaped by Steve Carr, University of New Mexico Edited by Lisa-Joy Zgorski, Steve McNally, and John Wassel, NSF

About the video: Principal investigator Felisa Smith from the University of New Mexico describes the composition of her research team and the manner in which the team collected, organized and synthesized data to quantitatively explore the patterns of body size of mammals after the demise of the dinosaurs. Video credit: Videotaped by Steve Carr, University of New Mexico Edited by Lisa-Joy Zgorski, Steve McNally, and John Wassel, NSF

*Source: National Science Foundation (NSF)