A team of UA geoscientists figured out how China’s Loess Plateau, a dust deposit the size of the state of Arizona, came to be. Dust deposits known as loess often create good agricultural soil.

China’s Loess Plateau was formed by wind alternately depositing dust or removing dust over the last 2.6 million years, according to a new report from University of Arizona geoscientists.

The study is the first to explain how the steep-fronted plateau formed.

Geoscientist Fulong Cai stands on a linear ridge on top of China’s Loess Plateau and looks across a river valley at another of the plateau’s linear ridges. The high hills in the far background are on the edge of the plateau, which drops about 1,300 feet to the Mu Us Desert to the northwest. (Photo credit: Paul Kapp/ UA Department of Geosciences)

Wind blew dust from what is now the Mu Us Desert into the huge pile of consolidated dust known as the Loess Plateau, said lead author Paul Kapp, a UA professor of geosciences.

Just as a leaf blower clears an area by piling leaves up along the edge, the wind did the same thing with the dust that was once in the Mu Us Desert.

“If the blower keeps blowing the leaves, they move backward and the pile of leaves gets bigger,” Kapp said. “There’s a boundary between the area of leaves and no leaves.”

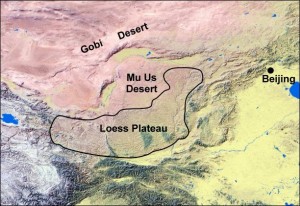

Map showing the location of China’s Loess Plateau. Image credit: Paul Kapp/ UA Department of Geosciences (Click image to enlarge)

About the size of the state of Arizona, the Loess Plateau is the largest accumulation of dust on Earth. Deposits of wind-blown dust known as “loess” generally create good agricultural soil and are found in many parts of the world, including the U.S. Midwest.

The UA team also found that, just as a leaf blower moves a pile of leaves away from itself, wind scours the face of the plateau so forcefully that the plateau is slowly moving downwind.

“You have a dust-fall event and then you have a wind event that blows some of the dust away,” Kapp said. “The plateau is not static. It’s moving in a windward direction.”

Linear ridges on the top of the Loess Plateau are also sculpted by the wind, the researchers found.

“The significance of wind erosion shaping the landscape is generally unappreciated,” Kapp said. “It’s more important than previously thought.”

The team’s paper, “From dust to dust: Quaternary wind erosion of the Mu Us Desert and the Loess Plateau, China,” is scheduled for publication in the September issue of the journal Geology and is currently online: https://geology.gsapubs.org/content/early/2015/07/28/G36724.1.abstract.

Kapp’s co-authors are UA geoscientists Alex Pullen, Jon Pelletier, Joellen Russell, Paul Goodman and former UA geosciences postdoctoral researcher Fulong Cai, now at the Institute of Tibetan Plateau Research in Beijing. The National Science Foundation funded the research.

To track down the source of the Loess Plateau’s dust, Kapp, Pullen and Cai went to China’s deserts in 2013 during March – prime season for dust storms. The researchers hoped to experience dust storms first-hand.

While standing atop one of the plateau’s linear ridges during a dust storm, the researchers noticed the wind was blowing parallel to the ridge’s long axis.

During a windstorm on China’s Loess Plateau, geoscientist Fulong Cai uses a plastic bag as a wind sock to show that the wind blows parallel to the linear ridge he and Wang Zhao are standing on. Roads in this area run along the ridges. (Photo Credit: Paul Kapp/ UA Department of Geosciences)

Kapp said they each had the same realization at the same time: The plateau itself was being sculpted by the wind. The plateau is not just a sink for dust, but is also a source of dust.

“You have to live it for it to really sink in,” he said. “You have to be out there in the field when the wind is blowing.”

Once back at the UA, Kapp fired up Google Earth to see satellite images of the plateau. He saw linear ridges just a few kilometers long – ridges like the ones he’d stood on.

To learn more, he started mapping the ridges in the satellite images.

“I mapped stuff like crazy, for weeks and weeks – I measured the orientation of about three thousand ridges from these images,” he said.

The ridges ran northwest-southeast in the northern part of the plateau and ran more north-south in the southern part.

To compare the orientation of the ridges to the orientation of the winds, he asked Russell to make a map of the modern-day wind patterns over the Mu Us desert and the Loess Plateau.

The wind pattern map, especially the winter and spring dust storm winds, matched the orientation of the ridges on top of the plateau.

“I’ve never seen anyone look at the wind-related geomorphology and actually relate it to climatology at the large scale of the entire Mu Us Desert and Loess Plateau,” Kapp said. “It’s a rare approach.”

The team’s ideas definitely are applicable to the formation of other areas of loess deposits on Earth, Kapp said, adding, “But nothing compares to the size of the Loess Plateau.”

He continues to be fascinated by how wind shapes planets. Kapp’s next step is looking at other wind-eroded landscapes on Earth and also on Mars.

– By Mari N. Jensen

*Source: The University of Arizona