In Africa 140 years ago, David Livingstone, the Victorian explorer, met Henry M. Stanley of the New York Herald and gave him a harrowing account of a massacre he witnessed, in which slave traders slaughtered 400 innocent people. Stanley’s press reports prompted the British government to close the East African slave trade, secured Livingstone’s place in history and launched Stanley’s own career as an imperialist in Africa.

Today, an international team of scholars and scientists led by Dr. Adrian Wisnicki of Indiana University of Pennsylvania, publishes the results of an 18-month project to recover Livingstone’s original account of the massacre. The story, found in a diary that was illegible until it was restored with advanced digital imaging, offers a unique insight into Livingstone’s mind during the greatest crisis of his last expedition, on which he would die in 1873.

Livingstone’s 1871 Field Diary is a free online public resource published by the UCLA Digital Library Program in Los Angeles (https://livingstone.library.ucla.edu/1871diary/). The project was made possible by the generous funding and support provided by the National Endowment for the Humanities (https://www.neh.gov/), an independent grant-making agency of the U.S. government dedicated to supporting research, education, preservation and public programs. The British Academy has also helped fund the endeavour. With these grants, the research and all the data is made available to advance humanities and technology studies across the United States and globally.

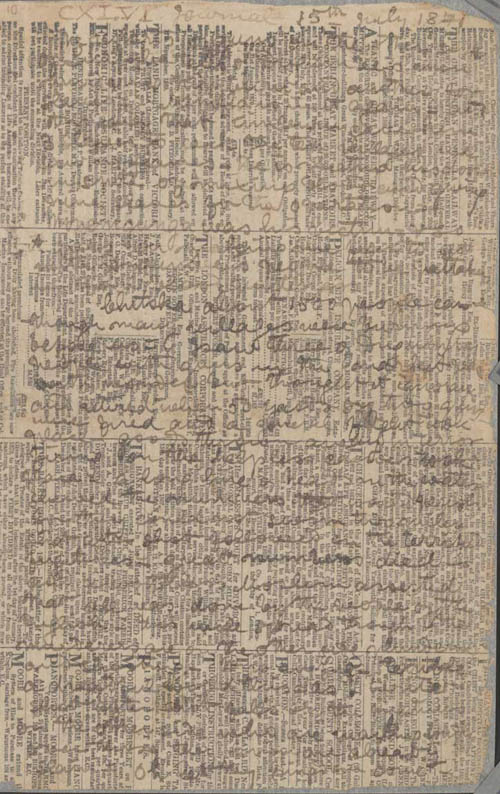

The story the diary tells is electrifying. Livingstone had once been a national hero, but when he wrote this diary, he had been forgotten by the public and was stranded without supplies in Central Africa. A dedicated writer, he made ink from berry seeds and wrote over the pages of a single copy of the London Standard — the precursor to today’s Evening Standard. Exposed to the African environment, the manuscript deteriorated rapidly and today is virtually invisible to the naked eye.

The diary depicts, in Livingstone’s words, “the unspeakable horror” of the slave trade in what is now the Eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. It provides an eye-witness account of the shocking massacre, perpetrated by armed slave traders in Nyangwe, a Congolese village. The event forced Livingstone to change his travel plans and led to his famous meeting with Stanley. Had Stanley not found Livingstone and greeted him with the words “Dr. Livingstone, I presume?”, the world might never have heard of Livingstone again.

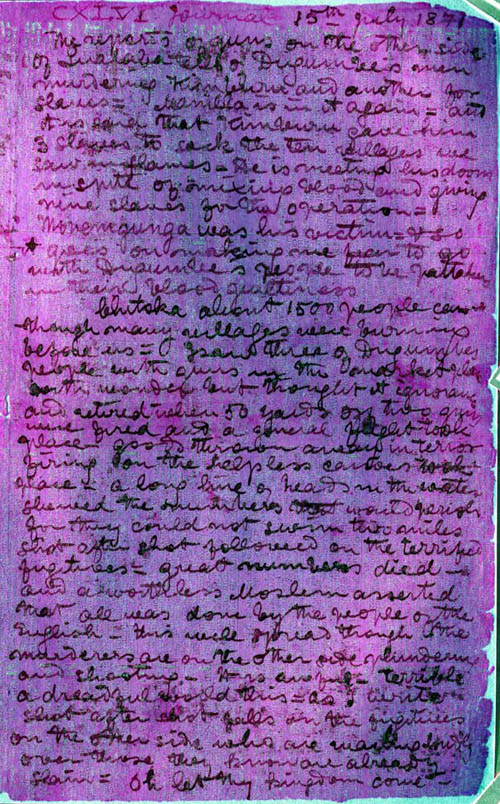

Livingstone diary under spectral light. Page from 1871 diary of Dr. Stanley Livingstone, viewed through spectral imaging. Image credit: University of California

The massacre is one of the most important events in “The Last Journals of David Livingstone” (1874), edited after Livingstone’s death in 1873 by his friend Horace Waller. Until now, this book was the main source for historians and biographers. However, critical and forensic analysis of the original 1871 text reveals a very different story from Waller’s heavily edited version. In particular, it sheds light on a heart-stopping moment when Livingstone gazes with “wonder” as three Arab slavers with guns enter the market in Nyangwe, where 1,500 people are gathered, most of them women:

“50 yards off two guns were fired and a general flight took place — shot after shot followed on the terrified fugitives — great numbers died — It is awful — terrible, a dreadful world this,” writes Livingstone in despair as he witnesses the massacre. “As I write, shot after shot falls on the fugitives on the other side [of the river] who are wailing loudly over those they know are already slain — Oh let thy kingdom come.”

Livingstone diary page. Page from 1871 diary of Dr. Stanley Livingstone, viewed under natural light. Image credit: University of California

Wisnicki, an assistant professor at Indiana University of Pennsylvania and an honorary research fellow at Birkbeck, University of London, says, “Evidence in the diary suggests that members of Livingstone’s party might have been involved in the massacre. Livingstone seems to have considered this possibility and this, together with his failure to intervene, appears to have left him with a profound sense of remorse. In copying over the 1871 diary into his journal, Livingstone decided to rewrite or remove a series of problematic passages. His revised journal account, on which the 1874 book is based, did not reflect his original record. It’s taken 140 years to discover Livingstone’s original words and reveal the many secrets of the original diary.”

The original account of the massacre is just one of many passages in the diary that are significantly different from the 1874 book.

“Livingstone would never have published this private diary in his own lifetime,” says Wisnicki. “In particular, his attitude to the liberated slaves in his entourage is one of disgust — an attitude greatly at odds with his public persona as a dedicated abolitionist.”

Wisnicki anticipates that the publication of the 1871 diary will change the way history interprets Livingstone’s legacy.

“Instead of the saintly hero of Victorian mythology, the man who speaks directly to us from the pages of his private diary is passionate, vulnerable and deeply conflicted about the violent events he witnesses, his culpability and the best way to intervene — if at all,” he says.

Spectral imaging, the process used to recover Livingstone’s original text, involves illuminating the manuscript with successive wavelengths of light — starting with ultraviolet, working through the visible spectrum and ending with infrared. Processed digital images enhanced the selected text.

The scientific and technical team, led by Mike Toth of R.B. Toth Associates, an expert in technical studies of cultural objects for museums and libraries, includes Keith Knox of Eureka Imaging (Kihei, Hawaii), Roger L. Easton Jr. of the Rochester Institute of Technology (Rochester, N.Y.), Bill Christens-Barry of Equipoise Imaging LLC (Ellicott City, Md.), Ken Boydston of MegaVision Inc. (Santa Barbara, Calif.) and Doug Emery of EmeryIT (Baltimore, Md.). The Library of Congress provided invaluable support in system development and technical advice. Together, the scholars and scientists involved in this interdisciplinary project help usher in a new era of academic endeavour in which advanced imaging technology is applied to the study of 19th-century manuscripts.

Toth says, “The results of this diary project, which enhanced Livingstone’s faded handwriting and suppressed the underlying printed text, demonstrate the significance of the spectral imaging process for the digital recovery of damaged and old manuscripts. By making the results available online, the project helps preserve the original diary, which is too fragile to be made available to the public.”

Analysis and images for download are available at

https://www.bbk.ac.uk/news/dr.-livingstones-lost-1871-massacre-diary-recovered.

For further information, contact:

Dr. Adrian S. Wisnicki

Project director | +44 7847 679 866 begin_of_the_skype_highlighting +44 7847 679 866 end_of_the_skype_highlighting (Oct. 30– to Nov. 9)

At all other times: +1 724-762-1242 begin_of_the_skype_highlighting +1 724-762-1242 end_of_the_skype_highlighting | awisnicki@yahoo.com

Mike Toth

Project program manager and president and chief technology officer of R. B. Toth Associates

+1 202-316-3993 begin_of_the_skype_highlighting +1 202-316-3993 end_of_the_skype_highlighting | mbt.rbtoth@gmail.com

Brett Bobley

Director of the Office of Digital Humanities, National Endowment for the Humanities

+1 202-606-8401 begin_of_the_skype_highlighting +1 202-606-8401 end_of_the_skype_highlighting | BBobley@neh.gov

Dawn Setzer

UCLA Library Program director of communications

+1 310-825-0746 begin_of_the_skype_highlighting +1 310-825-0746 end_of_the_skype_highlighting | dsetzer@library.ucla.edu

– The post is written by Dawn Setzer

*Source: University of California (Published on Nov. 01, 2011)