Everyone has a genetic story.

For artist Geraldine Ondrizek, an art professor at Portland’s Reed College, her story begins with the tragic loss of her child to a condition caused by a genetic anomaly. It’s a story that starts with her efforts to piece together her family’s genetic history and that has brought her, in the years since, to a beautiful intersection of science and art that today defines the very essence of her work.

Since 2001, Ondrizek has worked with geneticists and biologists to gather images of human cellular tissue and genetic tests relating to disease, ethnic identity, and the depiction of genetically inherited conditions.

“She creates wonderfully rich collaborations with scientists, taking their work and running it through her poetic filter,” explains Genevieve Gaiser Tremblay. She met Ondrizek when both were fine art students at Carnegie Mellon University and today is the curator of Ondrizek’s current exhibit, “Chromosome Painting,” on display at the Kirkland Arts Center through July 6, 2012. “Chromosome Painting” presents work generated from Ondrizek’s two-year collaboration with Robin Bennett, a UW Medicine senior genetic counselor and co-director of the UW Genetic Medicine Clinic.

In the exhibit’s three bodies of work – “Chromosome Paintings,” “DNA Microarray” and “Chromosome 17″– Ondrizek meshes her chosen medium of cloth with the colorful and complex language of genetic data to create textile portraits of human chromosome maps. Her color patterns and sequences metaphorically portray what she calls “our coats of many colors.” “Chromosome Paintings” is based on a “synteny map” that compares gene sequences and chromosomes between species. The long silk panels, each printed with human chromosome maps, are displayed in bright fluorescent colors from chartreuse and fuchsia to oranges, greens and soft blues. All are arranged to depict stunningly visual chromosomal comparisons. Each panel is labeled with a type of cancer correlated with a genetic marker present on the chromosome.

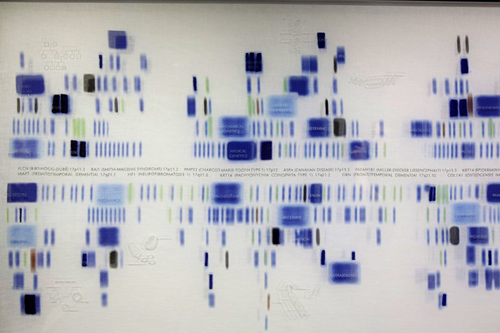

Chromosome 17, by Geraldine Ondrizek, 2011, was commissioned by the UW Division of Medical Genetics and is made of dyed and embroidered silk and engraved plexiglass. Image credit: University of Washington

“Chromosome Light Boxes” showcases each chromosome synteny map printed on white silk within a light box so the colors glow from within. These panels also are marked with the genetic anomalies linked to different types of cancer found on each gene. “DNA Micro-array” is formed from several large silk panels imprinted with small chunks of DNA sequences known as “probes” that identify target sequences of DNA and are easily seen as red, yellow, green and blue dots. And “Chromosome 17” is Ondrizek’s prototype for her 2011 UW Medical Center public art commissioned piece that today hangs in its lobby in commemoration of 50 years of medical genetics at UW Medicine.

“Genetics touches all of us,” Bennett explains. As a genetic counselor, she works closely with patients and families who are concerned about inherited diseases or conditions, and are seeking counsel about genetic testing and possible preventative action against disease.

“Learning about family medical history in conjunction with genetic testing can provide important information at many times throughout the lifespan,” Bennett said. “This collaboration shows the beauty in our DNA and brings this art and genetic science to the public, so we can have a dialogue to help allay fears and misconceptions related to genetics.”

Robin Bennett, UW Genetic Medicine Clinic co-director, wears a Chromosome 17 silk scarf in front of the Chromosome Painting studio installation by Geraldine Ondrizek, 2012. . Image credit: University of Washington

It all began in 2009, when Bennett, Ondrizek and Tremblay first collaborated on their shared vision of art and medical science – just as the UW Genetic Medicine Clinic was gearing up to celebrate its 50th anniversary. Tremblay introduced Ondrizek to Bennett and her team of renowned genetic researchers at UW Medicine, including Dr. Arno Motulsky, a pioneer medical geneticist known as one of the fathers of modern human genetics, who founded the Division of Medical Genetics at UW in 1956. The access that Bennett provided to her team of researchers inspired Ondrizek to assemble a rich collection of images from several prominent UW Medicine researchers, including Motulsky and his work on the molecular genetics of human color vision, and Dr. Peter Byers and his research into inherited connective tissue disorders.

The result was her UW Medical Center public art commissioned piece, “Chromosome 17.” In both “Chromosome 17” and “Case Study,” a piece she created for the Portland Art Museum that is also part of the Kirkland Arts Center exhibit, Ondrizek used the National Center for Biotechnical Information database of the human genome as a resource to artistically map the gene sequences.

The silk panels of the “Chromosome Painting” exhibit were also produced in a small edition of 10 each of Chromosomes 1 to 23 and will be sold as scarves to raise funds for the UW Genetic Medicine Clinic for education and research, and specifically for those who have cancer and are unable to afford medical diagnosis and treatment. Funds will also benefit cancer patients who want to preserve their DNA so their families might benefit from future genetic testing. In addition, Tremblay recently received a 4Culture Independent Artist grant that will fund her public scholarship forums: “Genetic Portraits,” a teaching artist workshop, and “Genetic Visibility,” an interdisciplinary community forum exploring issues around genetic research, family histories and genetic banking.

Overview of the Chromosome Painting studio installation, by Geraldine Ondrizek, 2012. . Image credit: University of Washington

Ondrizek received her Master of Fine Arts degree from the UW School of Art in 1994. Since 2001, she has worked with geneticists and biologists to gather images of human cellular tissue and genetic tests relating to disease, ethnic identity, and the depiction of genetically inherited conditions.

Through her artistic vision of creating a beautiful representation to help make genetic information more understandable and accessible, Ondrizek’s current exhibit presents captivating new works that showcase visual, scientific and metaphorical discoveries.

“I’m tracing my own medical history, in effect,” she said, “and it’s challenging, given the fear and misunderstandings people have around genetic science. But I saw this as an entry point for people to start thinking about – and talking about – information that is sometimes hard to swallow. It’s ultimately about all of our life connections.”

– By Clare LaFond

*Source: University of Washington