*The U’s active learning biology courses garner attention*

What if you could remove lead from a person’s blood with a bacterial protein that snags the toxic metal?

Or treat spinal cord injury by shutting off a gene that prevents nerve regrowth?

Ideas like these used to be the exclusive province of practicing biologists. But they are among 14 ideas conceived and presented recently by students in the University of Minnesota’s introductory biology course.

Who are, in a real sense, practicing biologists.

Students in the Nature of Life program visit the Mississippi headwaters, just a stone's throw from the University's Itasca Biological Station and Laboratories. Image credit: University of Minnesota

For the past five years, the U’s College of Biological Sciences (CBS) has followed the radical path of teaching not just biology, but how to be a biologist. It’s an “active learning” approach that exercises the brain cells involved in putting knowledge to work, not just storing it. And it’s catching on around the country.

It begins with Nature of Life, an intensive, three-day introduction to biology for incoming freshmen, held in summer at the U’s Itasca Biological Station and Laboratories. It continues with Foundations of Biology, a 12-credit sequence that has students work in teams, just as actual scientists do.

In the first semester, teams suggest research projects that address real problems. For example, this fall an Iraqi War veteran inspired one team to wrestle with the issue of lead poisoning, which can happen when a bullet is inoperable and lead leaches out. The team responded by designing the project described at the top of this article.

In the second semester, teams get into laboratories and work on different aspects of a broad topic. Sometimes, they come up with discoveries on a par with the pros.

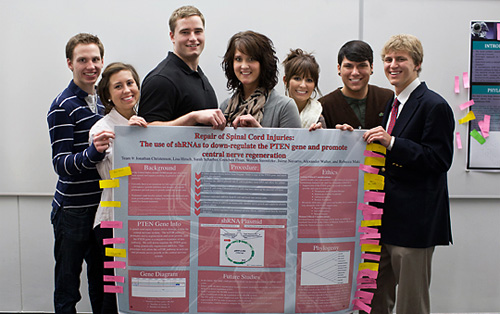

Pink slips are good. A Foundations of Biology team with a display of their idea to treat spinal cord injury by turning off a gene that inhibits nerve regrowth. The pink slips are votes of “best idea” from their peers on 13 other teams. L to r: Alex Walter, Lisa Hirsch, Jonathan Christenson, Gretchen Floan, Becky Maki, Jamie Navarro, and Weston Sternitzke. Photo: David Mendolia

“For example, students discovered that in a certain fungal lineage, the ability to survive cold evolved several times,” says Robin Wright, the professor who originated the approach. “It looks as though the trait requires multiple independent mutations. It’s very mysterious.”

“It really makes you think and come to conclusions on your own, rather than just being spoon fed the answers by the professor,” says current Foundations student Jonathan Christenson. Or, as Wright puts it, “The idea is to be on the field, not in the stands.”

Sharing the wealth

Wright finds herself in high demand these days as other universities seek to emulate the U of M students’ success. A few cases in point:

• The University of Wisconsin/Madison and Michigan State University have modeled programs after Nature of Life, focusing on at-risk students.

* Yale has expressed interest in the Foundations model.

• Wright has spoken, or will speak, at the universities of Florida, Cincinnati, and Oklahoma. The biology program has also drawn visitors from Cairo, Egypt; McGill University, and Baylor University.

“A colleague of mine at UC Davis called us ‘the best place’ for biology education,” Wright notes.

Worth the effort

Why so many schools are looking to the U of M is apparent in student performances.

“Evolutionary biology is a struggle for some students because their high schools may have taught the subject spottily,” says Mark Decker, another instructor. But when Montana State gave students from 13 schools a questionnaire about how natural selection operates, U of M students showed the greatest gain, he says.

In the Foundations courses, students sit at round tables and discuss concepts, even taking quizzes together. Once, two students confided to their instructors their fears of being overshadowed by teammates.

“Robin and I will sit down with a team like that and explain that [the team approach] means ‘nobody progresses unless you all progress,'” Decker says. “The quicker learners become teachers.”

Fears that the quicker students would be held back also failed to materialize, in part because those students became de facto teachers.

“[Data show] that all students benefit, but the higher-achieving ones benefit the most,” says Decker. “To really learn it, teach it.”

“What I came to really appreciate about Foundations of Biology was how interactive and mentally stimulating it was to go to class,” says Gretchen Floan, another current Foundations student. “It was my earliest class, at 8 a.m., but I can honestly say I never once had trouble staying awake during it.”

When a freshman says that, you know you’re doing something right.

– By Deane Morrison

*Source: University of Minnesota