Large wildlife die-off events are fairly common, though they should never be ignored, according to the U.S. Geological Survey scientists whose preliminary tests showed that the bird deaths in Arkansas on New Year’s Eve and those in Louisiana were caused by impact trauma.

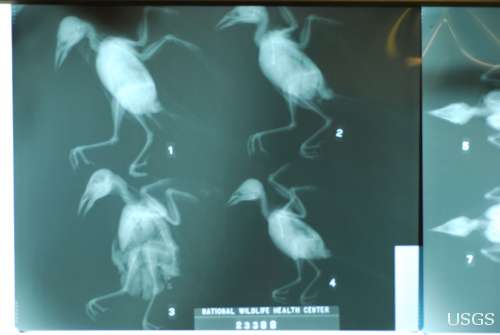

Preliminary findings from the USGS National Wildlife Health Center’s Arkansas bird analyses suggest that the birds died from impact trauma, and these findings are consistent with the Arkansas Game and Fish Commission’s statement. The State concluded that such trauma was probably a result of the birds being startled by loud noises on the night of Dec. 31, arousing them and causing them to fly into objects such as houses or trees. Scientists at the USGS NWHC performed necropsies—the animal version of an autopsy—on the birds and found internal hemorrhaging, while the pesticide tests they conducted were negative. Results from further laboratory tests are expected to be completed in 2-3 weeks.

“Although wildlife die-offs always pose a concern, they are not all that unusual,” said Jonathan Sleeman, director of the USGS NWHC in Madison, Wis., which is completing its analyses of the Arkansas and Louisiana birds. “It’s important to study and understand what happened in order to determine if we can prevent mortality events from happening again.”

The carcass of a red-winged blackbird from Beebe, AR is being examined by USGS National Wildlife Health Center wildlife pathologist Dr. David E. Green. Image credit: Allison Klein, U.S. Geological Survey

In 2010, the USGS NWHC documented eight die-off events of 1,000 or more birds. The causes: starvation, avian cholera, Newcastle disease and parasites, according to Sleeman. Such records show that, while the causes of death may vary, events like the red-winged blackbird die-off in Beebe, Ark., and the smaller one near Baton Rouge, La., are more common than people may realize.

And Sleeman should know – he directs a staff of scientists whose primary purpose is to investigate the nation’s wildlife diseases from avian influenza to plague and white-nose syndrome in bats.

The carcass of a red-winged blackbird from Beebe, AR is being examined by USGS National Wildlife Health Center wildlife pathologist Dr. David E. Green. Image credit: Allison Klein, U.S. Geological Survey

“The USGS NWHC provides information, technical assistance, research, education, and leadership on national and international wildlife health issues,” Sleeman added.

According to USGS NWHC records, there have been 188 mortality events across the country involving 1,000 birds or more during the past 10 years (2000 – 2010). In 2009, individual events included one in which 50,000 birds died from avian botulism in Utah; 20,000 from the same disease in Idaho; and 10,000 bird deaths in Washington from a harmful algal bloom.

The carcass of a red-winged blackbird from Beebe, AR is being examined by USGS National Wildlife Health Center wildlife pathologist Dr. David E. Green. Image credit: Allison Klein, U.S. Geological Survey

Mass mortality events occur in other animal populations as well, according to the USGS NWHC. For example, prairie dog colonies in the West can be destroyed by sylvatic plague, which can then kill off the highly endangered black-footed ferret that preys on prairie dogs exclusively. The USGS NWHC is involved with developing vaccines, delivered through bait, which can immunize prairie dogs against plague.

In the 1970’s and 1980’s, most USGS NWHC die-off investigations involved large numbers of waterfowl deaths from avian cholera, avian botulism, and lead poisoning; in the 1990’s, the USGS NWHC was highly involved in investigating the emergence of West Nile virus in North America. In 2008, the USGS NWHC discovered the cause of white-nose syndrome, a fungal disease that has devastated cave hibernating bat species in the Northeastern U.S.

Public reporting of wildlife mortality events is important, and in 2010, the USGS Wildlife Disease Information Node initiated an experimental reporting system to facilitate this. Visit https://www.whmn.org/wher/ for more information.

More information on the USGS NWHC and its involvement in the recent bird die-off events can be found on the NWHC web site.

*Source: U.S. Geological Survey