It may take years before scientists determine the full impact of the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico. But, utilizing the human-occupied submersible Alvin and the autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV) Sentry, researchers are about to investigate—and view first-hand—the possible effects of the spill at the bottom of the Gulf.

And, from Dec. 6-14, the mission will be relayed to the public as it happens on the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution’s (WHOI) Dive and Discover website (https://divediscover.whoi.edu).

Scientists from numerous institutions—led by Penn State University, Temple University, Haverford College, and WHOI—will probe the depths of the Gulf to look for any impact on the organisms that inhabit deep-ocean communities.

To accomplish this, they will employ two undersea vehicles of the US’s National Deep Submergence Facility that is operated by WHOI. The expedition, aboard the R/V Atlantis, will feature six dives using Alvin to document the ocean bottom and collect samples of animals and sediment. Working in concert, Sentry will carry out overnight missions to map and photograph the bottom to pave the way for each successive Alvin dive.

Alvin is loaded onto the R/V Atlantis on WHOI dock. Image credit: Tom Kleindinst, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

The first dive site will likely be the location where a preceding expedition that ended in early November found signs of dead and dying corals near the Macondo 252 well, which blew out on April 20 and continued to pour oil into the Gulf for 86 days. That mission featured the remotely operated vehicle (ROV) Jason and many of the same scientists on the upcoming cruise, including Chief Scientist Charles Fisher of Penn State University and co-investigators Erik Cordes of Temple and Tim Shank of WHOI; Chris German of WHOI also will be a co-investigator on next week’s Gulf cruise. The Jason investigation discovered dozens of the corals just seven miles from the Macondo well. With Alvin and Sentry working in tandem, this current team will revisit that site as well as seek out unexplored places on the ocean floor to learn whether the oil spill did, in fact, affect animals there.

Sentry will be used to map the seafloor with high-resolution sonar to direct Alvin to sites never visited before. This will be the first dual use of an AUV and manned submersible in the Gulf since the blowout, greatly enhancing Alvin’s effectiveness.

The cruise will also attempt to retrieve samples collected by autonomous sediment traps deployed in June. These complement similar instruments put in place from September 2009 until this June, thus creating a time-series of samples that will help reveal how oil and dispersants affected the material that settles to the bottom from the upper- and mid-ocean.

Alvin is doing a quick turnaround from its first foray into the post-spill Gulf of Mexico. Since Nov. 8, it has been exploring the Gulf on a cruise under the direction of Chief Scientist Samantha Joye from the University of Georgia. During that time Alvin has been involved in collecting sediment and water column samples from the vicinity of the Deep Horizon wellhead.

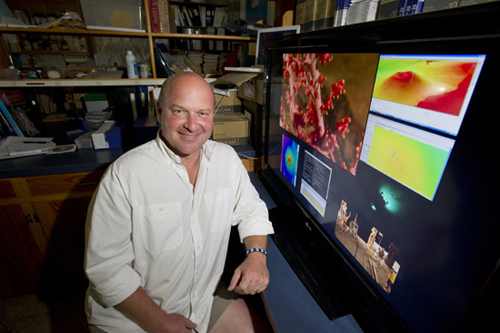

Tim Shank of WHOI will be an investigator on the Gulf Cruise. Image credit: Tom Kleindinst, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

The upcoming cruise will constitute Dive and Discover’s 13th mission, which is being funded by the National Science Foundation. The site’s first 12 expeditions, covering marine science expeditions around the world, have taken place since the site was launched in January 2000. Website visitors will be able to tag along—via their computers—and experience much of what the scientists are seeing and learning.

Dive and Discover is an interactive distance-learning website designed to immerse viewers in the excitement of discovery and exploration of the deep seafloor. The site is targeted at middle school students (Grades 6-8) and the interested public and is structured to provide multiple levels of information. The backbone of the site is a series of educational modules that address basic science concepts central to the research being conducted at sea. References and links are made throughout to provide the viewers with easy access to more detailed and related information.

The site provides daily updates of an ongoing cruise, including still and video images from the seafloor and of shipboard operations. It also displays graphical representations of a wide variety of oceanographic data, explanations about the technology being used, and general information about life at sea for the scientists, engineers, and mariners aboard. In addition, a ”Mail Buoy” allows students and others to communicate directly by email with scientists at sea.

WHOI operates Alvin for the national oceanographic community. Built in 1964 as one of the world’s first deep-ocean submersibles, Alvin has made more than 4,600 dives. It can reach nearly 63 percent of the global ocean floor.

The sub’s most famous exploits include locating a lost hydrogen bomb in the Mediterranean Sea in 1966, exploring the first known hydrothermal vent sites in the 1970s, and surveying the wreck of RMS Titanic in 1986.

Alvin carries two scientists and a pilot as deep as 4,500 meters (about three miles) and each dive lasts six to ten hours. Using six reversible thrusters, Alvin can hover, maneuver in rugged topography, or rest on the sea floor. Diving and surfacing is done by simple gravity and buoyancy—water ballast and expendable steel weights sink the sub, and that extra weight is dropped when the researchers need to rise back up to the surface.

The sub is equipped with still and video cameras, and scientists can also view the environment through three viewports. Because there is no light in the deep, the submersible carries quartz iodide and metal halide lights to illuminate the seafloor. Alvin has two robotic arms that can manipulate instruments, and its basket can carry up to 200 pounds of tools and seafloor samples.

This will be Alvin’s last mission before it undergoes a major upgrade in 2011 that includes the installation of a new personnel sphere to give pilots and scientists more room and redesigned portals to provide bigger viewports with overlapping fields of view.

Sentry was crucial in a June expedition in which WHOI scientists detected and characterized a plume of hydrocarbons at least 22 miles long and more than 3,000 feet below the surface of the Gulf of Mexico, a residue of the BP Deepwater Horizon spill.

The WHOI team based its findings on some 57,000 discrete chemical analyses measured in real time. They accomplished their feat using Sentry and a type of underwater mass spectrometer known as TETHYS (Tethered Yearlong Spectrometer), also developed at WHOI.

Sentry can survey large areas of the sea floor on dives lasting a day or more without requiring that someone watch its every move. This is important when the job requires a long series of difficult or repetitive tasks that would be difficult and expensive to do with remotely operated or manned vehicles or that would very quickly become monotonous or overwhelming for a human to do manually. On a recent cruise to the Galapagos Rift, Sentry mapped about 100 square kilometers (40 square miles) of the seafloor to a resolution of 1 meter (3 feet).

*Source: Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI)