Scientists have discovered a physiological chain of events in animal models in which motor neurons and their communication with muscle become disrupted by the mutation that causes spinal muscular atrophy.

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Though spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) in its most severe form remains incurable and fatal in early childhood, researchers are sustaining a multipronged counterattack for patients and their families. The first treatment for the disease gained U.S. market approval in December. Now a new discovery led by Brown University scientists deepens the basic understanding of how the genetic mutation that causes SMA appears to undermine the communication between motor neurons and the muscles they control.

“We are making progress,” said Anne Hart, professor of neuroscience at Brown and senior author of the new study in the journal eLife.

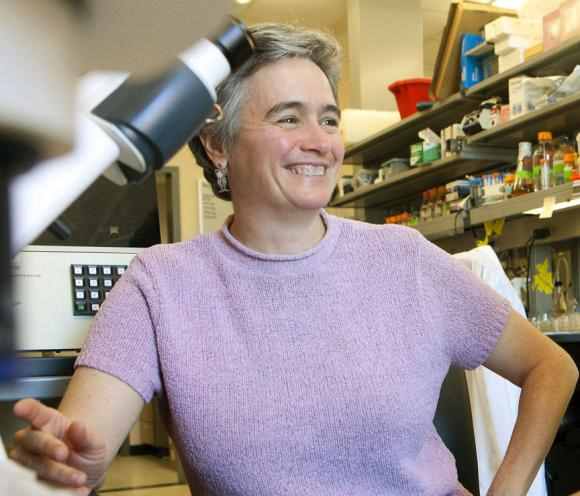

In a new study, researchers led by neuroscience Professor Anne Hart describe a complex cause-and-effect sequence that might underlie some of the problems seen in spinal muscular atrophy. Image credit: Brown University

About one in 8,000 children is born with some form of SMA in which mutations in both copies of the gene that code for the survival motor neuron (SMN) protein cripples its production. The end result, which the new study helps to explain, is dysfunction of motor neurons that control muscle along with muscle atrophy and weakness. In the most acute form, Type I, children die by age two as even functions as fundamental as breathing become compromised. With other SMA types patients can live much longer, but they still suffer significant muscle weakness.

Revealing and targeting the “how”

It’s a positive sign that spinal cord injections of nusinersen, the newly approved drug, restore some motor function and prolong survival by improving SMN production, Hart said, but researchers can make further and perhaps more lasting headway by understanding how the lack of SMN ultimately undermines muscle function.

“If we can figure out what is going wrong, then maybe we can have combinatorial therapies — one that raises SMN levels and one that helps neurons survive the challenge of too little SMN,” Hart said.

Last year her lab published evidence that one mechanistic consequence of the disease is a disruption of the process by which neurons can recycle and reuse proteins needed for neural control of muscle.

Experiments described in the new study identify another mechanism. Led by graduate student Patrick O’Hern, the team at Brown and the University of Cologne in Germany uncovered a complex cause-and-effect sequence in both C. elegans worm and mouse models of SMA. A lack of SMN hinders the working of a protein called Gemin3. That, in turn, lessens the activity of a particular microRNA, which turns out to be needed to prevent the overexpression of a motor neuron receptor called m2R.

The role of those receptors is to sense when the neuron has released enough of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine to signal a muscle cell to move. With too many m2R receptors because of their overexpression in SMA, Hart said, motor neurons may be too sensitive to their acetylcholine output and consequently shut off its release prematurely. That may be severely undermining the effectiveness of the motor neuron signal and therefore proper muscle function.

The link between the disease and the regulation of protein translation that microRNA provides was the Gemin3 protein, Hart said. O’Hern had noticed that in some studies Gemin3 interacted with SMN and in other studies it was wrapped up in a complex of proteins that interact with microRNA.

“He pulled those ideas together and said what if loss of SMN perturbs Gemin3 and that has consequences for the microRNAs,” Hart said.

O’Hern and the team not only traced this whole mechanism, but also they showed that they could address it at several stages along the way, restoring healthy neuron development and muscle function in the worms. In lab tests in Cologne with mouse motor neurons, moreover, they found that when they added the m2R-blocking drug methoctramine, they could restore crucial benchmarks of motor neuron function and health.

The m2R receptors therefore are a new potential target for treating the disease, Hart said. But only more work will tell whether that’s true for more than just in worms and mouse tissue.

“If you decrease the activity of these receptors, it could be beneficial,” she said. “This needs to be tried in other models, too.”

In addition to O’Hern and Hart, the paper’s other authors are Eduardo Javier Lopez Soto, Jonah Simon, Natalie Chapkis and Diane Lipscombe of Brown University and Ines do Carmo Goncalves, Johanna Brecht and Min Jeong Kye of the University of Cologne.

The SMA Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, Cure SMA and Deutsche Forschungsgemeineschaft funded the research.

By David Orenstein

*Source: Brown University