Erin Diamond shines as a brain researcher

In October 2010 freshman Erin Diamond first walked into Yang Zhang’s lab, knowing nothing about his specialty: brain imaging.

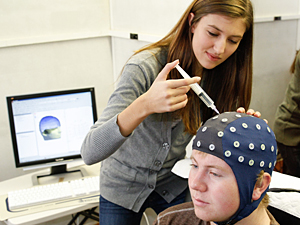

Before the day was out, she was setting up experiments, putting an EEG cap on volunteers, and generally undergoing total immersion in the field.

A Freshman Research and Creative Awards Program scholarship from the College of Liberal Arts (CLA) allowed Diamond to join Zhang’s lab. While conducting research there, she learned MRI and other sophisticated techniques to study how the human brain works.

Her future in Zhang’s lab was already in the works when the scholarship came.

“I had a course with Dr. Zhang, and I’d seen his research on his website and thought it was fascinating,” says Diamond. “A few weeks later, he needed an undergraduate research assistant and asked me to apply.”

Diamond’s work with Zhang—and, more recently, Benjamin Munson—in CLA’s Department of Speech-Language-Hearing Sciences has made her a seasoned researcher aiming for a career as a speech-language pathologist. She graduates from the University of Minnesota this spring.

When eyes and ears disagree

As a UROP student with Zhang, Diamond studied how the brain reacts to conflicting information from sound and emotional cues.

For example, volunteers were shown pictures of faces whose mouths were shaped to make either an “ee” or an “ah” vowel. Then they heard “bob” or “beeb,” which either matched or conflicted with the mouth shape. She also studied how brains responded when pictures of angry or happy faces were paired with angry- or happy-sounding words, again in either matching or conflicting combinations.

With EEG, Diamond recorded which parts of the brain responded differently to matched and mismatched cues—an indication that mismatches were detected. She found that mostly the right half of the cerebrum responded to emotional mismatches, while the left half responded to phonetic mismatches.

This kind of research can be used to show how typical and atypical brains respond to different kinds of information, she says.

“Having this kind of data with, for example, autistic children might show that their brain’s response to emotional cues is different from typical kids’,” says Diamond. “It lays a theoretical foundation for therapy down the line.”

Zhang has nothing but praise for Diamond’s knack for research.

“I was greatly impressed by her … eagerness to acquire not only theoretical knowledge but also the necessary laboratory skills to conduct studies as a researcher,” he says. “She is very patient with the [volunteers] and meticulous about the details. For example, she spotted a couple of minor mistakes and typos in one of my manuscripts under preparation for journal submission.”

Speaking of speaking

Also with Zhang, Diamond took part in studies of how native English speakers and Chinese [Mandarin] speakers learning English processed English grammar and meaning. For example, with sentences like ‘I have two hand,’ the brains of native speakers showed a much clearer and stronger response to the error than brains of Chinese speakers.

“I’m interested in all aspects of bilingualism, but mostly people who are deeply bilingual,” says Diamond. “If we have, for example, a stroke victim who speaks Spanish at home and English at work, we have to understand how the two languages work to provide better interventions. We have to understand how the brain organizes languages.”

*Source: University of Minnesota