A three-minute cartoon video made by two UA graduate students is one of 10 finalists in the Ocean 180 Video Challenge, an outreach campaign designed to inspire scientists to communicate the meaning and significance of scientific research to a broader audience.

A science video disguised as a cartoon murder mystery has landed two University of Arizona marine ecology students among the top 10 finalists in the Ocean 180 Video Challenge, an outreach campaign designed to inspire scientists to communicate the meaning and significance of scientific research to a broader audience.

The campaign is sponsored by the Florida Center for Ocean Science Education Excellence and funded through a grant from the National Science Foundation.

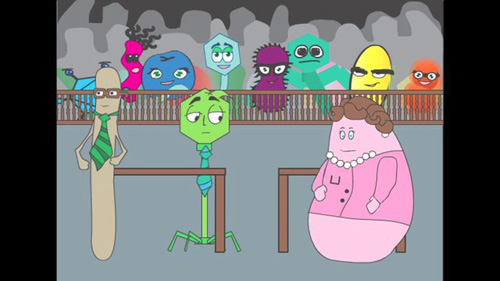

In the video, cartoon characters playing parts in a murder trial portray microbes and viruses fighting for survival in the ocean. Image credit: University of Arizona

Recognizing the need for scientists to communicate more effectively with the general public, the inaugural Ocean 180 Video Challenge asked ocean scientists to explain their research to middle school students.

Sound easy? How about in 180 seconds or less?

Scientists from across the country took on the challenge, sharing their recently published research in three-minute video clips. The top 10 submissions were selected by a panel of science and communication experts. Now the finalists will be evaluated by middle school students, arguably one of the most critical audiences.

Ann Gregory, a doctoral student in soil, water and environmental Science at the UA College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, and J. Cesar Ignacio Espinoza, a doctoral student in the molecular and cellular biology program at the UA College of Science received an email from their adviser, Matt Sullivan, about the competition. Sullivan is a professor in the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology and heads the Tucson Marine Phage Lab, a bustling research group specializing in discovering the hidden world of viruses that drift through the world’s oceans and the microbes on which they prey.

Doctoral student J. Cesar Ignacio Espinoza studying water samples in the lab aboard a research vessel in the Mediterranean Sea. (Photo by: Matt Knatz)

“We thought that it would be a great opportunity to share our research with a broader audience,” Gregory said. “Since microbes are usually negatively portrayed in the media, we wanted to highlight microbes in a fun light. Plus, everybody loves a crime story.”

“Marine cyanobacteria of the genera Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus are abundant in the ocean, and they are responsible for the generation of up to one-third of the oxygen in our planet’s atmosphere,” Espinoza said. “The Sullivan lab recently developed a technique called viral tagging; this technique helps to identify the viruses that infect different cyanobacteria in a very specific manner.”

And so Gregory and Espinoza spent four weekends creating a lighthearted story featuring various microbes and viruses as cartoon characters. Their video, “Innocence by Viral Tagging,” is based on research published by the Sullivan lab.

Bacteriophages come in different shapes and sizes. This one has a “head” containing the virus’ DNA and a “tail” with which it attaches to bacterial cells when it infects them. The scale bar in this electron microscope image is about one-thousandth the diameter of a human hair. (Photo by: Natalie Solonenko)

Marine bacteria account for many of the microorganisms that make up marine and freshwater phytoplankton, where they control global cycles of oxygen and carbon, and their boom and bust cycles directly translate into abundance and shortage of nutrients, which sustain global food webs and fisheries, for example. The hidden movers and shakers behind these processes are the viruses called bacteriophages that infect their bacterial hosts, regulating their populations and swapping genetic material among them. By understanding the viruses, scientists can develop models that can help better explain the consequences of processes ranging from algae blooms to fish stock assessments to carbon storage in the world’s oceans.

“In our movie, an unknown virus kills a very wealthy cyanobacterium, Mr. Prochlorococcus,” Espinoza explained. “While visual accounts link Myo Cyanophage – a virus – to the crime, he is exonerated thanks to the use of the viral-tagging technique. The viral-tagging experiment did not find a link between Myo cyanophage and Mr. Prochlorococcus.

Throughout January, more than 1,800 middle school classrooms with more than 42,000 students in sixth, seventh and eighth grade from all 50 U.S. states and 13 countries will screen the videos and evaluate the communication skills of the ocean scientists who submitted them. These students are responsible for not only selecting the winners, but providing feedback and comments to the scientist. The opinions of the student judging team are taken very seriously, with the three winners of the Ocean 180 Video Challenge receiving up to $6,000 in cash prizes.

Sullivan said: “This Oceans180 Challenge is an exciting way to let students consider creative new ways to communicate their science. In our case, Ann and Cesar involved the whole lab with a script they’d written where each of us read our own voice-over parts. It was a very clever and fun project for them!”

Of the 480 teachers who have registered their classrooms as student judges, many are looking for a way to inspire students to view science as a potential career, not just a subject in school.

“Ocean scientists who submitted films will ultimately have tens of thousands of students, some potential scientists, learning about their research,” said Mallory Watson, COSEE Florida Scientist and member of the organizing committee for Ocean 180. “Just as important, evaluations from students will be used to help scientists be better equipped to engage the general public in ocean science research.”

While registered middle school classrooms are participating as judges, the videos are available to the public. Visit the campaign website for a list of team members, participating classrooms and to view the finalists’ videos. Winners will be announced in late February.

– By Daniel Stolte

*Source: The University of Arizona