Friends may help reduce package delivery costs

Every day trucks ply the neighborhoods of America, driving “the last mile” of the delivery chain for goods ordered through Amazon, eBay, and other online retailers.

But this last mile produces about half the fossil fuel consumption and emissions of the total retail system, according to studies.

What if somebody designed a system of drop-off points where people who regularly pass nearby could pick up packages for friends?

“If we had a socially networked distribution system, we could reduce travel miles by 30 to 95 percent, depending on the degree to which your network participated,” says University of Minnesota researcher Tim Smith, an associate professor in the Department of Bioproducts & Biosystems Engineering, who recently led a study that modeled such systems.

The study was published online August 9 in the Journal of Environmental Science and Technology.

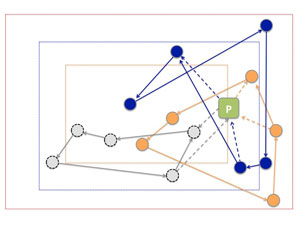

Schematic of three people’s daily driving routes and a centralized pickup point. Dotted lines represent detour paths for pickups. Image credit: University of Minnesota

Moves in this direction are already being made. Both Amazon and Google have introduced package delivery lockers that allow online shoppers to have packages sent to a centralized location for pickup, Smith notes. Amazon launched its delivery lockers earlier this year and plans to expand the program to place lockers in retail stores, most notably Staples Inc., the largest U.S. office supply retailer.

While these lockers are largely promoted to business customers seeking options for after-hours delivery, they also have been able to cut delivery times at lower costs.

“In Seoul, South Korea, it’s possible to order online and have it delivered to your home in a few days for a certain price,” says Smith. “Or, for a lower price you can pick it up at a kiosk on the subway platform and have it in a matter of hours.”

Online shopping requires a lot of deliveries. In the United States, it’s estimated that up to 40 percent of households order online every week, Smith says.

Location matters

In their study, Smith and his colleagues modeled the efficiency of delivery to a centralized pickup location, like a grocery store or gas station, in urban and suburban areas. Modeling urban Minneapolis, the system worked well: Compared to the current system, travel miles dropped by 3 percent, greenhouse gas emissions by 21 percent.

Tim Smith is director of the NorthStar Initiative for Sustainable Enterprise in the University of Minnesota’s Institute on the Environment. Image credit: University of Minnesota

Modeling suburban Woodbury, Minnesota, however, the system failed: travel miles went up by 27 percent and greenhouse gas emissions barely budged (because personal vehicles consume less fuel than delivery trucks). Trouble is, many more individual vehicles have to drive too far out of their way to get to their packages. And, says Smith, “it may be quite difficult to get the right number and right locations for pickups throughout sparsely populated and sprawling suburbs.”

But when they modeled urban and suburban environments assuming a social network where people could collect packages for friends, the efficiencies improved dramatically for both areas. “By putting a social network to work, there is a very good chance that a close friend will come much closer to the pickup location than the actual customer,” Smith says.

Technologies such as RFID (radio frequency ID) tags on packages that could talk to smart phones owned by friends in the network could be key.

“For example, you may be driving home, and your phone beeps, saying you’re 100 yards from a predetermined friend’s package and asking if you’ll pick it up for them,” says Smith. If so, the handoff could happen at work, in the neighborhood, in the gym, or at another pickup location along the friend’s normal route home from work. If not, recipients can always pick up packages themselves.

“Our research suggests that with only one to five percent of the delivery network participating, very large efficiencies can be gained,” Smith notes.

Details, details

The actual costs of online package delivery are hard to estimate, but assuming an average cost of two-day delivery at $10, local delivery might account for $4 or $5, and $3 or $4 might be saved by socially networked delivery. Where would the savings go?

That’s one of many details that would have to be ironed out, Smith says. Some savings might go to the online retailer, to the online customer, or for space rental at the host pickup location; some could also be shared as an incentive for friends to pick up packages. It’s unknown whether 50 cents or a dollar would motivate friendly pickup, but real money is at stake here.

“Cyber Monday—the online holiday shopping equivalent of ‘Black Friday’—alone generated nearly $2 billion in sales and nearly 11 million orders this year, according to industry reports,” says Smith.

“Our research identifies areas of efficiencies and inefficiencies associated with the thorny problem of the last mile of distribution. The new competition over the delivery locker market from the online giants suggests there might be something to these types of delivery systems. We’ll have to wait and see if a business model emerges to extend the service to a social network.”

*Source: University of Minnesota