Like a self-absorbed teenager, insects spend a lot of time grooming.

In a study that delves into the mechanisms behind this common function, North Carolina State University researchers show that insect grooming – specifically, antennal cleaning – removes both environmental pollutants and chemicals produced by the insects themselves.

The findings, published online this week in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, show that grooming helps insects maintain acute olfactory senses that are responsible for a host of functions, including finding food, sensing danger and even locating a suitable mate.

The findings could also explain why certain types of insecticides work more effectively than others.

Insects groom themselves incessantly, so NC State entomologist Coby Schal and post-doctoral researchers Katalin Boroczky and Ayako Wada-Katsumata wanted to explore the functions of this behavior.

They devised a simple set of experiments to figure out what sort of material insects were cleaning off their antennae, where this material was coming from, and the differences between how groomed and ungroomed antennae functioned. Schal likened the straightforwardness of some of the experiments to something you’d see in a well-equipped high-school science lab.

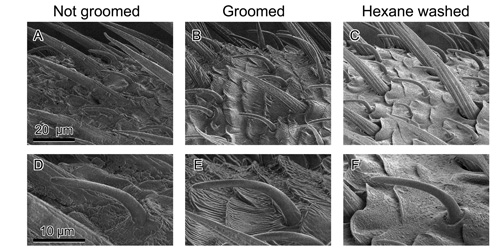

Electron microscopy images show ungroomed, groomed and cleansed roach antennae (A-C). Also shown are tiny, pheromone-sensitive sensilla on the antennae (D-F). Image credit: North Carolina State University

The researchers compared cleaned antennae of American cockroaches with antennae that were experimentally prevented from being cleaned. They found that grooming cleaned microscopic pores on the antennae that serve as conduits through which chemicals travel to reach sensory receptors for olfaction. Cockroaches clean their antennae by using forelegs to place the antennae in their mouths; they then methodically clean every segment of the antenna from base to tip.

The researchers found that both volatile and non-volatile chemicals accumulated on the ungroomed antennae of cockroaches, but most surprising was the accumulation of a great deal of cuticular hydrocarbons – fatty, candlewax-like substances secreted by the roaches to protect them against water loss.

“It is intuitive that insects remove foreign substances from their antennae, but it’s not necessarily intuitive that they groom to remove their ‘own’ substances,” Schal says.

The researchers also tested groomed and ungroomed cockroach antennae to gauge how well roaches picked up the scent of a known sex pheromone compound, as well as other odorants. Clean antennae responded to these signals much more readily than ungroomed antennae.

The researchers then put carpenter ants, houseflies and German cockroaches to many of the same tests. Although they groom a bit differently than cockroaches – flies and ants seem to rub their legs over their antennae to remove particulates, with ants then ingesting the material off their legs – the tests showed that these insects also accumulated more cuticular hydrocarbons when antennae went ungroomed.

“The evidence is strong: Grooming is necessary to keep these foreign and native substances at a particular level,” Schal says. “Leaving antennae dirty essentially blinds insects to their environment.”

Cockroaches groom their antennae by using their forelegs to place the antennae in their mouths; they then methodically clean the antennae from base to tip. Photo courtesy of Ayoko Wada-Katsumata.

Schal adds that there could be pest-control implications to the findings. An insecticide mist or dust that settles on a cockroach’s antennae, for instance, should be ingested by the roach rather quickly due to constant grooming. That method of insecticide delivery could be more effective than relying on residual insecticides to penetrate the thick cuticle, for instance.

Finally, Schal says the study can also be used as a caution to other researchers who use insects in experiments. Gluing shut an insect’s mouth to prevent it from feeding, for example, also prevents the insect from grooming its antennae. Experimental results could be skewed as a result of this sensory deprivation, Schal suggests.

Dale Batchelor, a researcher in NC State’s Analytical Instrumentation Facility, co-authored the paper, as did Marianna Zhukovskaya at the Russian Academy of Sciences. The research was supported by the National Institute of Food and Agriculture, the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the National Science Foundation and the Blanton J. Whitmire Endowment at NC State.

*Source: North Carolina State University