Scientists from the U.S. Department of Energy’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory have obtained the closest look yet of how a gargantuan molecular machine breaks down unwanted proteins in cells, a critical housekeeping chore that helps prevent diseases such as cancer.

They pieced together the molecular-scale changes the machine undergoes as it springs into action, ready to snip apart a protein.

Their work provides valuable clues as to how the molecular machine, a giant enzyme called tripeptidyl peptidase II, keeps cells tidy and disease free. It could also inform the development of obesity-fighting drugs. A closely related enzyme in the brain can cause people to feel hungry even after they eat a hearty meal.

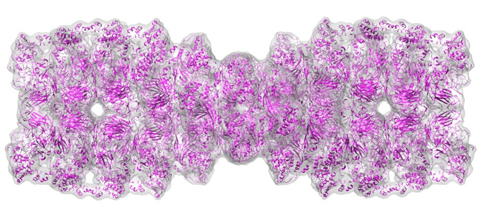

About the image: New clues emerge about how a molecular machine breaks down unwanted proteins in cells thanks to work conducted at Berkeley Lab’s Advanced Light Source. In this atomic-scale model of the molecular machine, tripeptidyl peptidase II, the cyan ribbon depicts the skeleton of the giant molecule. The grey enclosure represents the lower resolution surface and is included to aid visualization. Image credit: Berkeley Lab

Tripeptidyl peptidase II is found in all eukaryotic cells, which are cells that a have membrane-bound nucleus. Eukaryotic cells make up plants and animals. The enzyme’s chief duty is to support the pathway that ensures that cells remain healthy and clutter free by breaking down proteins that are misfolded or have outlived their usefulness.

It’s not always so helpful, however. A variation of the enzyme in the brain degrades a hormone that makes people feel satiated after a meal. When this hormone becomes unavailable, a person can eat and eat without feeling full, which can lead to obesity.

Tripeptidyl peptidase II is also the largest protein-degrading enzyme, or protease, in eukaryotic cells. It’s more than 100 times larger than most other proteases.

“We want to know how it’s regulated, how it selects proteins to degrade, and how it cuts them apart,” says Jap.

To help answer these questions, his team determined the changes the molecular machine undergoes as it readies itself for action. Using x-ray crystallography, they obtained an atomic-scale resolution structure of the molecular machine in its inactive state. This work was conducted at Berkeley Lab’s Advanced Light Source, a national user facility that generates intense x-rays to probe the fundamental properties of substances.

They then merged these two structures together, one dormant and the other ready to pounce on a protein.

This first molecular-scale vantage of the enzyme in action offers insights into how it works. For example, the scientists found that only very small proteins can fit in the chamber the enzyme uses to break down proteins.

The research was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health. The Advanced Light Source is supported by the Department of Energy’s Office of Science.

*Source: Berkeley Lab