COLLEGE PARK, Md. – A fossil leaf fragment collected decades ago on a Virginia canal bank has been identified by a University of Maryland doctoral student as one of North America’s oldest flowering plants, a 115- to 125-million-year-old species new to science. The fossil find, an ancient relative of today’s bleeding hearts, poses a new puzzle in the study of plant evolution: did Earth’s dominant group of flowering plants evolve along with its distinctive pollen? Or did pollen come later?

The find also unearths a forgotten chapter in Civil War history reminiscent of the film “Twelve Years a Slave,” but with a twist. In 1864, Union Army troops forced a group of freed slaves into involuntary labor, digging a canal along the James River at Dutch Gap, Va. The captive men’s shovels exposed the oldest flowering plant fossil beds in North America, where the new plant species was ultimately found.

University of Maryland doctoral student Nathan Jud, a paleobotanist – an expert in plant fossils and their environments – identified the species and its significance. Jud named it Potomacapnos apeleutheron – Potomacapnos for the Potomac River region where it was found, and apeleutheron, the Greek word for freedmen. A paper describing the new species was published in the December 2013 issue of the American Journal of Botany.

The compound leaves of Potomacapnos apeleutheron identify the 120 million-year-old plant fossil as the earliest known North American member of the eudicots, the largest group of flowering plants. The fossil plant, which resembles a modern bleeding heart, was found in a fossil bed at Dutch Gap, VA. Photo credit: Nathan Jud

Jud is studying the change that began 140 million years ago in the Early Cretaceous period, when plant communities of ferns gave way to a world dominated by flowering plants. In December 2011 he was at the Smithsonian Institution, where he is a pre-doctoral fellow, looking through clay-encrusted fossil ferns from Dutch Gap. Jud spotted one tiny leaf tip that seemed different.

A technician scraped away clay to reveal compound leaves, which placed the specimen in the flowering plant group known as eudicots. Today, most flowering plants are eudicots, but they were rare in the Early Cretaceous. Potomacapnos apeleutheron is the first North American eudicot ever found among geologic deposits 115 to 125 million years old.

University of Maryland paleobotanist Nathan Jud identified the fossil plant and its significance and named it in honor of the freedmen whose labor made the discovery possible. Photo courtesy of Nathan Jud

Jud consulted paleobotanist Leo J. Hickey, who collected the leaf fossil at Dutch Gap in 1974. Hickey, a former director of Yale’s Peabody Museum of Natural History, agreed the plant is an early eudicot.

One feature all eudicots share is the shape of their pollen grains, which have three pores through which the plant’s sperm cells are released. But there is no three-pored pollen in the clay where the fossil was found. That’s puzzling, Jud says, since pollen has a hard shell that preserves it in the fossil record. Scientists use pollen as a marker of geologic time and environmental conditions, so a change in the evolutionary sequence of eudicots and their pollen could have important implications for many types of analyses.

“Either the plant was very rare, and we just missed its pollen,” Jud says, “or it’s possible that eudicot leaves evolved before (three-pored) pollen did.”

Hickey was excited that the Dutch Gap find might shed light on a crucial stage in flowering plant evolution. He became a co-author of Jud’s research paper, but he died of cancer in February 2013, before the paper could be published.

It was Hickey who told Jud the history of the Dutch Gap site, where Union generals trying to capture Richmond in 1864 thought the canal would be a strategic shortcut. Hickey knew the black laborers who dug the canal were forced to work against their will, though most modern histories don’t say so.

Jud turned to Steven Miller, co-editor of the University of Maryland’s Freedmen and Southern Society Project, where researchers analyze 2 million documents about former slaves’ passage from bondage to freedom. Miller unearthed a protest letter from 45 impressed freedmen to the command of Union Gen. Benjamin Butler.

The men wrote that they were taken to Dutch Gap “at the point of the bayonet” and forced to dig for weeks without pay. When more laborers were needed “guards were then sent … to take up every man that could be found indiscriminately young and old sick and well. the soldiers broke into the coulored people’s houses taken sick men out of bed … ” A Union lieutenant endorsed the letter, writing that the men “were brought away by force” and were suffering greatly.

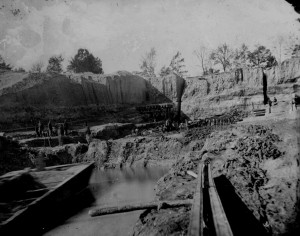

Union soldiers used trickery and force to compel freed slaves to dig a canal at Dutch Gap, VA in 1864. The freedmen’s shovels exposed the fossil bed where North America’s oldest known eudicot was found. Photo credit: Matthew Brady Collection, 1864, National Archives (Click image to enlarge)

The Union Army’s impressment of freed slaves into involuntary servitude “happened pretty regularly,” Miller says. Black soldiers served in the Union ranks, black laborers did much of the Army’s heavy work, and “for big projects like the Dutch Gap canal they would dragoon people from wherever they could get them – voluntarily if they could, and if they could not, by forced impressment.”

After visiting the site, where cobblestones top heavy clay, Jud decided to commemorate the freedmen’s “horrific” suffering in the fossil’s name. “The reason you can dig fossils there is because of what they went through,” he says. “I thought that instead of naming it after another scientist, I should name it after the people who made this discovery possible.”

*Source: University of Maryland