Hosted by world-renowned astrophotographer Adam Block at the UA’s Mount Lemmon SkyCenter, a group of sky and astronomy enthusiasts watched Venus cross the sun from the highest vantage point in Southern Arizona.

On Nov. 24, 1639, in the tiny village of Much Hoole not far from Liverpool, England, a poor farmer’s son and self-taught astronomer affixed a sheet of paper in front of a makeshift telescope pointed at the sun and waited.

Thirty-five minutes before sunset, a dark, round spot appeared right next to the bright disc that was the sun’s face projected on the paper, and made Jeremiah Horrocks, only 20 years old at the time, the first known human to predict, observe and record a transit – the passage of a planet across the sun as seen from Earth.

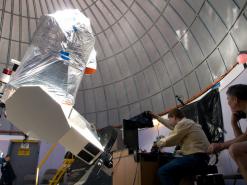

Almost 373 years later, a group of sky enthusiasts is gathered beneath the dome of one of the University of Arizona’s observatories on Mount Lemmon just north of Tucson, Ariz.

Projecting the Sun's image with the small dot of Venus onto a piece of paper, SkyCenter Director Alan Strauss re-creates the first historic recording of a Venus transit made in 1639. (Photo: Patrick McArdle/UANews)

The crowd is watching as Adam Block, astrophotographer and astronomy educator with the UA’s Mt. Lemmon SkyCenter, is about to repeat Horrocks’ famous experiment. Block sets up a paper screen in the path of a pencil-thin beam of light streaming through a hole in the observatory wall.

“Obviously, Horrocks couldn’t look at the sun directly through his telescope without risking blindness,” Block says. “By using a sheet of paper, not only was he able to observe safely, but also use a pencil to trace what he saw.”

Today, we no longer have to rely on pencil and paper, of course, to witness the transit of Venus, an event that won’t happen again until 2117, past the lifetime of pretty much everyone alive.

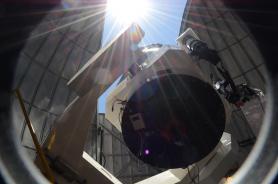

At the SkyCenter’s main observatory, home of the 32-inch Schulman Telescope, the largest telescope dedicated solely to public viewing, visitors of the Venus transit event hosted by the SkyCenter were treated to spectacular views.

Atop the tallest mountain in Southern Arizona, the tiny dot of Venus surrounded by the giant, orange glowing sun as viewed with a hand-held solar filter and the naked eye just before both – star and planet – slipped behind the mountains rising above the valley west of Tucson.

Adam Block positions the telescopes for viewing Venus passing across the sun. (Photo: Patrick McArdle/UANews)

To view the transit, Block had fitted a special filter in front of two small telescopes mounted onto the side of the massive Schulman instrument, whose opening was wrapped in reflective foil for protection.

“If we pointed the 32-inch telescope at the sun, the eyepiece would melt,” Block says. “Instead, we’re using a smaller telescope with a hydrogen alpha filter, revealing intricate details of the sun’s outer atmosphere as well as sun spots, filaments and other features caused by the star’s magnetic field.”

Through an attached camera, viewers watch a small segment of the sun’s flickering disk on a large flat screen display. At 3 p.m., only minutes before the predicted time of transit, Venus still remains unseen, shrouded in the black void of space surrounding the bright, roiling disk of light.

Outside the observatory, under a cloudless sky and a mild breeze, Martin Hamar is sitting in a camping chair, adjusting the mount of his amateur telescope. A digital SLR camera, attached to the eyepiece, clicks every minute.

“I expose one image per minute,” Hamar explains. “For us here on the mountain, the transit will be observable for 259 minutes, so that’s 259 photos. I’m hoping to stitch them all together and make an 8-second time lapse video of Venus crossing the sun.”

The 32-inch Schulman Telescope at the UA SkyCenter is the largest telescope dedicated exclusively to public viewing. (Photo: Patrick McArdle/UANews)

Hamar, a 76-year old “former retiree” who got his first telescope at age 9 and now runs his own company, has traveled from Connecticut to Tucson to get an unimpeded view of the event.

“During the last Venus transit in 2004, it was cloudy on the East Coast. I got one picture when the clouds parted for a moment, but that was it,” he says. “This time I decided not to put up with the lousy weather over there and come here instead. But I just talked to friends back home who said it’s actually clear and they’re having a great view.”

Hamar says he practiced with his equipment for two months in anticipation of the Venus transit to make sure everything would work as he hoped.

“I’m sure glad I did,” he says with a grin. “Everything is working out magnificently.”

Inside the dome, Block looks up from his computer screen where he controls the settings and position of the telescopes.

“OK, we’re getting close, people. Venus should appear within the next minute or so. Watch for a small dent to appear in the Sun’s disk at a position of about 1 o’clock.”

Visitors at the UA's SkyCenter watch as the black disk of Venus makes first contact with the sun during the June 5 transit of Venus. (Photo: Patrick McArdle/UANews)

And there it is. Barely perceptible at first against the quivering edge of the sun, the black background appears to be pushing in against the edge in the area Block predicted, like a drop of liquid touching the wall of a vessel. Minutes later, the tiny disk of Venus materializes out of the black, seemingly putting a dent into the bright disk of light.

Block is excited about the image on the screen. “Few humans have seen this, so I hope you’re all enjoying it.”

Transits of Venus are very rare events because the planet’s orbit is tilted relative to the Earth’s. Only four times every 243 years do the planets line up with the sun for the spectacle to occur.

The transits following Horrocks’ first observation, in 1761 and 1769, sparked a frenzy of scientific discovery. Hundreds of expeditions were staged, sending ships with observers around the world.

At the time, astronomers were still trying to figure out exactly how big the solar system was and by putting observers in positions spaced far enough apart, they could use geometry to calculate the distance between the Earth, Venus and the sun, and ultimately gauge the size of the universe.

The Earth, it was calculated from the flurry of crude observations at various points and times around the world, was much farther away from the sun than expected: about 100 million miles. The actual distance, we now know, is about 93 million miles.

Amateur astronomer Martin Hamar developed a method to use his iPad to align his telescope with the Sun. "At night, it's easy because you have Polaris, the North Star, but during the daytime, it's much more difficult," he said. (Photo: Daniel Stolte/UANews)

Today, transits are used by planet hunters to look for exoplanets, planets orbiting stars other than the sun. Detecting the infinitesimally small, but measureable dip in brightness that occurs when a planet crosses the face of a star in line with a telescope on Earth or in space, astronomers gather clues about which stars could harbor planets.

“If aliens looking for planets outside of their solar system were observing the Venus transit, they’d know that there is at least one planet circling around the Sun,” Block explains.

While astronomers on Earth have their eyes and cameras on the sun, in an orbit high above Earth’s atmosphere, the Hubble Space Telescope slowly turns until it faces in exactly the opposite direction.

Hubble, too, it turns out, is repeating Horrocks’ famous observing experiment, except that in place of a sheet of paper, it uses the moon’s surface.

“The idea is to record that tiny dip in brightness that results when Venus obscures a tiny fraction of the sun,” Block explains. “Invisible to us, the moon will shine just a fraction less brightly when it happens.”

By the time Venus’ black dot appeared on the sheet of paper Horrocks has been staring at for hours, the young astronomer was ecstatic. He wrote: “Contemplate, I repeat, this most extraordinary phenomenon, never in our time to be seen again! The planet Venus, drawn from her seclusion, modestly delineating on the sun, without disguise…”

Too poor to afford a visit to a friend living in a village 30 miles away who had also observed the transit, Horrocks died suddenly two years after his historic observation.

– By Daniel Stolte

*Source: The University of Arizona