ANN ARBOR, Mich.— The ideal of equal housing opportunities is closer to becoming a reality in most major U.S. metro areas, according to a University of Michigan researcher.

“While black-white segregation remains high in many places, there are reasons to be optimistic that ‘apartheid’ no longer aptly describes much of urban America,” said Reynolds Farley, an investigator at the U-M Institute for Social Research (ISR) who studies racial segregation in the United States.

According to Farley, residential segregation is a lens to assess whether the U.S. has achieved the equality symbolized by the 2008 Presidential election, when the Obama family moved into 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue.

“Where you live determines much about what happens to your family, including where your children go to school, how easily you can access healthcare—and the quality of that care, your exposure to crime, the quality of your municipal services, your local tax rates, your access to fresh, healthy food, and whether your home appreciates or declines in value,” said Farley, who has a special interest in the City of Detroit and maintains a website about the history and future of the Motor City.

Based on a wide range of evidence, including studies of his own and work by Brown University researchers, Farley says that black-white segregation is decreasing in the country’s largest cities. “Even Chicago and Detroit, which were bastions of racial segregation, have become more integrated,” Farley said. “And in all 394 U.S. metro areas studied, black-white segregation has declined steadily from 1980 to 2010.”

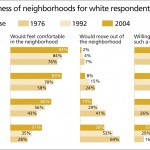

In 1976, 1992, and again in 2004, Farley and colleagues conducted studies in metro Detroit to try to identify the causes of the persistently high levels of segregation in that area. Using a variety of survey approaches, the researchers tried to determine whether white residents felt comfortable with blacks living on their block, and whether they would remain if blacks moved onto their block.

The racial attitudes of white Detroiters shifted substantially during that time, the researchers found. In 1976, about 75 percent said they would be comfortable if their neighborhood had one black family. By 2004, about 93 percent said they would be comfortable with a black neighbor. Still, if the racial composition of their neighborhoods was 50-50, about half of white respondents said they would be uncomfortable in 2004.

Nevertheless, Farley says that the changes in white people’s attitudes about moving away when African Americans move into a neighborhood offer strong evidence that the era of white flight is over. In 1976, 40 percent of whites said they would try to move away if their neighborhood composition became one-third black. But nearly 30 years later, 19 percent said they would try to leave.

The increase in residential integration within households is also contributing to these changes in attitudes about neighborhood integration, Farley said. “Black-white marriages are no longer rare,” he said, “and the mixed-race population is growing rapidly.

“Many of the structures that created and maintained the American Apartheid system have been greatly weakened or removed. As a result, the long trend toward lower levels of black-white segregation seems sure to continue.”

Farley’s article on racial segregation trends appears in the current issue of Contexts, a publication of the American Sociological Association.

*Source: University of Michigan