Surprising new study finds that the mantle is hotter than we thought

The temperature of Earth’s interior affects everything from the movement of tectonic plates to the formation of the planet.

A new study led by Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) suggests the mantle—the mostly solid, rocky part of Earth’s interior that lies between its super-heated core and its outer crustal layer – may be hotter than previously believed. The new finding, published March 3 in the journal Science, could change how scientists think about many issues in Earth science including how ocean basins form.

“At mid-ocean ridges, the tectonic plates that form the seafloor gradually spread apart,” said the study’s lead author Emily Sarafian, a graduate student in the MIT-WHOI Joint Program. “Rock from the upper mantle slowly rises to fill the void between the plates, melting as the pressure decreases, then cooling and re-solidifying to form new crust along the ocean bottom. We wanted to be able to model this process, so we needed to know the temperature at which rising mantle rock starts to melt.”

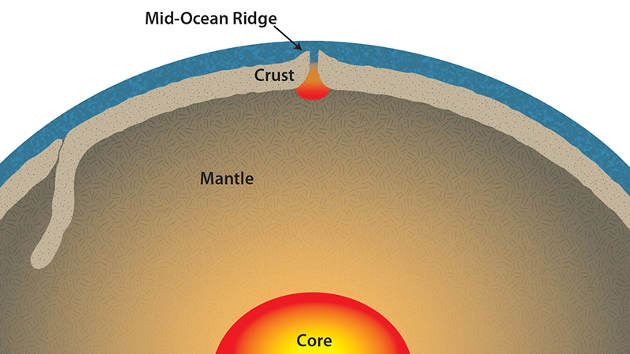

Earth’s mantle is the mostly solid, rocky interior of our planet. At mid-ocean ridges, the tectonic plates that form the sea floor gradually spread apart. Rock from the upper mantle slowly rises to fill that void, melting as the pressure decreases, then cooling and re-solidifying as new crust along the seafloor. To be able to model this process, scientists needed to know the temperature at which rising mantle rock starts to melt. (Illustration by Jack Cook, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

But determining that temperature isn’t easy. Since it’s not possible to measure the mantle’s temperature directly, geologists have to estimate it through laboratory experiments that simulate the high pressures and temperatures inside the Earth.

Water is a critical component of the equation: the more water (or hydrogen) in rock, the lower the temperature at which it will melt. The peridotite rock that makes up the upper mantle is known to contain a small amount of water. “But we don’t know specifically how the addition of water changes this melting point,” said Sarafian’s advisor, WHOI geochemist Glenn Gaetani. “So there’s still a lot of uncertainty.”

Study lead author Emily Sarafian is a graduate student in the MIT-WHOI Joint Program. In her work, Sarafian combines two very different approaches to geological research: experimental petrology and magnetotellurics—an ability that led her to her current discovery. (Photo by Jayne Doucette, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

To figure out how the water content of mantle rock affects its melting point, Sarafian conducted a series of lab experiments using a piston-cylinder apparatus , a machine that uses electrical current, heavy metal plates, and stacks of pistons in order to magnify force to recreate the high temperatures and pressures found deep inside the Earth. Following standard experimental methodology, Sarafian created a synthetic mantle sample. She used a known, standardized mineral composition and dried it out in an oven to remove as much water as possible.

Until now, in experiments like these, scientists studying the composition of rocks have had to assume their starting material was completely dry, because the mineral grains they’re working with are too small to analyze for water. After running their experiments, they correct their experimentally determined melting point to account for the amount of water known to be in the mantle rock.

“The problem is, the starting materials are powders, and they adsorb atmospheric water,” Sarafian said. “So, whether you added water or not, there’s water in your experiment.”

Sarafian took a different approach. She modified her starting sample by adding spheres of a mineral called olivine, which occurs naturally in the mantle. The spheres were still tiny—about 300 micrometers in diameter, or the size of fine sand grains—but they were large enough for Sarafian to analyze their water content using secondary ion mass spectrometry (SIMS). From there, she was able to calculate the water content of her entire starting sample. To her surprise, she found it contained approximately the same amount of water known to be in the mantle.

Based on her results, Sarafian concluded that mantle melting had to be starting at a shallower depth under the seafloor than previously expected.

To verify her results, Sarafian turned magnetotellurics – a technique that analyzes the electrical conductivity of the crust and mantle under the seafloor. Molten rock conducts electricity much more than solid rock, and using magnetotelluric data, geophysicists can produce an image showing where melting is occurring in the mantle.

But a magnetotelluric analysis published in Nature in 2013 by researchers at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in San Diego showed that mantle rock was melting at a deeper depth under the sea floor than Sarafian’s experimental data had suggested.

At first, Sarafian’s experimental results and the magnetotelluric observations seemed to conflict, but she knew both had to be correct. Reconciling the temperatures and pressures Sarafian measured in her experiments with the melting depth from the Scripps study led her to a startling conclusion: “The oceanic upper mantle must be 60°C (~110°F) hotter than current estimates,” Sarafian said.

A 60-degree increase may not sound like a lot compared to a molten mantle temperature of more than 1,400°C. But Sarafian and Gaetani say the result is significant. For example, a hotter mantle would be more fluid, helping to explain the movement of rigid tectonic plates.

Funding for this research was provided by the National Science Foundation and the WHOI Deep Ocean Exploration Institute.

*Source: Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution