Protecting key regions that comprise just 17 percent of Earth’s land may help preserve more than two-thirds of its plant species, according to a new study by an international team of scientists, including a biologist from North Carolina State University.

The researchers from Duke University, NC State and Microsoft Research used computer algorithms to identify the smallest set of regions worldwide that could contain the largest numbers of plant species. They published their findings in the journal Science.

“Our analysis shows that two of the most ambitious goals set forth by the 2010 Convention on Biological Diversity – to protect 60 percent of Earth’s plant species and 17 percent of its land surface – can be achieved, with one major caveat,” said Stuart L. Pimm, Doris Duke Professor of Conservation Ecology at Duke’s Nicholas School of the Environment and the corresponding author on the paper.

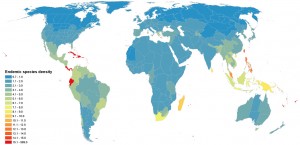

Red sections have more endemic species density. Image credit: North Carolina State University (Click image to enlarge)

“To achieve these goals, we need to protect more land, on average, than we currently do, and much more in key places such as Madagascar, New Guinea and Ecuador. Our study identifies regions of importance. The logical – and very challenging – next step will be to make tactical local decisions within those regions to secure the most critical land for conservation.”

Plant species aren’t haphazardly distributed across the planet. Certain areas, including Central America, the Caribbean, the Northern Andes, and regions in Africa and Asia, have much higher concentrations of endemic species, that is, those which are found nowhere else.

“Species endemic to small geographical ranges are at a much higher risk of being threatened or endangered than those with large ranges. We combined regions to maximize the numbers of species in the minimal area. With that information, we can more accurately evaluate each region’s relative importance for conservation, and assess international priorities accordingly,” explained Lucas N. Joppa, a conservation scientist at Microsoft’s Computational Science Laboratory in Cambridge, U.K., and the paper’s lead author.

To identify which of Earth’s regions contain the highest concentrations of endemic species, relative to their geographic size, the researchers analyzed data on more than 100,000 different species of flowering plants, compiled by the Royal Botanic Gardens in Kew, England.

Joppa and Piero Visconti, also of Microsoft’s Computational Science Laboratory, created and ran the complex algorithms needed to analyze the large spatial database.

Based on their computations, Clinton N. Jenkins, a research scholar at NC State, created a color-coded global map identifying high-priority regions for plant conservation, ranked by endemic species density.

“We also mapped where the greatest numbers of small-ranged birds, mammals and amphibians occur, and found that they are broadly in the same places we show to be priorities for plants,” Jenkins said. “So preserving these lands for plants will benefit many animals, too.”

Without having access to the Royal Botanic Gardens’ plant database, which is one of the largest biodiversity databases in the world, the team would not have been able to conduct the analysis, Joppa noted.

Pimm and Jenkins lead the conservation nonprofit Saving Species, which works with local communities and international agencies to purchase and protect threatened lands that are critical for biodiversity.

“The fraction of land being protected in high-priority regions increases each year as new national parks are established and greater autonomy is given back to indigenous peoples to allow them to manage their traditional lands,” Pimm said. “We’re getting tantalizingly close to achieving the Convention of Biological Diversity’s global goals. But the last few steps remaining are huge ones.”

*Source: North Carolina State University