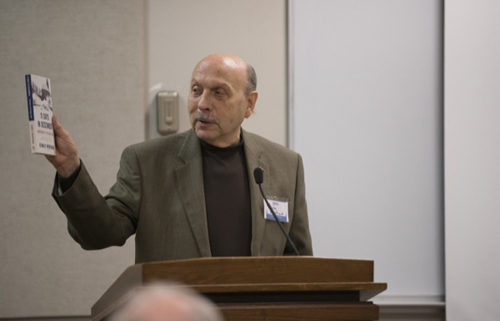

Author discusses World War I Christmas truce at UDARF luncheon

An unbelievable thing happened during the first holiday season of World War I — peace broke out.

How the killing stopped for a few days in northern France and Flanders was the topic of a talk given by Stanley Weintraub, the author of Silent Night: The Story of the World War I Christmas Truce (Free Press 2002), during a University of Delaware Association of Retired Faculty luncheon held Tuesday, Dec. 4, in Clayton Hall.

Weintraub, the Evan Pugh Professor Emeritus of Arts and Humanities at Penn State University, has written numerous histories and biographies, including Long Day’s Journey Into War: Pearl Harbor and a World at War-December 7, 1941 (Dutton Adult, 1991).

“I was working on a book about the armistice at the end of World War I (A Stillness Heard Around the World, Oxford Press, USA, 1987), about the last week of World War I, when I came across a book about an impromptu Christmas truce during the first year of the war, 1914,” Weintraub said. “Most people thought it was just a fable.”

A while later, Weintraub was put in touch with a British Broadcasting Company producer who had done a radio series with veterans of World War I.

“He said that while I could not use all of the materials that he had gathered, I was welcome to look at them,” Weintraub said. “He said he also had material about the Christmas truce.”

Weintraub and his wife Rodelle, author of Fabian Feminist: Bernard Shaw and Woman (Pennsylvania University Press, 1977) spent the next several summers at the British Library newspaper archive at Colindale and the Imperial War Museum, both in London, perusing letters to the editor and records of the British Army companies who were at the front during that long ago Christmas.

Author Stanley Weintraub discussed his book about the World War I Christmas truce during a meeting of the University of Delaware Association of Retired Faculty. Photo by Kathy F. Atkinson

“The troops had been fighting since August 1914 and they were tired,” Weintraub said. “It was now December, the cold rains and some snow had come and the trenches were full of mud and water. Nobody wanted to fight.”

While individual military members have never had the power to stop a war, some of the combatants facing each other across that no man’s land between 300 miles of trenches decided to celebrate Christmas as best they could.

German soldiers, closer to home than the British forces, had traditional tabletop Christmas trees trucked to the front, placing the candle-trimmed holiday icons atop the parapets above the trenches, Weintraub said.

“The British were intensely curious about what was going on,” Weintraub said. “They crawled out of their trenches and met the Germans in the 100-yard-wide stretch of no man’s land between the lines. They talked about Christmas and peace.”

Another popular topic for discussion was the idea of a football (soccer) match, a seemingly impossible goal as the deadly piece of real estate was filled with shell holes and the bodies of the dead of wounded.

The idea persisted and the wounded were removed and clergy from both forces presided over mass burials for fallen soldiers.

The combatants also decided to exchange holiday gifts.

“The British had Christmas boxes, with plum puddings and canned items, while the Germans brought boxes filled with cigars and sausages,” Weintraub said. “The men also got to sample beer from barrels rolled in from Germany.”

There was also a spirited Christmas carol competition with a German tenor from the Berlin Opera singing Silent Night. The French countered with a Paris Opera tenor performing Cantique de Noël (O Holy Night).

“It’s hard to imagine all of this going on between the trenches, but it did,” Weintraub said. “They actually filled in the shell holes, and in many cases played soccer, with improvised rules.”

Weintraub said the British soldiers were so floored by what happened — no shooting, and quiet, almost like the war had ended — that they sent letters to their parents, wives or girlfriends, who in turn sent these to the English newspapers as letters to the editors.

“The British government was furious about this,” Weintraub said. “You had to hate your enemy, and how could you hate him when you traded gifts with him, visited his trenches and sat under his Christmas tree.”

Of course, the truce couldn’t last. Soldiers from the front were pulled and troops from the reserve rear areas that had not participated in the Christmas truce were moved to the front.

“In some cases, the truce lasted until New Year’s Day but the camaraderie gradually drifted away and the armies fought again,” Weintraub said. “No attempt was made for a truce during the next three Christmases, and the war finally ended on Nov. 11 (in 1918), more than a month before Christmas.”

While no definitive list of casualties can be cited, the number of combatants killed in the World War I is estimated to be between 7-10 million. Called the “war to end all wars” by then U.S. President Woodrow Wilson, the conflict also took the lives of 7 million civilians.

As for the soccer matches, the Germans won most of them.

– Article by Jerry Rhodes

*Source: University of Delaware