Microbe mobilizes ‘iron shield’ to block arsenic uptake in rice

University of Delaware researchers have discovered a soil microbe that mobilizes an “iron shield” to block the uptake of toxic arsenic in rice.

Arsenic occurs naturally in rocks and soils, air and water, plants and animals. It’s used in a variety of industrial products and practices, from wood preservatives, pesticides and fertilizers, to copper smelting. Chronic exposure to arsenic has been linked to cancer, heart disease and diabetes.

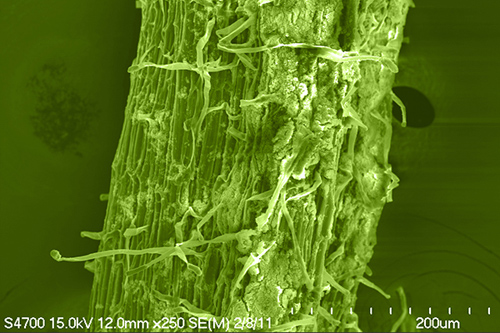

Clumps of bacteria (soil microbe EA106) and iron plaque begin forming on the roots of a rice plant. This “iron shield” blunts the uptake of arsenic. Image by Venkatachalam Lakshmanan and Deepak Shantharaj taken with the scanning electron microscope (SEM), UD Bioimaging Center.

The UD finding gives hope that a natural, low-cost solution — a probiotic for rice plants — may be in sight to protect this global food source from accumulating harmful levels of one of the deadliest poisons on the planet. Rice currently is a staple in the diet of more than half the world’s population.

Harsh Bais, associate professor of plant and soil sciences, led the UD team that conducted the study, which is reported in the international journal Planta. The work was supported by the National Science Foundation. His co-authors include professors Angelia Seyfferth and Janine Sherrier and postdoctoral researchers Venkatachalam Lakshmanan, Gang Li and Deepak Shantharaj, all in the Department of Plant and Soil Sciences.

Plant and soil scientists at the University of Delaware are studying the effectiveness of the soil microbe EA106 in decreasing the uptake of arsenic in rice plants. From right, assistant professor Angelia Seyfferth, associate professor Harsh Bais, who also is the lead investigator of the study, postdoctoral researcher Venkatachalam Lakshmanan and professor Janine Sherrier. Photo of researchers by Lindsay Yeager

The soil microbe the team identified is named “EA106” for UD alumna Emily Alff, who isolated the strain when she was a graduate student in Bais’ lab. The microbe was found among the roots of a North American variety of rice grown commercially in California. It belongs to a group of gram-negative, rod-shaped bacteria called the Pantoea, which form yellowish mucus-like colonies.

Because rice is grown underwater — often in water contaminated with arsenic in such hot spots as Bangladesh, India and China — it takes in 10 times more arsenic than do other cereal grains, such as wheat and oats.

As rice plants absorb phosphate, a nutrient needed for growth, they also take up arsenic, which has a similar chemical structure.

“This particular microbe, EA106, is good at mobilizing iron, which competes with the arsenic, effectively blocking arsenic’s pathway,” Bais explains. “An iron plaque forms on the surface of the roots that does not allow arsenic to go up into the rice plant.”

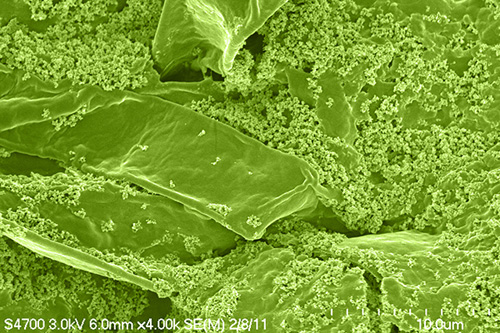

The dust-like coating on this rice root is a combination of EA106 soil microbes and the iron plaque the microbes mobilize. In University of Delaware research, this “iron shield” has shown to decrease the uptake of arsenic into rice plants. Image by Venkatachalam Lakshmanan and Deepak Shantharaj taken with the scanning electron microscope (SEM), UD Bioimaging Center.

The researchers conducted the study with hundreds of rice plants — some grown in soil, others grown hydroponically — in UD’s Fischer Greenhouse. Inoculations with EA106 improved the uptake of iron at the plant roots, while reducing the accumulation of toxic arsenic in the plant shoots.

While the results are promising, Bais says the next steps in the research will determine if a natural solution to this serious issue is at hand.

“We’re not all the way to the grain level yet. We are working on that now, to see if EA106 prevents arsenic accumulation in the grain. That is the ultimate test,” Bais says.

Highly magnified view of the clumps of EA106 soil microbes and the iron plaque on a rice root. Image by Venkatachalam Lakshmanan and Deepak Shantharaj taken with the scanning electron microscope (SEM), UD Bioimaging Center.

If the next phase of the research shows success, Bais says inexpensive technologies (think even a cement mixer) exist for coating rice seeds with beneficial bacteria.

He also sees an added plus — fortifying rice plants with iron would not only reduce arsenic, but also increase the grain’s iron content as a nutritional benefit.

“I grew up very near to a rice field in India, so I have a different interest in this problem,” Bais says. “Basically, these small farmers don’t have much to feed their families. They grow rice on small plots of land with soil and water contaminated with arsenic, a poison. The work we are doing is important for them, and to the global security of rice.”

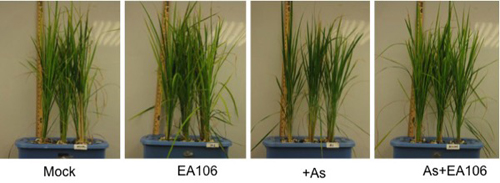

UD experiments demonstrated the impact of rice plants that have had root inoculations with the soil microbe EA106. From left, the “mock” or control plants were not treated with EA106 or with arsenic. Plants treated with EA106 show robust growth, while plants treated with arsenic (+As) are stunted and have some yellow leaves. At far right, rice plants treated with arsenic rebound when their roots are inoculated with EA106.

In related research, Bais wants to assess the performance of plants inoculated with EA106 when they face multiple stresses, from both arsenic and from rice blast, a fungus that kills an estimated 30 percent of the world’s rice crop each year.

Bais’ group previously isolated a natural bacterium from rice paddy soil that blunts the rice blast fungus. His group is evaluating how a natural alliance between benign microbes and rice can strengthen the plant’s disease resistance.

Both plant threats face rice farmers near his parents’ home in India. Bais plans to start field tests there when he visits with family this summer.

“The whole world is waking up to biologicals,” Bais says. “It’s an exciting time for researchers in this area.”

– Article by Tracey Bryant

*Source: University of Delaware