Some thirty million years ago, Ganges river dolphins diverged from other toothed whales, making them one of the oldest species of aquatic mammals that use echolocation, or biosonar, to navigate and find food. This also makes them ideal subjects for scientists working to understand the evolution of echolocation among toothed whales.

New research, led by Frants Havmand Jensen, a Danish Council for Independent Research | Natural Sciences postdoctoral fellow at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, shows that freshwater dolphins produce echolocation signals at very low sound intensities compared to marine dolphins, and that Ganges river dolphins echolocate at surprisingly low sound frequencies. The study, “Clicking in shallow rivers,” was published in the journal PLOS ONE.

“Ganges River dolphins are one of the most ancient evolutionary branches of toothed whales,” says Jensen. “We believe our findings help explain the differences in echolocation between freshwater and marine dolphins. Our findings imply that the sound intensity and frequency of Ganges river dolphin may have been closer to the ‘starting point‘ from which marine dolphins gradually evolved their high-frequent, powerful biosonar.”

A rare sight of the fast and shy Ganges river dolphin. (Photo by Rubaiyat Mansur, Whale and Dolphin Conservation Society)

The scientists believe these differences evolved due to differences in freshwater and marine environments and the location and distribution of prey in those environments.

A complex, underwater environment

To sustain themselves, river dolphins must find their food, often small fish or crustaceans, in highly turbid water where visibility seldom exceeds a few inches. Like their marine relatives, they manage this using echolocation: They continuously emit sound pulses into the environment and listen for the faint echoes reflected off obstacles while paying special attention to the small details in the echoes that might signify a possible meal.

The environment that freshwater dolphins operate in poses very different challenges to a biosonar than the vast expanses of the sea where most dolphins later evolved. “Dolphins that range through the open ocean often feed on patchily distributed prey, such as schools of fish,” Jensen says. “They have had a large advantage from evolving an intense biosonar that would help them detect prey over long distances, but we have little idea of how the complex river habitats of freshwater dolphins shape their biosonar signals.”

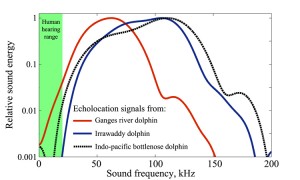

Toothed whales echolocate using ultrasonic signals — at frequencies too high for humans to hear. A new study led by WHOI postdoctoral fellow Frants Jensen found that the Ganges river dolphin produces sounds at a surprisingly low frequency compared to species of dolphins. This figure charts the energy distribution as a function of frequency for echolocation clicks used by three species of toothed whales: the Ganges river dolphin (not a member of the dolphin family, but rather the very old Platanistidae family), the Irrawaddy dolphin, a freshwater dolphin that ranges into coastal areas, and the Bottlenose dolphin, a marine dolphin. The relative sound energy has been “normalized” so the chart displays the same maximum sound energy production for each species. All three species include signal energy at low frequency, but the members of the dolphin family (the Irrawaddy and Bottlenose dolphin) include signal energy at much higher frequency as well. Graph courtesy of Frants Havmand Jensen, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (Click image to enlarge)

Shy study animals with a surprisingly deep voice

To answer that question, the researchers recorded the echolocation signals of two species of toothed whales inhabiting the same mangrove forest in the southern part of Bangladesh: The Ganges river dolphin, an exclusively riverine species that is actually not part of the dolphin family but rather the Platanistidae family, and the Irrawaddy, a freshwater toothed whale from the dolphin family that lives in both coastal and riverine habitats.

Surprisingly, the echolocation signals turned out to be much less intense than those employed by marine dolphins of similar size and it seemed that the freshwater dolphins were looking for prey at much shorter distances. From this, the researchers surmise that both the dolphin species and the river dolphin were echolocating at short range due to the complex and circuitous river system that they were foraging in.

While both Irawaddy and Ganges river dolphin produced lower intensity biosonar, the Ganges river dolphin had an unexpectedly low frequency biosonar, nearly half as high as expected if this species had been a marine dolphin.

”It is very surprising to see these animals produce such low-frequent biosonar sounds. We are talking about a small toothed whale the size of a porpoise producing sounds that would be more typical for a killer whale or a large pilot whale,” says Professor Peter Teglberg Madsen from Aarhus University in Denmark, an expert on toothed whale biosonar and co-author of the study.

A new perspective on the evolution of biosonar

The study suggests that echolocation in toothed whales initially evolved as a short, broadband and low-frequent click. As dolphins and other toothed whales evolved in the open ocean, the need to detect schools of fish or other prey items quickly favored a long-distance biosonar system. As animals gradually evolved to produce and to hear higher sound frequencies, the biosonar beam became more focused and the toothed whales were able to detect prey further away.

However, the Ganges river dolphin separated from other toothed whales early throughout this evolutionary process, adapting to a life in shallow, winding river systems where a high-frequency, long-distance sonar system may have been less important than other factors such as high maneuverability or the flexible neck that helps these animals capture prey at close range or hiding within mangrove roots or similar obstructions.

Improved tools for counting animals

Freshwater dolphins are among the most endangered animal species. Only around a thousand Ganges river dolphins are thought to remain, and they inhabit some of the most polluted and overfished river systems on Earth. The results of this study will help provide local collaborators with a new tool in their struggle to conserve these highly threatened freshwater cetaceans. Using acoustic monitoring devices to identify the local species may help researchers estimate how many animals remain, and to identify what areas are most important to them.

Dr. Frants Havmand Jensen is funded by an Individual Postdoctoral Fellowship and a Sapere Aude award from the Danish Council for Independent Research | Natural Sciences.

*Source: Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution