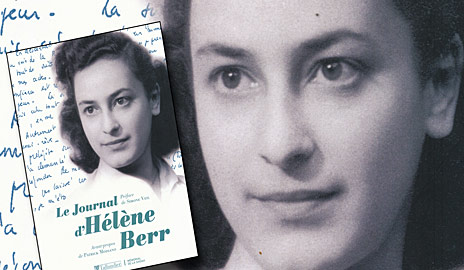

The story of Hélène Berr, a young French Jewish woman who chronicled her life in Paris during the German occupation and died in a concentration camp, had a certain poignancy for Yale senior Zoe Egelman.

A New Yorker, Egelman shares with Berr the experience of growing up in a world capital with a long-established Jewish population. Just as Berr was when she began to record her journal in 1942, Egelman is a 21 year old completing her studies in the literature of a foreign language at a prestigious university. Berr, a student in the English studies department at the Sorbonne, was doing her master’s thesis on John Keats; Egelman, a French major at Yale who has studied literature at the Sorbonne, is doing her senior thesis on Berr.

First published in 2008, Berr’s diary quickly earned the young writer the title “the French Anne Frank.” (Ironically, notes Egelman, both Frank and Berr died in Bergen-Belsen within weeks of each other; Berr just days before the camp’s liberation). While Berr’s literary gifts have been acknowledged by critics and readers after the journal’s publication, the diary had yet to attract much scholarly attention when Egelman chose it as her thesis topic.

To get a fuller understanding of Berr, her family, and the times she documented, Egelman applied for a Salo W. and Jeannette M. Baron Research Grant offered by the Yale Program for the Study of Antisemitism to travel to Paris.

Describing the diary as “a poetic masterpiece of a young student of letters as well as an immense contribution to social history,” the Yale student pledged in her grant application to use the “unique archival resources [in Paris] to fill in the historical and biographical context of Hélène’s personal narrative.” She also wrote that she would literally trace Hélène’s well-documented footsteps across Paris.

Egelman did indeed follow Berr’s path right up to the doorstep of the family’s home in the fashionable 7th arrondissement, a few steps from the city’s most iconic landmark, the Eiffel Tower. Seeing such tangible evidence of the family’s “haute-bourgeois” (upper-middle-class) existence, says Egelman, helped her understand how assimilated and largely secularized Jews like the Berrs, whose family had deep roots in France, might have felt themselves exempt from the fate of Jews who had arrived more recently in the nation.

In April 1942, almost two years after the Germans marched into Paris, Berr — still living in the family home — started to describe her daily life in the French capital. According to Egelman, the journal that Berr kept for almost two years is a chronicle of an ever-more restricted existence, as the Nazis stepped up their program of denying Jews their rights, their jobs, their access to public facilities, their property, and, finally, their lives.

When Berr started to keep the diary, she could travel freely — even making excursions to the family’s country home. She met regularly with classmates and friends, played the violin, and intended to earn a doctorate and some day become a professor of English. In the first entry of the diary, she describes going to the home of the poet Paul Valéry to pick up a book he had inscribed to her.

She also writes of her new love interest: a young man named Jean Morawiecki. Berr’s reflections on their relationship figure prominently in her diary, and it is Morawiecki who is ultimately responsible for the journal’s survival.

As the vise of Nazism tightens around her, and even after her three siblings all escaped the country, Berr continued to document the ever-bleaker news of deportations and escalating brutality. Forbidden from taking her qualifying exams at the Sorbonne, and then from attending classes, Berr threw herself into working for the UGIF, a Jewish agency that looked after the welfare of Jewish children whose parents had already been deported. During the time she volunteered there, she became involved in the effort to smuggle these children to safety.

Finally facing the inevitability of her situation, Berr entrusted her journal to a non-Jewish family servant, with instructions, in case of her death, to give it to Morawiecki, who had already fled the country to join the Free French in North Africa.

On the eve of being deported and having just heard an eyewitness account of the carnage in the camps, she wrote the last entry in her diary: “Horror! Horror! Horror!” The words occur in Joseph Conrad’s “Heart of Darkness,” and in Shakespeare’s “Macbeth,” notes Egelman. Even though Berr was reading both, Egelman believes that Shakespeare is the more likely source of the diarist’s last recorded words.

After the war, the Berr family’s chef who kept the journal returned it to Hélène’s brother Jacques, who passed it on to Morawiecki. The latter held onto it for 50 years, until Hélène’s niece Mariette Job traced it to him. It would be another 14 years before the journal would be published by the Shoah Memorial Museum, and it has since been been published in more than two dozen countries.

Egelman’s thesis will look at Berr’s literary development in the course of the journal, focusing especially on the young woman’s affinity for the poet Keats.

As a footnote, Egelman recounts the coincidence that a short time ago she decided to listen to a testimony from the Fortunoff archives. “It had nothing really to do with my thesis,” she says. ”I just wanted to take advantage of a great resource at Yale that I had never used before.” She chose as her first testimony that of a woman, Fanny, who was born in Paris the same year as Hélène. From a very different family background, and having joined the Resistance in Lyon in 1942, Fanny in all probability would never have met Hélène. In her testimony, however, she recounts that after she was arrested in 1944 and was being deported to Auschwitz she found herself in a convoy with children who had taken refuge in the “foyers d’enfants” of the UGIF, where Hélène had volunteered. “It’s possible,” reflects Egelman, “that these were children Hélène had tried to save from the same fate that she herself would suffer.”

– By Dorie Baker

*Source: Yale University