An international team of scientists led by groups from the Max Planck Institute of Quantum Optics (MPQ) in Garching, Germany, and from the U.S. Department of Energy’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and the University of California at Berkeley has used ultrashort flashes of laser light to directly observe the movement of an atom’s outer electrons for the first time.

Through a process called attosecond absorption spectroscopy, researchers were able to time the oscillations between simultaneously produced quantum states of valence electrons with great precision. These oscillations drive electron motion. “With a simple system of krypton atoms, we demonstrated, for the first time, that we can measure transient absorption dynamics with attosecond pulses,” says Stephen Leone of Berkeley Lab’s Chemical Sciences Division, who is also a professor of chemistry and physics at UC Berkeley. “This revealed details of a type of electronic motion – coherent superposition – that can control properties in many systems.”

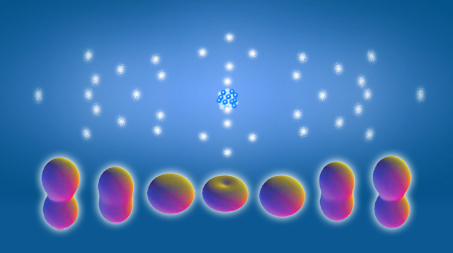

About the image: A classical diagram of a krypton atom (background) shows its 36 electrons arranged in shells. Researchers have measured oscillations of quantum states (foreground) in the outer orbitals of an ionized krypton atom, oscillations that drive electron motion. Image credit: Berkeley Lab.

Leone cites recent work by the Graham Fleming group at Berkeley on the crucial role of coherent dynamics in photosynthesis as an example of its importance, noting that “the method developed by our team for exploring coherent dynamics has never before been available to researchers. It’s truly general and can be applied to attosecond electronic dynamics problems in the physics and chemistry of liquids, solids, biological systems, everything.”

The team’s demonstration of attosecond absorption spectroscopy began by first ionizing krypton atoms, removing one or more outer valence electrons with pulses of near-infrared laser light that were typically measured on timescales of a few femtoseconds (a femtosecond is 10^-15 second, a quadrillionth of a second). Then, with far shorter pulses of extreme ultraviolet light on the 100-attosecond timescale (an attosecond is 10^-18 second, a quintillionth of a second), they were able to precisely measure the effects on the valence electron orbitals.

The results of the pioneering measurements performed at MPQ by the Leone and Krausz groups and their colleagues are reported in the August 5 issue of the journal Nature.

Parsing the fine points of valence electron motion

Valence electrons control how atoms bond with other atoms to form molecules or crystal structures, and how these bonds break and reform during chemical reactions. Changes in molecular structures occur on the scale of many femtoseconds and have often been observed with femtosecond spectroscopy, in which both Leone and Krausz are pioneers.

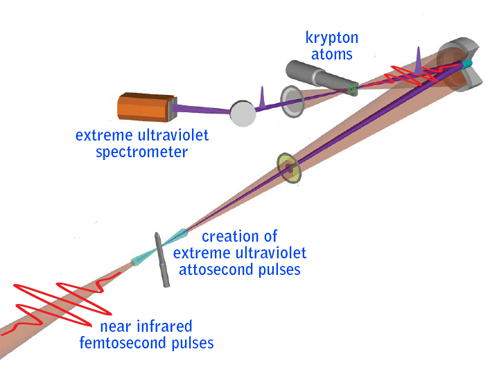

About the image: Femtosecond-scale pulses were fired to ionize krypton atoms (wide beam). Separately created attosecond-scale pulses (narrow beam) were absorbed by the krypton atoms. Spectroscopy mapped the precise timing of the oscillation between quantum states thus created. Image credit: Berkeley Lab.

Zhi-Heng Loh of Leone’s group at Berkeley Lab and UC Berkeley worked with Eleftherios Goulielmakis of Krausz’s group to perform the experiments at MPQ. By firing a femtosecond pulse of infrared laser light through a chamber filled with krypton gas, atoms in the path of the beam were ionized by the loss of one to three valence electrons from their outermost shells.

The experimenters separately generated extreme-ultraviolet attosecond pulses (using the technique called “high harmonic generation”) and sent the beam of attosecond probe pulses through the krypton gas on the same path as the near-infrared pump pulses.

By varying the time delay between the pump pulse and the probe pulse, the researchers found that subsequent states of increasing ionization were being produced at regular intervals, which turned out to be approximately equal to the time for a half cycle of the pump pulse. (The pulse is only a few cycles long; the time from crest to crest is a full cycle, and from crest to trough is a half cycle.)

“The femtosecond pulse produces a strong electromagnetic field, and ionization takes place with every half cycle of the pulse,” Leone says. “Therefore little bursts of ions are coming out every half cycle.”Although expected from theory, these isolated bursts were not resolved in the experiment. The attosecond pulses, however, could precisely measure the production of the ionization, because ionization – the removal of one or more electrons – leaves gaps or “holes,” unfilled orbitals that the ultrashort pulses can probe.

The attosecond pulses do so by exciting electrons from lower energy orbitals to fill the gap in krypton’s outermost orbital – a direct result of the absorption of the transient attosecond pulses by the atoms. After the “long” femtosecond pump pulse liberates an electron from the outermost orbital (designated 4p), the short probe pulse boosts an electron from an inner orbital (designated 3d), leaving behind a hole in that orbital while sensing the dynamics of the outermost orbital.

In singly charged krypton ions, two electronic states are formed. A wave-packet of electronic motion is observed between these two states, indicating that the ionization process forms the two states in what’s known as quantum coherence.

About the image: In krypton’s single ionization state, quantum oscillations in the valence shell cycled in a little over six femtoseconds. Attosecond pulses probed the details (black dots), filling the gap in the outer orbital with an electron from an inner orbital, and sensing the changing degrees of coherence between the two quantum states thus formed (below). Image credit: Berkeley Lab.

Says Leone, “There is a continual ‘orbital flopping’ between the two states, which interfere with each other. A high degree of interference is called coherence.” Thus when the attosecond probe pulse clocks the outer valence orbitals, it is really clocking the high degree of coherence in the orbital motion caused by ionization.

Indispensable attosecond pulses

“When the bursts of ions are made quickly enough, with just a few cycles of the ionization pulse, we observe a high degree of coherence,” Leone says. “Theoretically, however, with longer ionization pulses the production of the ions gets out of phase with the period of the electron wave-packet motion, as our work showed.”

So after just a few cycles of the pump pulse, the coherence is washed out. Thus, says Leone, “Without very short, attosecond-scale probe pulses, we could not have measured the degree of coherence that resulted from ionization.”

The physical demonstration of attosecond transient absorption by the combined efforts of the Leone and Krausz groups and their colleagues will, in Leone’s words, “allow us to unravel processes within and among atoms, molecules, and crystals on the electronic timescale” – processes that previously could only be hinted at with studies on the comparatively languorous femtosecond timescale.

“Real-time observation of valence electron motion,” by Eleftherios Goulielmakis, Zhi-Heng Loh, Adrian Wirth, Robin Santra, Nina Rohringer, Vladislav Yakovlev, Sergey Zherebtsov, Thomas Pfeifer, Abdallah Azzeer, Matthias Kling, Stephen Leone, and Ferenc Krausz, appears in the 5 August 2010 issue of the journal Nature.

This work was supported by the Max Planck Society, King Saud University, and the Munich Center for Advanced Photonics. Stephen Leone’s group is supported by the Air Force Office of Scientific Research, the National Science Foundation, and U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science.

Theoretical modeling was led by Robin Santra, who is supported by DOE’s Office of Science.

The post is written by – Paul Preuss

*Source: Berkeley Lab