Yale neurologist Steven Novella populates his podcasts and blogs with aliens, ghosts and creationists for a single purpose: to help resurrect the lost art of scientific thinking.

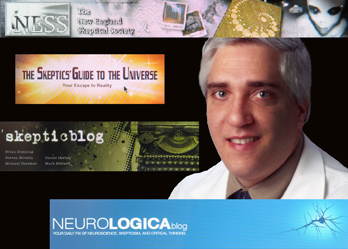

“I am interested in how otherwise intelligent people can get things so horribly wrong,” says Novella. In the process of answering that question he created the website Skeptics Guide to the Universe — which, with 150,000 listeners a week, is one of the 10 most popular science sites on the internet.

Novella, an expert in neuromuscular function, has learned what people like. Given a choice between an essay on logical fallacies or a casual conversation about haunted houses or UFO sightings, he knows which one most people would choose.

Seven years ago, he wrote a print column on scientific education for a non-profit group and had a loyal 200 subscribers. His podcasts on topics such as cell phones and cancer or intelligent design attract that many listeners in an hour.

“Print can be pretty dense; with audio you have somebody in your head and there is a certain intimacy that you don’t have with the written word,” Novella says. “But it has to be entertaining.”

His message, however, is serious, focusing on how an inability to understand scientific thinking infects public discourse on many subjects. Why, he asks, do people believe the earth was created 10,000 years ago, or that vaccines cause autism despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary?

“I espouse scientific skepticism that deals with the demarcation line between science and pseudoscience,” Novella says. “We have a lot of amateur scientists who thought they were doing science but were getting things absolutely wrong.”

He has created a variety of formats to describe common errors that lead almost all of us astray.

He explores many of these fallacies on his blogs Neurologica and the New England Skeptical Society, which he co-founded, as well as in contributions to other sites (https://skepticblog.org).

For instance on UFOs, Novella concedes the existence of interesting and even at times unexplained phenomena. However, strange phenomena do not necessarily prove the existence of aliens, he asserts.

“This is the ‘where there is smoke there is fire’ argument. But I think it misses an important question — there may be fire (a phenomenon) but what kind of fire? I think the fire is a multifaceted psycho-cultural phenomenon,” he says.

Novella also enlists psychology to explain why even very smart people come up with erroneous conclusions when they stray from rigors of sound scientific practices. One of the chief traps is called “confirmation bias,” the tendency to seek information that bolsters your views and ignore data that contradicts those views.

“This is one of the hardest fallacies to overcome,” he says.

There are plenty of other logical fallacies that throw us off track, he says. We also regularly confuse correlation with causation – incorrectly inferring that event A caused event B because one happened before the other. This fallacy is at the heart of the vaccine and autism controversy, he says, noting that just because B happened after A, it does not follow that A caused B.

The inability to detect these fallacies can be deadly when it comes to our health, so Novellas started the blog Science-Based Medicine. The public needs to be skeptical of medical claims that are not based on carefully controlled research studies, he says.

“The scientifically illiterate risk throwing away time, money and emotions invested in false hopes,” Novella asserts.

The human brain makes these errors as a matter of course, and it takes time and effort to avoid them, asserts the Yale scientist, but as the public struggles to understand complex societal problems, the skill is crucial.

“We are products of evolution and if we don’t recognize these pitfalls we will make the same cognitive errors over and over again,” he says. “We live in a democracy and with that comes the responsibility to analyze and act upon huge amounts of information, but we haven’t been given the tools to make those decisions.”

This article is written by: Bill Hathaway

*Source: Yale University.