Charles Johnson, University of Washington professor emeritus of English and award-winning author, has released a new book of short stories, his fourth.

The dozen stories in “Night Hawks,” published this month by Scribner, range from realism to light science fiction, myth and his own personal experiences, laced gently with humor and philosophy. Calling him a “modern master,” Kirkus Reviews wrote of the new book: “Johnson’s stories can be as morally instructive as fables, as fancifully ingenious as Twilight Zone scripts, and as elegantly inscrutable as Zen riddles.”

Johnson, the S. Wilson and Grace M. Pollock Endowed Professor of Writing, is author of 23 books over a five-decade career and the recipient of numerous awards, including the 1990 National Book Award for his novel “Middle Passage.”

He talked with UW News about the new book and his creative process for short story-writing.

Where do the initial ideas — the very first thought — for stories generally come from? Is there any pattern?

C.J.: Eleven of the 12 stories in “Night Hawks” were written for Humanities Washington’s yearly Bedtime Stories fundraiser. I fathered this reading series 20 years ago with the suggestion that the board members at Humanities Washington give a theme or prompt to three writers who would then use it to create a new literary work for the event.

I’ve done this 19 times now. Each year now the talented musicians in the Bushwick Book Club create a song for the stories, which they perform after the writer reads it. Over the last two decades themes we’ve been given to write to — which all involve bedtime or nighttime in some way — include “night hawks,” “night watch,” and “pillow talk.” Writing to a theme this way has blessed me to dream up a new story I would never have thought of doing on my own.

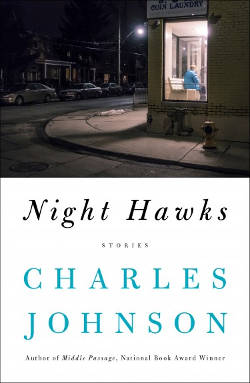

Prof. Charles Johnson’s fourth book of stories, “Night Hawks,” was published by Scribner. Image credit: University of Washington

This is reminiscent of improvisational comedy, where performers create a piece from words suggested by the audience. What theme, if you can say, suggested your lead story, “The Weave,” which was included in the prestigious 2016 Pushcart Anthology?

There is a similarity with the Bedtime Stories approach and improvisational comedy. Or even with medieval troubadours called upon to whip up a story requested by an audience. For “The Weave,” I believe the prompt or phrase for that year was “red eye.” In the third sentence of the story it says of the character Ieesha, “She has a sore throat and red eyes…”

What do you learn about a story by reading it aloud before an audience?

I never just “read” a story. I dramatically perform it. One composes a story as one would, say, a musical composition. There are places where the tempo speeds up, other places where it slows down. Places where one turns up the volume when reading, and other places where one lowers it. You discover these places when you read the story aloud.

I always select, for example, a passage from a novel or story and test it, play and experiment with performing it before I give readings. That means there are chapters and passages I can’t just read “cold” because I haven’t had the opportunity to feel my way through them, as an actor would.

As a practicing Buddhist, I can also say that control of one’s breath is also important during the reading experience. One also changes, if possible, voices when reading dialogue because each character speaks or sounds differently from the others. Before giving a reading (or even a lecture), I always sit first in meditation to prepare myself for delivering the performance.

How do you know when an idea will become a story? What elements need to be in place for you to think: Yes, I can write this.

In my essay “Storytelling and the Alpha Narrative” in “The Way of the Writer: Reflections on the Art and Craft of Storytelling” (2016) I explain this process. We begin with a conflict, what writer John Barth once called the “ground situation.” That’s your first good idea at the start of the story. You then need a second good idea for the middle of the story, one that expands, develops or complicates in some way the first idea. And then at the story’s end you need a third good idea to wrap things up. Using this model, then, one needs three good ideas for storytelling.

How much of a story do you have to have planned out before you begin? Do characters sometimes take you in unexpected directions?

Ninety percent of good writing is rewriting and/or re-envisioning the story as one carefully moves through it, layering and cutting each sentence and paragraph until one achieves specificity or granularity of detail, rhythm and music in the prose. As the writer discovers new details for character and event, it is very likely that one’s original idea will be modified and an early outline will have to be abandoned; a writer gets to know his or her characters better with each new detail that despoils possibilities.

That’s the joy of literary art — this process of discovery that makes the challenge of every story different.

During your final edits of a piece of fiction, are you more likely to take something out or put something in?

Because I highly value poetic compression in my prose, I’m most likely to take something out if it doesn’t contribute to the music of a sentence.

With writing as with cartooning — which you also do — it’s good to know when to stop, when enough lines are laid down. How do you know when a story is done?

I know a story is done when I can’t add another line (or word) to it without disturbing the delicate balance of music and meaning, sound and sense that comes from relentless revisions as it moved from one draft to another.

Finally, a new book such as “Night Hawks” is complete, jacketed and in your hands. What tend to be your thoughts?

I feel a profound sense of relief. The stories were written over 12 years. It always takes a team of talented people — my editor, proofreaders, the publisher, and many others — to bring any book to its final form as a gift to readers, and for their crucial help I am eternally grateful.

By Peter Kelley

*Source: University of Washington