Using bacteria as bait, UA scientists caught wild ocean viruses and found that the genetic lines between virus types in nature are less blurred than previously thought.

A fishing expedition of microscopic proportions led by University of Arizona ecologists revealed that the lines between virus types in nature are less blurred than previously thought.

Using lab-cultured bacteria as “bait,” a team of scientists led by Matthew Sullivan has sequenced complete and partial genomes of about 10 million viruses from an ocean water sample in a single experiment.

J. Cesar Ignacio Espinoza, a UA doctoral student in Sullivan’s lab and co-first author on the Nature paper, in a mobile lab set up on a research cruise to sample viruses in the ocean. (Photo credit: Sullivan lab)

The study, published online Monday by the journal Nature, revealed that the genomes of viruses in natural ecosystems fall into more distinct categories than previously thought. This enables scientists to recognize actual populations of viruses in nature for the first time.

“You could count the number of viruses from a soil or water sample in a microscope, but you would have no idea what hosts they infect or what their genomes were like,” said Sullivan, an associate professor in the UA’s Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, an assistant professor in the Department of Soil, Water and Environmental Science in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences and member of the UA’s BIO5 Institute. “Our new approach for the first time links those same viruses to their host cells. In doing so, we gain access to viral genomes in a way that opens up a window into the roles these viruses play in nature.”

Li Deng, co-first author on the Nature paper, stands on the deck of the research vessel “Western Flyer” in front of the sampling device used to measure salinity, temperature and depth of the ocean during sample collection. (Photo credit: Sullivan lab)

Sullivan’s team developed a new approach called viral tagging, which uses cultivated bacterial hosts as “bait” to fish for viruses that infect that host. The scientists then isolate the DNA of those viruses and decipher their sequence.

“Instead of a continuum, we found at least 17 distinct types of viruses in a single sample of Pacific Ocean seawater, including several that are new to science – all associated with the single ‘bait’ host used in the experiment,” Sullivan said.

The research lays the groundwork for a genome-based system of identifying virus populations, which is fundamental for studying the ecology and evolution of viruses in nature.

“Before our study, the prevailing view was that the genome sequences of viruses in a given environment or ecosystem formed a continuum,” Sullivan said. “In other words, the lines between different types of viruses appeared blurred, which prevented scientists who wanted to assess the diversity of viruses in the wild from recognizing and counting distinct types of viruses when they sampled for them.”

“Microbes are now recognized as drivers of the biogeochemical engines that fuel Earth, and the viruses that infect them control these processes by transferring genes between microbes, killing them in great numbers and reprogramming their metabolisms,” explained the first author of the study, Li Deng, a former postdoctoral researcher in Sullivan’s lab who now is a research scientist at the Helmholtz Research Center for Environmental Health in Neuherberg, Germany. “Our study for the first time provides the methodology needed to match viruses to their host microbes at scales relevant to nature.”

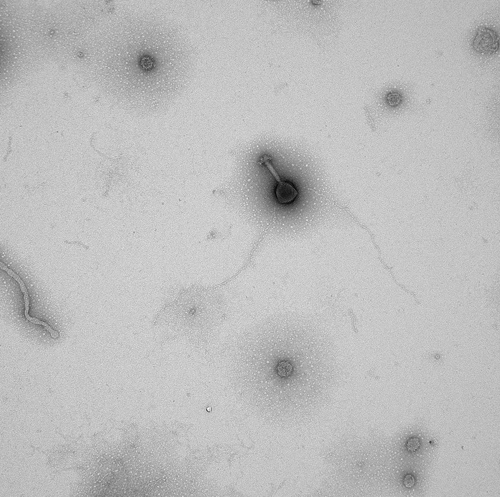

Electron microscopy image of a virus sample collected during a research cruise with the “Western Flyer” off the coast of Monterey Bay, California. (Photo credit: Sullivan lab)

Getting a grip on the diversity of viruses infecting a particular host is critical beyond environmental sciences, Deng said, and has implications for understanding how viruses affect pathogens that cause human disease, which in turn is relevant for vaccine design and antiviral drug therapy.

Sullivan estimates that up to 99 percent of microbes that populate the oceans and drive global processes such as nutrient cycles and climate have not yet been cultivated in the lab, which makes their viruses similarly inaccessible.

“For the first time we can count virus types,” he explained, “and we can ask questions like, ‘Which virus is more abundant in one environment than another?’ Further, the genomic data gives us a way to infer what a virus might do to its bacterial host.”

Mobile lab setup inside the “Western Flyer” for processing and filtering water collected at sea to capture viruses. (Photo credit: Li Deng)

The study benefited from collaboration with Joshua Weitz, an associate professor and theoretical ecologist from the Georgia Institute of Technology who spent time as a visiting researcher in the Sullivan lab.

The new data help scientists like Weitz develop new concepts and theories about how viruses and bacteria interact in nature.

“This new method provides incredibly novel sequence data on viruses linked to a particular host,” Weitz explained. “The work is foundational for developing a means to count genome-based populations that serve as starting material for predictive models of how viruses interact with their host microbes. We can now map viral populations with their genomes, providing information about who they are and what they do.”

The study, “Viral tagging reveals discrete populations in Synechococcus viral genome sequence space,” was co-first authored by Cesar Ignacio-Espinoza, a doctoral candidate in molecular and cellular biology; Ann Gregory, a doctoral candidate in soil, water and environmental sciences; and Bonnie Poulos, assistant research scientist in cecology and evolutionary biology. In addition to Weitz, co-authors not at the UA include Georgia and Philip Hugenholtz of the Australian Centre for Ecogenomics at the University of Queensland in Brisbane, Australia.

The U.S. Department of Energy, the UA’s Biosphere 2 and BIO5 Institute, the National Science Foundation, the Burroughs Wellcome Fund and the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation funded the study.

– By Daniel Stolte

*Source: The University of Arizona (Published on July 14, 2014)