*New analytical method approaches the unstudied 99% of the human genome*

WASHINGTON, D.C., – 02 Nov 2011: Evolutionary history shows that human populations likely originated in Africa, and the Genographic Project, the most extensive survey of human population genetic data to date, suggests where they went next. A study by the Project finds that modern humans migrated out of Africa via a southern route through Arabia, rather than a northern route by way of Egypt. These findings will be highlighted today at a conference at the National Geographic Society.

National Geographic and IBM’s Genographic Project scientific consortium have developed a new analytical method that traces the relationship between genetic sequences from patterns of recombination – the process by which molecules of DNA are broken up and recombine to form new pairs. Ninety-nine percent of the human genome goes through this shuffling process as DNA is being transmitted from one generation to the next. These genomic regions have been largely unexplored to understand the history of human migration.

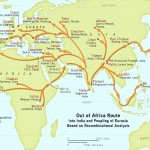

Through a new analytical method, IBM and the Genographic Project find new evidence to support a southern route of human migration from Africa via the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait in Arabia before any movement heading north, and suggest a special role for south Asia in the “out of Africa” expansion of modern humans. Image credit: IBM

By looking at similarities in patterns of DNA recombination that have been passed on and in disparate populations, Genographic scientists confirm that African populations are the most diverse on Earth, and that the diversity of lineages outside of Africa is a subset of that found on the continent. The divergence of a common genetic history between populations showed that Eurasian groups were more similar to populations from southern India, than they were to those in Africa. This supports a southern route of migration from Africa via the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait in Arabia before any movement heading north, and suggests a special role for south Asia in the “out of Africa” expansion of modern humans.

Ajay Royyuru, senior manager at IBM’s Computational Biology Center, said: “Over the past six years, we’ve had the opportunity to gather and analyze genetic data around the world at a scale and level of detail that has never been done before. When we started, our goal was to bring science expeditions into the modern era to further a deeper understanding of human roots and diversity. With evidence that the genetic diversity in southern India is closer to Africa than that of Europe, this suggests that other fields of research such as archaeology and anthropology should look for additional evidence on the migration route of early humans to further explore this theory.”

The new analytical method looks at recombinations of DNA chromosomes over time, which is one determinant of how new gene sequences are created in subsequent generations. Imagine a recombining chromosome as a deck of cards. When a pair of chromosomes is shuffled together, it creates combinations of DNA. This recombination process occurs through the generations.

Recombination contributes to genome diversity in 99% of the human genome. However, many believed it was impossible to map the recombinational history of DNA due to the complex, overlapping patterns created in every generation. Now, by applying detailed computational methods and powerful algorithms, scientists can provide new evidence on the size and history of ancient populations.

IBM researcher Laxmi Parida, who defined the new computational approach in a study published in Molecular Biology and Evolution, said: “Almost 99% of the genetic makeup of an individual are layers of genetic imprints of the individual’s many lineages. Our challenge was whether it was even feasible to tease apart these lineages to understand the commonalities. Through a determined approach of analytics and mathematical modeling, we undertook the intricate task of reconstructing the genetic history of a population. In doing so, we now have the tools to explore much more of the human genome.”

The Genographic Project continues to fill in the gaps of our knowledge of the history of humankind and unlock information from our genetic roots that not only impacts our personal stories, but can reveal new dimensions of civilizations, cultures and societies over the past tens of thousands of years.

“The application of new analytical methods, such as this study of recombinational diversity, highlights the strength of the Genographic Project’s approach. Having assembled a tremendous resource in the form of our global sample collection and standardized database, we can begin to apply new methods of genetic analysis to provide greater insights into the migratory history of our species,” said Genographic Project Director Spencer Wells.

The recombination study highlights the initial six-year effort by the Genographic Project to create the most comprehensive survey of human genetic variation using DNA contributed by indigenous peoples and members of the general public, in order to map how the Earth was populated. Nearly 500,000 individuals have participated in the Project with field research conducted by 11 regional centers to advance the science and understanding of migratory genealogy. This database is one of the largest collections of human population genetic information ever assembled and serves as an unprecedented resource for geneticists, historians and anthropologists.

Background: The Genographic Project seeks to chart new knowledge about the migratory history of the human species and answer age-old questions surrounding the genetic diversity of humanity. The project is a nonprofit, multi-year, global research partnership of National Geographic and IBM with field support by the Waitt Family Foundation. At the core of the project is a global consortium of 11 regional scientific teams following an ethical and scientific framework and who are responsible for sample collection and analysis in their respective regions. The Project is open to members of the public to participate through purchasing a public participation kit from the Genographic Web site (www.nationalgeographic.com/genographic), where they can also choose to donate their genetic results to the expanding database. Sales of the kits help fund research and support a Legacy Fund for indigenous and traditional peoples’ community-led language revitalization and cultural projects.

About IBM Research

IBM Research is the world’s largest information technology research organization, with about 3,000 scientists and engineers at nine labs across the world. For more information about IBM Research, visit www.research.ibm.com.

*Source: IBM