New graduate’s medical research experience inspires her

When Hira Peracha came to the University of Delaware as a first-year student, she knew she wanted to go on to medical school, but she was unsure of the path that would take her there or what specialty she might eventually pursue.

She had certainly never heard of mucopolysaccharidosis or its acronym, MPS, and had never met anyone with one of the rare, genetic and often fatal MPS disorders.

Today, Peracha is a new UD graduate, who has already started medical school after spending part of the summer continuing the research she began three years ago as a sophomore.

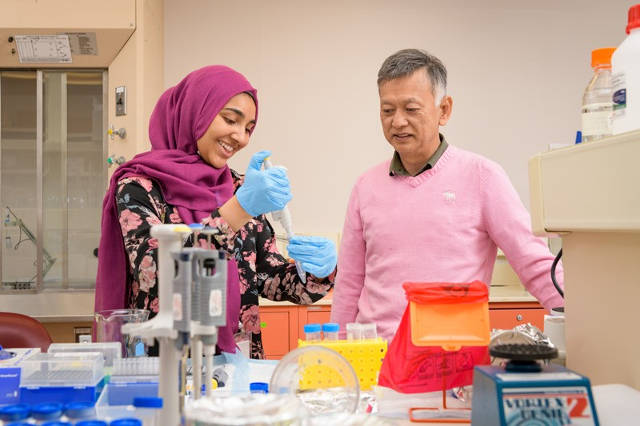

Hira Peracha (left) works in the research lab where her mentor, Dr. Shunji Tomatsu of Nemours/Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children, studies the rare genetic disorders known as MPS. Photo by Evan Krape

That research has focused on MPS, a group of enzyme disorders in which the body is unable to break down long chains of sugar molecules. Those molecules build up in cells, tissue and organs and cause health problems that can range in type and severity.

One in 25,000 babies is estimated to be born with MPS, but symptoms don’t generally appear for a year or two and, even then, the condition can be difficult to diagnose. As the disorders progress, they can cause problems with the skeleton and joints, short stature, and heart, breathing and neurological abnormalities.

Peracha is the author of four published papers on MPS, has attended and presented at international conferences on the subject and has conducted her research with one of the world’s most prominent MPS specialists, Dr. Shunji Tomatsu, at Nemours/Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children in Wilmington, Delaware.

In late July, Peracha assisted at a conference at the hospital that drew about 120 participants. Families from all over the world attended to learn about the latest research that might help their children with Morquio Syndrome, one of the seven identified types of MPS conditions.

“I came to UD as a neuroscience major who was pre-med, and I did undergraduate research as a Summer Scholar when I was a freshman,” Peracha said. “It was a great experience, but I decided I wasn’t that interested in the brain. So I changed my major to biological sciences, and I became fascinated by bones.”

Through the Delaware Centers of Biomedical Research Excellence (COBRE) program, she found Tomatsu, who is head of the Skeletal Dysplasia Research Lab at Nemours, where he specializes in MPS. An affiliated research mentor with UD’s Department of Biological Sciences, he regularly works with undergraduate students, encouraging them to delve into all aspects of research.

“Every year, I have one undergraduate and one graduate student from the University of Delaware,” Tomatsu said. “I encourage the undergraduates to write papers, not just to get an understanding of the disease but to really learn and know about it in depth.”

Although his lab and his research assistants are always productive, Peracha’s authorship of four papers has marked an unusual accomplishment for an undergraduate, he said.

Tomatsu’s lab has two major research projects underway, one to develop an MPS screening test for newborns and one to develop a gene therapy or enzyme therapy to treat Morquio Syndrome.

In her three years of work in the lab, Peracha did a variety of tasks and became increasingly interested in the effects of MPS on bones. She attended and made presentations at international conferences and met leading researchers. But, she said, it was the patients and their families that had the biggest impact on her.

“Nemours is a hub for MPS research and patient care, and patients come from all over the world,” she said. “When you meet them, instead of just seeing their medical records and their lab samples, then you really become passionate about this work.”

Peracha’s focus has been on the screening project, searching to identify biomarkers of the disease, since babies with MPS are born without obvious symptoms. An early diagnosis can mean earlier interventions to slow the effects of the disorder.

“Because it’s caused by a mutation in the genes, you could screen a newborn,” she said. “There’s no cure, but you can start a treatment plan as soon as you have a diagnosis.

“That’s what I’m trying to do — to find a way to screen before it’s too late.”

Peracha, who grew up in Middletown, Delaware, and commuted to UD from home, is uncertain if her future lies in work as a clinician or a researcher. Maybe, she said, she can find a way to combine the two, as Tomatsu has done.

She credited her parents with encouraging her to lead a meaningful life by finding a way to help others.

In addition to assistance from family and friends over the last four years, Peracha said, she received a great deal of support from UD faculty and programs. Advisers for her senior thesis were Tomatsu and UD faculty members Deni Galileo and Jessica Tanis, both in the Department of Biological Sciences, and Barbara Settles in the Department of Human Development and Family Science.

“I couldn’t have done this without all that help,” Peracha said.

Article by Ann Manser

*Source: University of Delaware