Hydraulic fracturing often brings up large volumes of water that need to be managed. A study led by The University of Texas at Austin has found that in the Permian Basin, a large oil field in Texas and New Mexico, reusing water at other well sites is a viable way to deal with the water that could also reduce potential instances of induced seismicity.

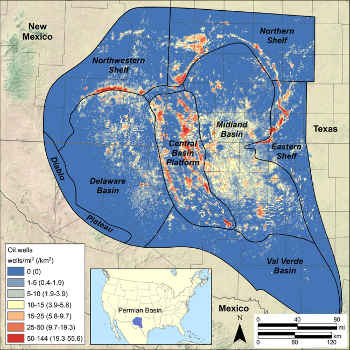

A map showing the Permian Basin and the distribution of oil wells in the region. Image credit: Bridget Scanlon/UT Austin

The UT Bureau of Economic Geology led the study that highlights key differences in water use between conventional drill sites and sites that use hydraulic fracturing, which is rapidly expanding in the Permian. The study was published in Environmental Science & Technology on Sept. 6, with results indicating that recycling water produced during operations at other hydraulic fracturing sites could help reduce potential problems associated with the technology. These include the need for large upfront water use and potentially induced seismicity or earthquakes, triggered by injecting the water produced during operations back into the ground.

“What I think may push the reuse of produced water a little more are concerns about over-pressuring and potential induced seismicity,” said lead author Bridget Scanlon, a senior research scientist and director of the bureau’s Sustainable Water Resources Program. “In the Permian we have a good opportunity for reusing or recycling produced water for hydraulic fracturing.”

Scanlon co-authored the study with bureau researchers Robert Reedy, Frank Male and Mark Walsh. The bureau is a research unit of the UT Jackson School of Geosciences.

Since the 1920s, the Permian Basin has been a very active area for conventional oil production, peaking in the 1970s and accounting for almost 20 percent of U.S. oil production. Hydraulic fracturing technology has revived production in that area by allowing companies to tap into immense oil reserves held in less permeable unconventional shale formations. The new technology is turning the conventional play into an unconventional play and has almost brought oil production up to the 1970s peak. The U.S. Geological Survey estimates that the Permian’s Wolfcamp Shale alone could hold 20 billion barrels of oil, the largest unconventional resource ever evaluated by the agency.

The study analyzed 10 years’ worth of water data from 2005 to 2015. The researchers tracked how much water was produced and how it was managed from conventional and unconventional wells and compared those volumes with water use for hydraulic fracturing.

Upfront, unconventional wells use much more water than conventional wells. The average volume of water needed per well has increased by about 10 times during the past decade, according to the study, with a median value of 250,000 barrels or 10 million gallons of water used per well in the Midland Basin in 2015. But unconventional wells produce much less water than conventional wells do, averaging about three barrels of water per barrel of oil versus 13 barrels of water per barrel of oil from conventional wells.

For conventional operations, the produced water is disposed of by injecting it into depleted conventional reservoirs, a process that maintains pressure in the reservoir and can help bring up additional oil through enhanced oil recovery. Unconventional wells generate only about a tenth of the water produced by conventional wells, but this “produced water” cannot be injected into the shales because of the low permeability of the shales. The study found that the produced water from unconventional wells is largely injected into non-oil-producing geologic formations—a practice that can increase pressure and could potentially result in induced seismicity or earthquakes.

The study points out that instead of injecting the produced water into these formations, operators could potentially reuse the water from unconventional wells to hydraulically fracture the next set of wells. Enough water is produced in the Midland and Delaware basins in the Permian to support hydraulic fracturing water use, and the water needs only minimal treatment (clean brine) to make it suitable for reuse.

Marc Engle, the chief of a U.S. Geological Survey program on water use associated with energy production, said that the study provides a comprehensive, data-driven look into how water is managed in the rapidly changing Permian Basin.

“This work by Scanlon et al., for the first time, provides interested stakeholders with a detailed view of water inflows and outflows from the Permian Basin,” said Engle. “Moreover, the work captures temporal trends through an important period where the industry shifted from vertical wells in conventional reservoirs to vertical then horizontal wells in continuous reservoirs.”

Although there is enough produced water for reuse, Scanlon said that infrastructure, questions about produced water ownership, and low cost of fresh or brackish groundwater may currently keep disposal practices as they are. But as unconventional operations in the Permian grow, reusing produced water may become more attractive.

The study was funded by the Cynthia and George Mitchell Foundation, the University of Texas Energy Institute, the Tight Oil Resource Assessment consortium and the Jackson School of Geosciences.

*Source: The University of Texas at Austin